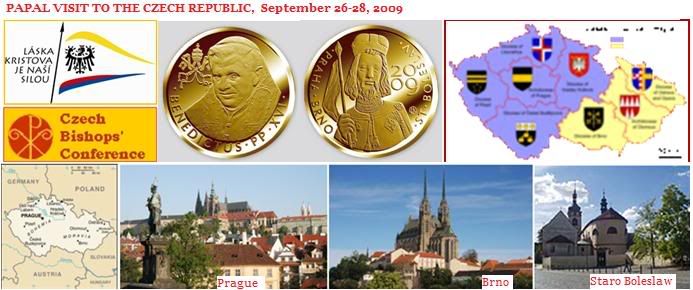

Day 2 - MEETING WITH ACADEMIC WORLD

Day 2 - MEETING WITH ACADEMIC WORLD

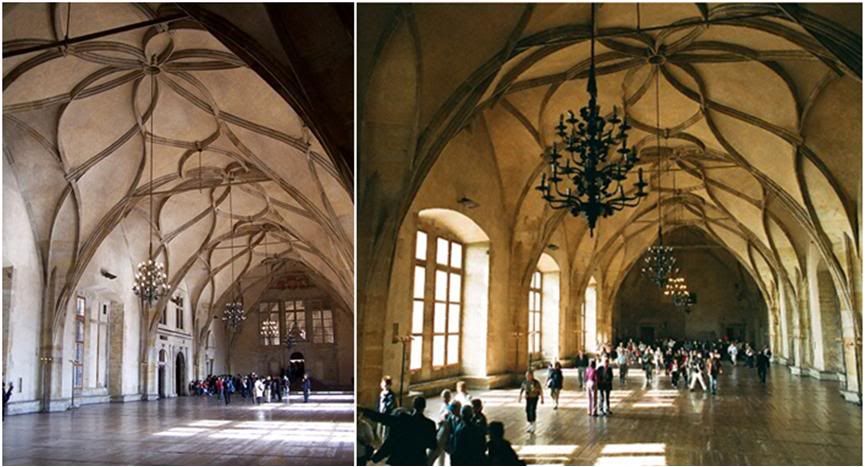

Vladislav Hall, Old Royal Palace

Prague Castle

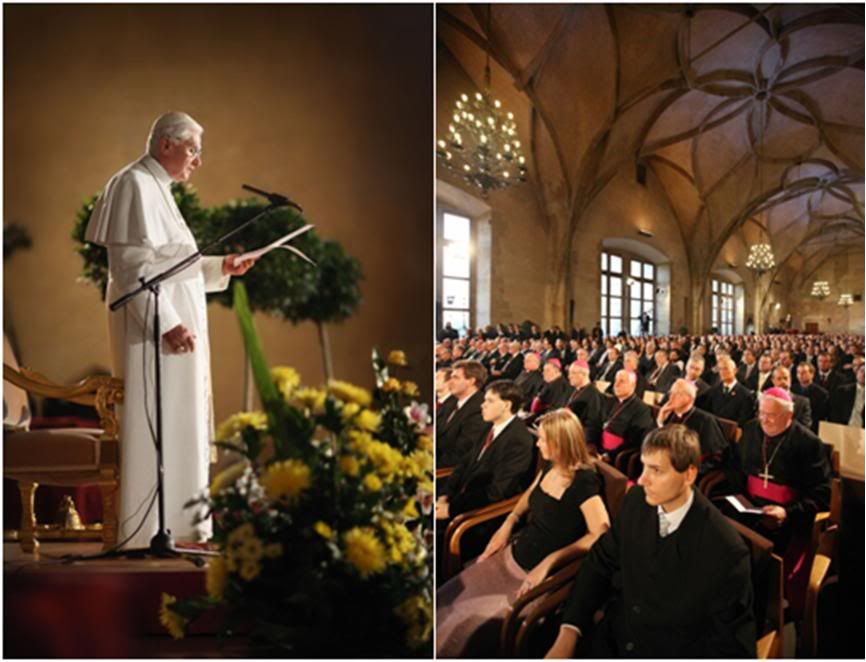

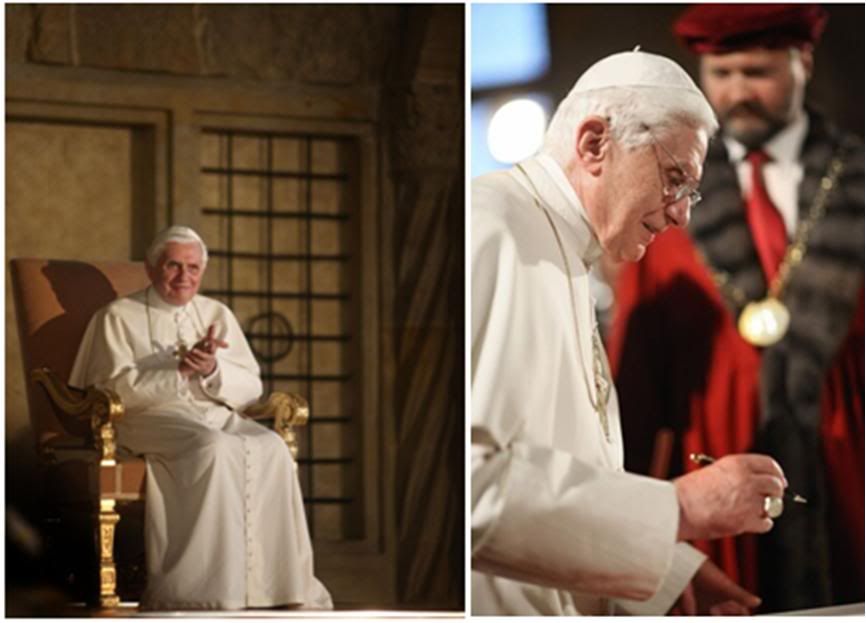

The Holy Father's final event for today was a meeting with the university world of the Czech Republic in the Vladislav Hall located in the Old Royal Palace in the Prague Castle complex.

(Since it was built in the last decade of the 15th century, this majestic hall has been used for most of the nation's important ceremonial events from, knights' tournaments in the Middle Ages to coronations, presidential elections and awarding of state decorations.)

Here is the text of the Pope's discourse to the academic world. It was delivered in English:

ADDRESS TO THE ACADEMIC WORLD

Vladislav Hall, Prague Castle

Mr President,

Distinguished Rectors and Professors,

Dear Students and Friends,

Our meeting this evening gives me a welcome opportunity to express my esteem for the indispensable role in society of universities and institutions of higher learning. I thank the student who has kindly greeted me in your name, the members of the university choir for their fine performance, and the distinguished Rector of Charles University, Professor Václav Hampl, for his thoughtful presentation.

The service of academia, upholding and contributing to the cultural and spiritual values of society, enriches the nation’s intellectual patrimony and strengthens the foundations of its future development.

The great changes which swept Czech society twenty years ago were precipitated not least by movements of reform which originated in university and student circles. That quest for freedom has continued to guide the work of scholars whose diakonia of truth is indispensable to any nation’s well-being.

I address you as one who has been a professor, solicitous of the right to academic freedom and the responsibility for the authentic use of reason, and is now the Pope who, in his role as Shepherd, is recognized as a voice for the ethical reasoning of humanity.

While some argue that the questions raised by religion, faith and ethics have no place within the purview of collective reason, that view is by no means axiomatic. The freedom that underlies the exercise of reason – be it in a university or in the Church – has a purpose: it is directed to the pursuit of truth, and as such gives expression to a tenet of Christianity which in fact gave rise to the university.

