| | | OFFLINE | | Post: 17.642

Post: 334 | Registrato il: 28/08/2005

Registrato il: 20/01/2009 | Administratore | Utente Senior | |

|

On the 60th anniversary of D-Day in 2004, Pope John Paul II sent Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as his personal representative to the commemoration ceremonies.

On the 60th anniversary of D-Day in 2004, Pope John Paul II sent Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as his personal representative to the commemoration ceremonies.

The Pope could have sent any of the leading French cardinals then like Cardinal Etchegaray, who served as his personal envoy on several sensitive diplomatic missions, including the one to Saddam Hussein before the 2003 invasion of Iraq or even Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, whose Jewish parents were killed in a German concentration camp.

It is a tribute to the late Pope's openmindedness that he chose a German cardinal, who also happened to be his right-hand man, to represent him on that occasion. Expatriate Polish troops landed with the Allied troops in Normandy to fight the German forces that ahd overrun Europe.

Perhaps not by coincidence, 1960 was the first time that a German leader was invited to the D-Day commemoration. Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder represented his nation then.

Although Cardinal Ratzinger came to Normandy as a representative of the Vatican, he did not fail to do what any Christian German would and should do when visiting Normandy.

Besides visiting the cemeteries dedicated to the Allied war dead - he concelebrated Mass with US Cardinal George at the American cemetery on Colleville-sur-Mer - he also visited the German cemetery at La Cambe near Bayeux.

At least one prominent Jewish writer brought up Joseph Ratzinger's visit to La Cambe in 2004 as an accusation against Pope Benedict during his recent trip to the Holy Land - interpreting the act as a homage to the SS buried there.

The Germans buried at La Cambe also died while fighting for their country, as did the Allied war dead we remember today. It does not necessarily mean that all of them supported Hitler and his evil designs.

When he visited the war dead in La Cambe, Cardinal Ratzinger must have thought of himself and all his contemporaries and friends who were conscripted in their teens, against their will and their convictions, into German military service.

They, as much as the German dead who truly believed in Hitler and Nazism, deserved - and deserve - a prayer from the living that before their last breath, they managed to call on God and ask his forgiveness.

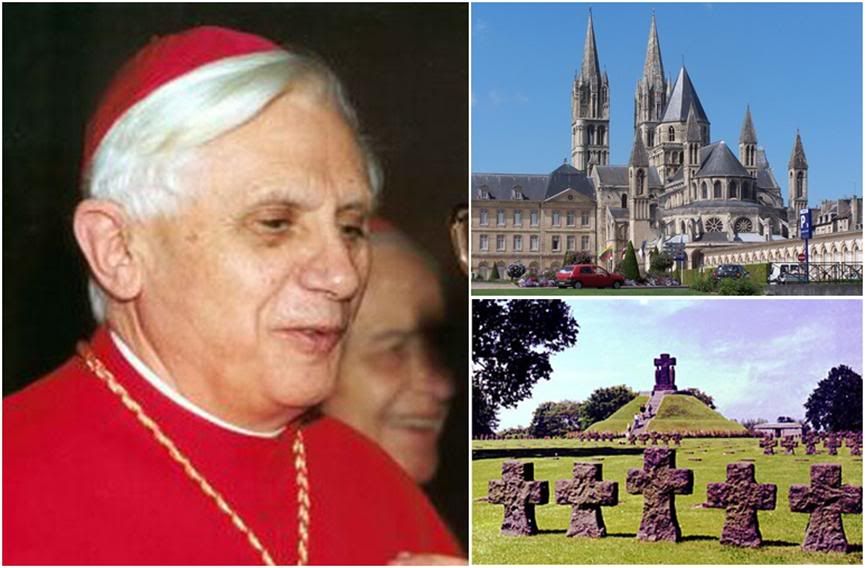

Cardinal Ratzinger in Caen, June 4, 2004. Inset photos show the Abbaye-aux-Hommes/St. Etienne Cathedral in Caen and the German cemetery at La Cambe.

Cardinal Ratzinger in Caen, June 4, 2004. Inset photos show the Abbaye-aux-Hommes/St. Etienne Cathedral in Caen and the German cemetery at La Cambe.

Here is the main text delivered by Cardinal Ratzinger (hee also delivered a homily at the Cathedral of Bayeux the day before) on that occasion five years ago at the Abbaye-aux-Hommes in Caen, the historic monastery founded by William the Conqueror in 1066 (the year of the Normal Conquest of England) who is also buried there. He begins it, remarkably, by speaking as a German.

