| | | OFFLINE | | Post: 18.975

Post: 1.622 | Registrato il: 28/08/2005

Registrato il: 20/01/2009 | Administratore | Utente Veteran | |

|

This message on science and knowledge is very much a companion piece to the Holy Father's discourse on beauty and art at the Sistine Chapel - every bit as inspiring and inspired by faith.

Between science and faith -

This message on science and knowledge is very much a companion piece to the Holy Father's discourse on beauty and art at the Sistine Chapel - every bit as inspiring and inspired by faith.

Between science and faith -

no conflict at all

on the horizon,

says Benedict XVI

Translated from

the 12/1/09 issue of

Pope Benedict XVI has sent Archbishop Rino Fisichella, rector of the Pontifical Lateran University, a message for the international conference this week entitled "From Galileo's telescope to evolutionary cosmology: Science, philosophy and theology in dialog".

Here is a translation of the Pope's message:

To my Venerated Brother

Mons. Rino Fisichella

Rector Magnificus of

the Pontifical Lateran University

I am happy to address my greeting to all the participants of the International Congress on the theme "From Galileo's telescope to evolutionary cosmology: Science, philosophy and theology in dialog".

I particularly greet you, Venerated Brother, as the promoter of this important time of reflection in the context of the International Year for Astronomy.,celebrating the fourth centenary of the invention of the telescope.

My thoughts also go to Prof. Nicola Cabibbo, president of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, who collaborated in preparing for the current sessions.

My cordial greetings to all the personalities who have come from different parts of the world who distinguish these days of study with their presence.

When one opens the Sidereus nuncius [The Starry Messenger, Galileo's first treatise describing his observations on the telescope] and reads the first statements of Galileo, what immediately shines forth is the Pisan scientist's wonder at what he himself had achieved:

"In these brief tract, I offer great things for the observation and contemplation of scholars of nature. Great, I say, because of the very excellence of the material in itself, the novelties that have never been seen before, and the instrument through which these things were made manifest to our senses" (Galileo Galilei, Sidereus nuncius, 1610, tr. P.A. Giustini, Lateran University Press 2009, p. 89).

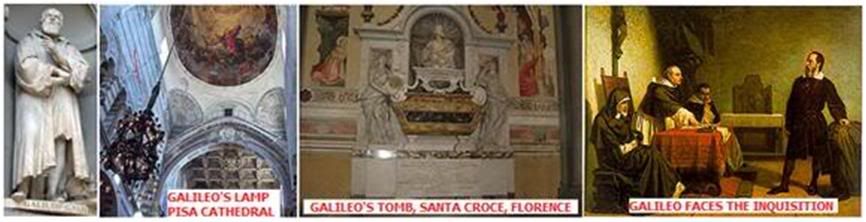

It was 1609 when Galileo for the first time turned towards the heavens an instrument "thought out by myself", as he wrote, "enlightened first of all by divine grace": the telescope.

What presented itself to his eyes is easy to imagine: wonder turned to emotion and then to enthusiasm that made him write: "It is certainly a great thing to add, to the immense multitude of fixed stars that could be seen till now with natural visive faculties, more numberless stars never seen before and which surpass ten times over the number of ancient stars known till now" (ibid.).

The scientist could observe with his own eyes much that was up to then merely the result of controversial hypotheses.

One would not be mistaken to think that Galileo's spirit of a profound believer would open up naturally before that vision to a prayer of praise, taking for his own the words of the Psalmist:

'O LORD, our Lord, how awesome is your name through all the earth! You have set your majesty above the heavens!... When I see your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and stars that you set in place - What are humans that you are mindful of them, mere mortals that you care for them?... You have given them rule over the works of your hands, put all things at their feet" (Ps 8, 1,4-5,7).

With this discovery, awareness grew in the culture about being at a crucial point in the history of mankind. Science had become something different from what the ancients had thought.

Aristotle had arrived at the sure knowledge of phenomena starting from evident universal principles. Now Galileo had shown concretely how to come closer and observe the phenomena themselves in order to grasp their secret causes.