Indeed, man’s thirst for knowledge prompts every generation to broaden the concept of reason and to drink at the wellsprings of faith. It was precisely the rich heritage of classical wisdom, assimilated and placed at the service of the Gospel, which the first Christian missionaries brought to these lands and established as the basis of a spiritual and cultural unity which endures to this day.

The same spirit led my predecessor Pope Clement VI to establish the famed Charles University in 1347, which continues to make an important contribution to wider European academic, religious and cultural circles.

The proper autonomy of a university, or indeed any educational institution, finds meaning in its accountability to the authority of truth. Nevertheless, that autonomy can be thwarted in a variety of ways.

The great formative tradition, open to the transcendent, which stands at the base of universities across Europe, was in this land, and others, systematically subverted by the reductive ideology of materialism, the repression of religion and the suppression of the human spirit.

In 1989, however, the world witnessed in dramatic ways the overthrow of a failed totalitarian ideology and the triumph of the human spirit. The yearning for freedom and truth is inalienably part of our common humanity. It can never be eliminated; and, as history has shown, it is denied at humanity’s own peril.

It is to this yearning that religious faith, the various arts, philosophy, theology and other scientific disciplines, each with its own method, seek to respond, both on the level of disciplined reflection and on the level of a sound praxis.

Distinguished Rectors and Professors, together with your research there is a further essential aspect of the mission of the university in which you are engaged, namely the responsibility for enlightening the minds and hearts of the young men and women of today.

This grave duty is of course not new. From the time of Plato, education has been not merely the accumulation of knowledge or skills, but paideia, human formation in the treasures of an intellectual tradition directed to a virtuous life.

While the great universities springing up throughout Europe during the middle ages aimed with confidence at the ideal of a synthesis of all knowledge, it was always in the service of an authentic humanitas, the perfection of the individual within the unity of a well-ordered society.