Here is the main text delivered by Cardinal Ratzinger (hee also delivered a homily at the Cathedral of Bayeux the day before) on that occasion five years ago at the Abbaye-aux-Hommes in Caen, the historic monastery founded by William the Conqueror in 1066 (the year of the Normal Conquest of England) who is also buried there. He begins it, remarkably, by speaking as a German.

Rereading it now, it is an uncanny preview of the Regensburg lecture.

In search of freedom:

Against reason fallen ill

and religion abused

by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

Personal Representative of John Paul II

60th Anniversary Commemoration of the Normandy Landings

June 6, 2004

initially published in the German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and was translated from the German by Jeffrey Craig Miller. It was originally delivered in French.

On the 6th of June, 1944, when the landing of the allied troops in German-occupied France commenced, a signal of hope was given to people throughout the world, and also to many in Germany itself, of imminent peace and freedom in Europe.

What had happened? A criminal and his party faithful had succeeded in usurping the power of the German state. In consequence of such party rule, law and injustice became intertwined, and often indistinguishable.

The legal system itself, which continued, in some respects, still to function in an everyday context, had, at the same time, become a force destructive of law and right. This rule of lies served a system of fear, in which no one could trust another, since each person had somehow to shield himself behind a mask of lies, which, on the one hand, functioned as self defense, while, in equal measure, it served to consolidate the power of evil.

And so it was that the whole world had to intervene to force open this ring of crime, so that freedom, law and justice might be restored.

We give thanks at this hour that this deliverance, in fact, took place. And not just those nations that suffered occupation by German troops, and were thus delivered over to Nazi terror, give thanks.

We Germans, too, give thanks that by this action, freedom, law and justice would be restored to us. If nowhere else in history, here clearly is a case where, in the form of the Allied invasion, a justum bellum worked, ultimately, for the benefit of the very country against which it was waged.

To Europe was given, after 1945, a period of peace of such duration as our continent had never seen in its entire history.

To no small degree, this was the accomplishment of the first generation of post-war politicians -- Churchill, Adenauer, Schuman, De Gasperi - whom we have to thank at this hour: We are to give thanks that it was not punishment that was fixed upon, nor again revenge and the humiliation of the defeated, but rather that all should be accorded their rights.

Let us say it openly: These politicians took their moral ideas of state and right, peace and responsibility, from their Christian faith, a faith that had undergone the tests of the Enlightenment, and in opposing the perversion of justice and morality of the party-states, had emerged re-purified.

They did not want to found a state upon religious faith, but rather a state informed by moral reason, yet it was their faith that helped them to raise up again a reason once distorted by, and held in thrall to ideological tyranny.

Across Europe ran a frontier, and not just across our continent, but dividing the entire world. A great part of Central Europe and Eastern Europe came under the domination of an ideology that subjected state to party, in the end, effacing the difference.

Here, again, the result was the rule of lies. Visible after the collapse of these dictatorships, was the enormous destruction - economic, ideological, and psychological - which followed from this rule. In the Balkans, there were the entanglements of belligerency, bringing, along with the admittedly ancient burdens of history, new explosions of violence.

If Europe, since 1945, was permitted to experience a period of peace (the complications in the Balkans aside), the state of the world taken as a whole was surely far from peaceful.

From Korea, through Vietnam, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Algeria, the Congo, Biafra-Nigeria, to the conflicts in Sudan, in Rwanda-Burundi, Ethiopia, Somalia, Mozambique, Angola, Liberia, and on to Afghanistan and Chechnya, stretches a bloody arc of armed conflict, to which may be added the struggles in and concerning the Holy Land, and in Iraq. This is not the place to undertake a typology of theses wars. But two, in some ways new phenomena, I would like to examine more closely.

In the first, the cohesiveness of the law, and the capacity of diverse communities to live together, seem suddenly to break apart. Somalia, it seems to me, presents a typical example of the breakdown of the sustaining power of law, and with it, the collapse into chaos and anarchy.

The reasons for this dissolution of law and the capacity for reconciliation are many fold. We can list a few.