The deductive method yielded to the inductive and opened the way to experimentation. The concept of science that had lasted for centuries now changed, paving the way towards a modern concept of the world and of man.

Galileo had penetrated into the unknown ways of the universe. He opened the door for the observation of ever greater spaces. Probably beyond his intentions, the invention of the Pisan scientist also allowed stepping back in time, provoking new questions on the origin of the cosmos itself, and making it emerge that even the universe, which had come from the hands of the Creator, has its own story: it "moans and suffers the pains of birth' - to use the expression of the Apostle Paul - in the hope of being liberated 'from the slavery of corruption to enter into the freedom of the glory of the children of God" (Rm 8, 21-22).

Even today the universe continues to raise questions to which observation cannot give a satisfactory answer: the natural and physical sciences do not suffice. Indeed, the analysis pf phenomena, if it remains closed within itself, risks making the cosmos seen like an insoluble enigma: But matter possesses an intelligibility that can speak to human intelligence to show a way that goes far beyond the phenomena themselves.

It is the lesson of Galileo that leads to this consideration. Was it not the scientist from Pisa who said God had written the book of nature in the language of mathematics?

And yet, mathematics is an invention of the human spirit in order to understand Creation. If nature is really structured in a mathematical language and the mathematics invented by man can come to understand it, it means that something extraordinary has occurred: The objective structure of the universe and the intellectual structure of the human subject coincide - subjective reason and reason objectified in nature are identical.

Ultimately, there is 'one reason' that links them and which invites us to look to the one Creative Intelligence. (cfr. Benedetto XVI, Address to the Youth of the Diocese of Rome, in Insegnamenti II [2004], 421-422).

Questions on the immensity of the universe, on its origin and its end, as on understanding it, do not admit a single response of a scientific nature. Whoever looks at the cosmos, following the lesson of Galileo, cannot simply stop at what he observes through the telescope - he should proceed further to ask himself about the sense and the end towards which all creation is oriented.

Philosophy and theology, at this point, take on an important role, to smooth out the way towards farther knowledge.

Philosophy faced with natural phenomena and the beauty of creation seeks, through reason, to understand the nature and ultimate finality of the the cosmos.

Theology, based on the revealed Word, scrutinizes the beauty and wisdom of the love of God, who left his imprints on created nature (cfr. St Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae, ia. q. 45, a. 6).

In this gnoseologic movement [gnoseology = the science of knowledge], both reason and faith are involved: both offer their light. The more the knowledge of the complexity of the cosmos grows, the more it requires instruments that are satisfactory.

There is no conflict at all on the horizon among the various sciences and the knowledge of philosophy and theology. On the contrary, it is only to the degree that they are able to enter into dialog and interchange their respective competencies will they be able to present truly effective results to contemporary man.

Galileo's discovery was a decisive stage for the history of mankind. Other great conquests took off from it, with the invention of instruments that have made the technological progress we have achieved so precious.

From satellites that observe various phases of the universe, which has paradoxically become 'smaller', to the most sophisticated machines used in biomedical engineering, everything demonstrates the greatness of human intelligence which, according to the Biblical command, is called on to 'master' all of creation (cfr. Gen 1, 28), to 'cultivate' it and to 'safeguard' it (cfr. Gen 2, 15).

But there is always a subtle risk underlying such conquests: that man puts his trust in science alone and forgets to raise his eyes beyond himself to that transcendent Being, Creator of all, who revealed his face of Love in Jesus Christ.

I am certain that the inter-disciplinarity at this Congress will allow grasping the importance of a unitary vision, fruit of common labor for the true progress of science in the contemplation of the cosmos.

Venerated Brother, I gladly join your academic commitment, asking the Lord to bless these days as well as the research by each of you.

From the Vatican

26 November 2009

The program of the conference (with speakers and their topics) may be found on

cms.pul.it/jx-link/575/3608

The program of the conference (with speakers and their topics) may be found on

cms.pul.it/jx-link/575/3608[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 01/12/2009 01:16] |