And likewise today: once young people’s understanding of the fullness and unity of truth has been awakened, they relish the discovery that the question of what they can know opens up the vast adventure of how they ought to be and what they ought to do.

The idea of an integrated education, based on the unity of knowledge grounded in truth, must be regained. It serves to counteract the tendency, so evident in contemporary society, towards a fragmentation of knowledge.

With the massive growth in information and technology there comes the temptation to detach reason from the pursuit of truth. Sundered from the fundamental human orientation towards truth, however, reason begins to lose direction: it withers, either under the guise of modesty, resting content with the merely partial or provisional, or under the guise of certainty, insisting on capitulation to the demands of those who indiscriminately give equal value to practically everything.

The relativism that ensues provides a dense camouflage behind which new threats to the autonomy of academic institutions can lurk.

While the period of interference from political totalitarianism has passed, is it not the case that frequently, across the globe, the exercise of reason and academic research are – subtly and not so subtly – constrained to bow to the pressures of ideological interest groups and the lure of short-term utilitarian or pragmatic goals?

What will happen if our culture builds itself only on fashionable arguments, with little reference to a genuine historical intellectual tradition, or on the viewpoints that are most vociferously promoted and most heavily funded?

What will happen if in its anxiety to preserve a radical secularism, it detaches itself from its life-giving roots? Our societies will not become more reasonable or tolerant or adaptable but rather more brittle and less inclusive, and they will increasingly struggle to recognize what is true, noble and good.

Dear friends, I wish to encourage you in all that you do to meet the idealism and generosity of young people today not only with programmes of study which assist them to excel, but also by an experience of shared ideals and mutual support in the great enterprise of learning.

The skills of analysis and those required to generate a hypothesis, combined with the prudent art of discernment, offer an effective antidote to the attitudes of self-absorption, disengagement and even alienation which are sometimes found in our prosperous societies, and which can particularly affect the young.

In this context of an eminently humanistic vision of the mission of the university, I would like briefly to mention the mending of the breach between science and religion which was a central concern of my predecessor, Pope John Paul II.

He, as you know, promoted a fuller understanding of the relationship between faith and reason as the two wings by which the human spirit is lifted to the contemplation of truth (cf. Fides et Ratio, Proemium). Each supports the other and each has its own scope of action (cf. ibid., 17), yet still there are those who would detach one from the other.

Not only do the proponents of this positivistic exclusion of the divine from the universality of reason negate what is one of the most profound convictions of religious believers, they also thwart the very dialogue of cultures which they themselves propose.

An understanding of reason that is deaf to the divine and which relegates religions into the realm of subcultures, is incapable of entering into the dialogue of cultures that our world so urgently needs. In the end, “fidelity to man requires fidelity to the truth, which alone is the guarantee of freedom” (Caritas in Veritate, 9).

This confidence in the human ability to seek truth, to find truth and to live by the truth led to the foundation of the great European universities. Surely we must reaffirm this today in order to bring courage to the intellectual forces necessary for the development of a future of authentic human flourishing, a future truly worthy of man.

With these reflections, dear friends, I offer you my prayerful good wishes for your demanding work. I pray that it will always be inspired and directed by a human wisdom which genuinely seeks the truth which sets us free (cf. Jn 8:28). Upon you and your families I invoke God’s blessings of joy and peace

.

A professor-Pope wields

A professor-Pope wields

some rhetorical jujitsu

Sept. 27, 2009

PRAGUE - In the Japanese martial art of jiu-jitsu, the key to success is turning your opponent’s strength into a weakness. If your opponent is bigger or hits harder, you deflect his energy rather than directly opposing it, turning the blows back upon the guy delivering them.

In effect, Pope Benedict XVI has been practicing some rhetorical jiu-jitsu this weekend in the Czech Republic. Time and again, the pontiff has taken charges that secularists commonly level at Christianity and turned them back around – so that they become indictments of, rather than an apologia for, a secular worldview.

The Pope’s address this evening to a group of academics at Prague’s Charles University

[No, John! It was not at Charles University - it was at the Vladislaw Hall of the old Royal Palace] offered a classic case in point.

Secularists, for example, often accuse Christians of being dogmatists who are hostile to free, unfettered scientific thought. So, addressing an academic audience, Benedict XVI declared himself a former professor who remains “solicitous of the right to academic freedom.”

In fact, the Pope argued, the very university in which the meeting took place was actually founded by the Catholic Church, and was shaped by the “rich heritage of classical wisdom” which the Church nurtured over long centuries.

Academic freedom, Benedict argued, lives up to this legacy only to the extent that it is in service to truth. Once intellectuals give up on the idea of truth, he warned, all that’s left is the naked will to power – and if you want a real hornet’s nest for academic freedom, there it is.