In all these realms, the cynicism of ideology has benighted conscience. Side by side with the cynicism of ideology, and often closely bound together with it, is the cynicism of the interests and of big business, the ruthless exploitation of the earth’s reserves. Here also is the good shoved aside by the expedient, and might setup in the place of right.

The other new phenomenon is terror. The threat that terror’s network, (and/or that of garden-variety organized crime) growing ever stronger and widespread, might gain access to atomic weapons and to biological weapons, constitutes an increasingly frightening danger.

For as long as these destructive capabilities remained exclusively in the hands of the great powers, one could always hope that reason, and knowledge of the danger that their use would pose to their own people and state, would preclude their employment of these weapons systems.

Terror cannot be overcome by force alone. Granted that the defense of right and law against a violence that would destroy them, may and must, for its own part, according to circumstances, have recourse to carefully calibrated force, for the protection of law and right.

But in order that force in the defense of law and right shall not be itself do wrong, it must subject itself to stringent measures. It must pay heed to the causes of terror, which so often has its source in standing injustice, not addressed by effective measures. It must thus, by every means, address the elimination of that antecedent injustice.

Above all is it important to vouchsafe forgiveness in advance, in order that the circle of violence may be broken. Where a merciless eye-for-an-eye obtains, there is no way to break free of violence.

Acts of humanity, which have the power to break the circle of violence, which seek the human in the other and call out to his humanity, are essential, though they seem, at first glance, a waste of effort.

In all these cases it is important that no one particular power act as the champion of justice. All too easily can interest interfere with action, and contaminate one’s view of what is just. Most urgent is a genuine jus genitum, free from hegemonic predominance and action which follows from it: only thus can it remain clear that what is at stake is the defense of collective law and right, and those also of them who stand, so to speak, on the other side.

But in the contemporary clash between the great democracies and an Islamic-motivated terror, deeper questions come into play. Two great cultural systems with very different forms of power and moral orientation appear to be in conflict - the “West” and Islam.

But what is it, the West? And what is Islam? Both are multi-layered worlds with great internal differences - worlds that, in many ways, also intersect. In this respect, the crude antithesis West-Islam, does not apply.

Some incline toward a greater deepening of opposition: Enlightened reason is set up against a fundamentalist-fanatical form of religion.

Truly, the relationship between reason and religion is of the first importance in this situation, and the struggle for the right relationship belongs at the heart of our concern for the cause of peace.

There are pathologies of religion - we see this; and there are pathologies of reason - we see this, too, and both pathologies are life threatening for peace - indeed, in an age of global power structures, for humanity as a whole.

God or the divine can make for the absolutizing of one’s own power, one’s own interests. But there are pathologies of reason totally disconnected from God. One would probably denominate Hitler as irrational.

But the great explicators and executors of Marxism understood themselves very much as construction engineers, redesigning the world in accordance with reason. Perhaps the most dramatic expression of this pathology of reason is Pol Pot, where the barbarity of such a reconstruction of the world makes its most direct appearance.

But the evolution of intellect in the West, also, inclines ever more toward the destructive pathologies of reason. Was not the atom bomb already an overstepping of the frontier, where reason instead of being a constructive power, sought its potency in its capacity to destroy?

When reason, now with the investigation into the genetic code, snatches at the roots of life, ever more does it tend to see human being, not any longer as the gift of God (or of Nature), but as a product to be made.

Man is “made,” and what man can make, he can also destroy. In all this is the concept of reason made ever flatter. Only what is verifiable, or to be more exact, falsifiable, counts as rational; reason reduces itself to what can be confirmed by an experiment.

The entire domain of the moral and the religious, belongs then to the realm of the “subjective” - it falls outside of common reason altogether.

One no longer sees that as tragic for religion - each one finds his own - which means that religion is seen as a kind of subjective ornament, providing a possibly useful kind of motivation. But in the domain of the moral, one seeks to be better.

Reason fallen ill and religion abused, meet in the same result.

To a reason fallen ill, all recognition of definitively valid values, all that stands on the truth capacity of reason, appears finally as fundamentalism. All that remains is reason’s dissolution, its deconstruction, as, for example, Jacques Derrida has set it out for us.

He has “deconstructed” hospitality, democracy, the state and finally, the concept of terrorism, only to stand in horror in the face of the events of September 11th.

A form of reason that can acknowledge only itself and the empirical conscience paralyzes and dismembers itself.

A form of reason that wholly detaches itself from God, and wants simply to resettle Him in the zone of subjectivity, has lost its compass, and has opened the door to the powers of destruction.

It is the duty, in these times, of us Christians to direct our concept of God to the struggle for humanity. God himself is Logos, the rational first cause of all reality, the creative reason out of which the world came to be, and which is reflected in the world.

God is Logos - Meaning, Reason, Word, and so it is through the way of reason that man encounters God, through the espousal of a reason that is not blind to the moral dimension of Being.

There is a second point. It belongs, as well, to a Christian belief in God, that God - eternal reason - is Love. It follows, too, that He does not represent a relationless, self-orbiting Being. Precisely because He is sovereign, because he is the Creator, because He embraces everything, He is Relation and He is Love.

Belief in the God who became human in Jesus Christ, and in his suffering and death for humanity, is the highest expression of this conviction: that the heart and hinge of all morality, the heart and hinge of Being itself, and its inmost source is Love.

This declaration represents the strongest repudiation of any ideology of violence whatsoever; it is the true apologia of humankind and of God. But let us not forget that the God of Reason and Love, is also the Judge of the world - the guarantor of justice - before whom all men must make account. There is a justice love will not annul.

There is yet a third element of Christian tradition that I wish to mention, that, in the afflictions of our time, is of fundamental importance.

Christian belief - following in the way of Jesus - has negated the idea of political theocracy. It has - to express it in modern terms - produced the worldliness of states, wherein Christians along with the adherents of other convictions live together in peace.

Thus is distinguished the Christian belief that the Kingdom of God does not exist as a political reality, and cannot so exist, but rather, through faith, hope and love is it attained, and the world transformed from within.

But under the conditions of temporality, the Kingdom of God is no worldly empire, but rather, a call for the freedom of humanity and a support for reason that it may fulfill its own mission.

The temptations of Jesus were ultimately about this distinction, about the rejection of political theocracy, about the relativity of states and reason’s own law, as well as about the freedom to choose, which is meant for every person.

In this sense, the secular state follows from of a fundamental Christian decision, even if it required a long struggle to understand this in all its consequences. This worldly, “secular” state incorporates, in its essence, the balance between reason and religion, which I have tried here to present.

However, it stands against secularism as an ideology, which would, as it were, construct the state from pure reason, released from all historical roots, and which can thus recognize no moral foundations that are not discernable to reason.

All that is left it, in the end, is the positivism of the greatest number, and with it the abasement of right; ultimately, it is to be governed by a statistic.

If the countries of the West were to commit wholly to this path, they could not indefinitely withstand the press of the ideologues and political theocrats.

Even a secular state may - indeed, must - find its support in the formative roots from which it grew, it may and must acknowledge the foundational values without which, it would not have come to be, and without which, it cannot survive. Upon an abstract, an a-historical reason, a state cannot endure.