“Relativism … provides a dense camouflage behind which new threats to the autonomy of academic institutions can lurk,” the Pope said, speaking in English as he has throughout his trip.

“Is it not the case that frequently, across the globe, the exercise of reason and academic research are – subtly and not so subtly – constrained to bow to the pressures of ideological interest groups and the lure of short-term utilitarian or pragmatic goals?” the Pope asked.

“What will happen if our culture builds itself only on fashionable arguments, with little reference to a genuine historical intellectual tradition, or on the viewpoints that are most vociferously promoted and most heavily funded?”

"What will happen if in its anxiety to preserve a radical secularism, it detaches itself from its life-giving roots?"

Benedict didn’t bother providing direct replies to those rhetorical questions, but the implied answer to “what will happen?” seemed fairly obvious: nothing good.

In a similar vein, secularists often accuse Christians, and religious believers of all sorts, of being enemies of tolerance and dialogue because they purport to possess absolute truth. Benedict turned that blow around as well, suggesting that it’s actually secular relativism which is the true foe of dialogue.

“Not only do the proponents of this positivistic exclusion of the divine from the universality of reason negate what is one of the most profound convictions of religious believers,” the pope argued, “they also thwart the very dialogue of cultures which they themselves propose.”

“An understanding of reason that is deaf to the divine and which relegates religions into the realm of subcultures, is incapable of entering into the dialogue of cultures that our world so urgently needs,” he said.

Indeed, Benedict warned that a society under the sway of “radical relativism” will not be more reasonable or tolerant, but rather “more brittle and less inclusive” because they will struggle to recognize “what is true, noble and good.”

The Pope’s bottom line amounted to this: You academics prize academic freedom, tolerance and dialogue, and so do I. If you want to defend those values, Christianity is a better bet than secularism. Christianity is able to integrate reason and faith, while “radical secularism” breeds relativism and nihilism.

The nature of tonight’s event didn’t allow for any immediate sense of how the academics in Benedict’s audience reacted to this bit of verbal jiu-jitsu.

Nevertheless, the Pope’s rhetorical tradecraft at least seemed to offer confirmation of a point made by Professor Václav Hampl, a physiologist and rector of Charles University, in his welcoming remarks.

“The power of your words and your judgment has always been praised,” Hampl said to the pontiff, “even by your opponents.”

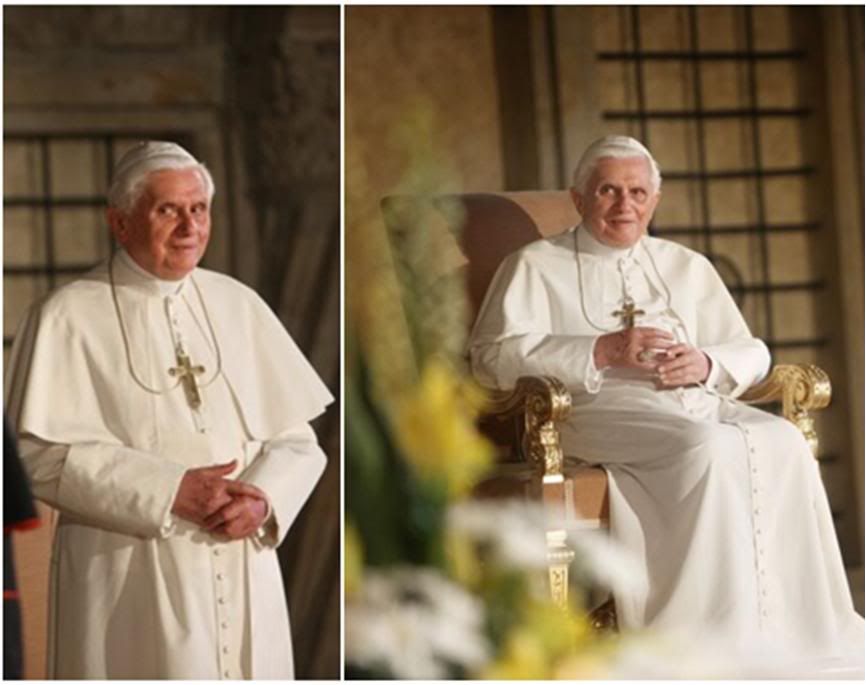

Before his speech, Benedict XVI was treated to a performance of several classical numbers by a university vocal chorus. Obviously touched, the Pontiff got up from his

throne ['Throne'? After the papal tiara went, I think it's improper to refer to the chair(s) provided for the Pope, special as they alway are, as a 'throne'] and went over afterwards to compliment the conductor.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 02/10/2009 18:10]