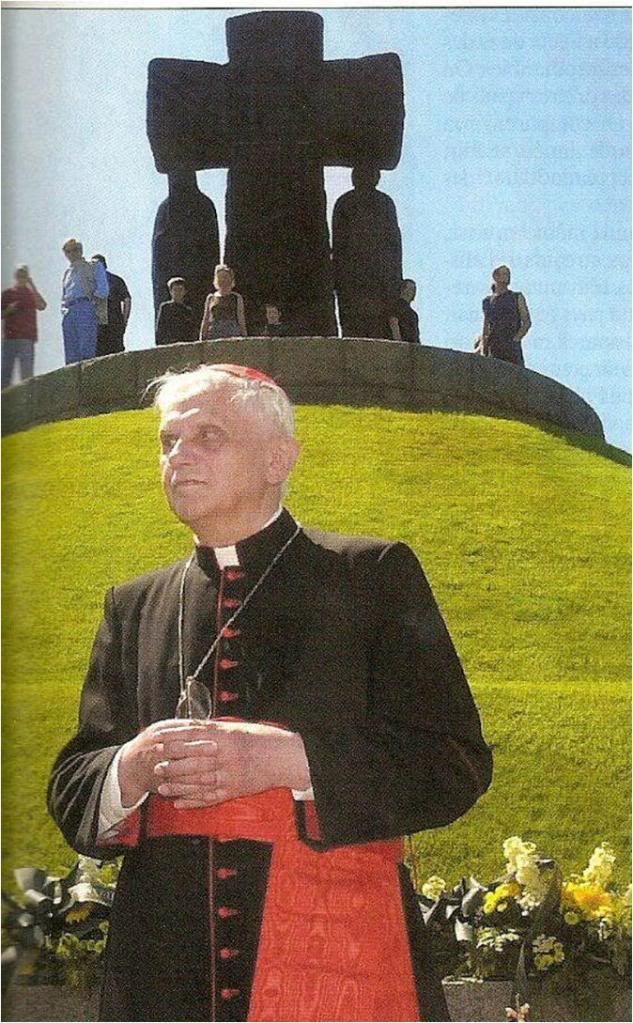

With great thanks to Flo in the PRF, who shares with us this memento of Cardinal Ratzinger at La Cambe in 2004.

Besides its historic and symbolic value, it's also a great photograph!

There was a New Yorker article in 2006 referring to the 2004 visit to La Cambe (and other commentary on Joseph Ratzinger's public comments about Nazi Germany), that is available online only in abstract form, as follows. Notwithstanding its title 'Forgiveness', teh abstract makes it clear the article was yet another attempt to establish a 'culpable' association of Joseph Ratzinger to the Nazi regime:

Timothy W. Ryback, Annals of Religion, “Forgiveness,” The New Yorker, February 6, 2006, p. 66-73

There was a New Yorker article in 2006 referring to the 2004 visit to La Cambe (and other commentary on Joseph Ratzinger's public comments about Nazi Germany), that is available online only in abstract form, as follows. Notwithstanding its title 'Forgiveness', teh abstract makes it clear the article was yet another attempt to establish a 'culpable' association of Joseph Ratzinger to the Nazi regime:

Timothy W. Ryback, Annals of Religion, “Forgiveness,” The New Yorker, February 6, 2006, p. 66-73

Writer tells about Ratzinger's visit, as the personal representative of Pope John Paul II, to France for the sixtieth anniversary of the Allied landings in Normandy.

After a ceremony at Omaha Beach, Ratzinger went to the La Cambe cemetery where 21,000 German war dead, including members of the S.S., are buried. It was noted in Germany that Gerhard Schroeder, the German Chancellor, excluded La Cambe from his itinerary because of a controversial 1985 visit by Helmut Kohl and Ronald Reagan to the Bitburg cemetery, where S.S. officers are also buried.

At La Cambe, Ratzinger spoke about the German soldiers' Pflicht-blind [obedience to duty] - which had been exploited for evil purposes. He insisted that this did not dishonor the service and sacrifice to the fatherland.

He blamed the Allies for driving Germany towards Nazism through the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles. [As I have not found any version of the cardinal's remarks in La Cambe, i would like to know how he phrased this exactly. But it is historical fact that the exacting terms of the post-Word War I Treaty of Versailles imposed by the victorious alleis on Germany led to the German economic collapse that allowed Hitler and National Socialism to win the elections of 1933.]

When Ratzinger became Pope, the media made much of the fact that he had been a member of the Hitler Youth and served in the German Wehrmacht. Not nearly so much attention was paid to his public life after the war, particularly his apparent reluctance to engage in the public soul-searching the world has come to expect of Germans. He is more circumspect when it comes to collective German responsibility for the Holocaust…

Tells about the oath of loyalty to the state that German Catholic bishops have been required to take since 1933… Discusses Ratzinger's tenure as archbishop of Munich and Freising, where the memorial site to the Dachau concentration camp is located.

Tells the history of Dachau, which held as many as 2,500 Catholic priests and seminarians, half of whom died there. In 1943, Ratzinger's military unit was housed in a subsidiary camp of Dachau where slave laborers were kept…

Writer notes that there is no record of Ratzinger having made a statement about Dachau during his tenure as archbishop. People who know him point out that Ratzinger did visit Auschwitz and that he helped pioneer reconciliation between Catholics and Jews…

Writer discusses other occasions when Ratzinger has been notably silent about German culpability. Writer also discusses the ethics of Ratzinger's position within Catholic theology with, among others, Peter Seewald, a journalist who interviewed Ratzinger, Martin Marty, a Lutheran pastor, Cardinal Avery Dulles, a professor of religion, John Palikowski, a professor of social ethics, and Siegfried Wiedenhofer, a former student of Ratzinger's. Wiedenhofer agreed that something was missing in Ratzinger's remarks at La Cambe.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 08/06/2009 23:40] |