| | | OFFLINE | | Post: 17.612

Post: 308 | Registrato il: 28/08/2005

Registrato il: 20/01/2009 | Administratore | Utente Senior | |

|

Earlier posts for today, June 3, on preceding page.

Earlier posts for today, June 3, on preceding page.

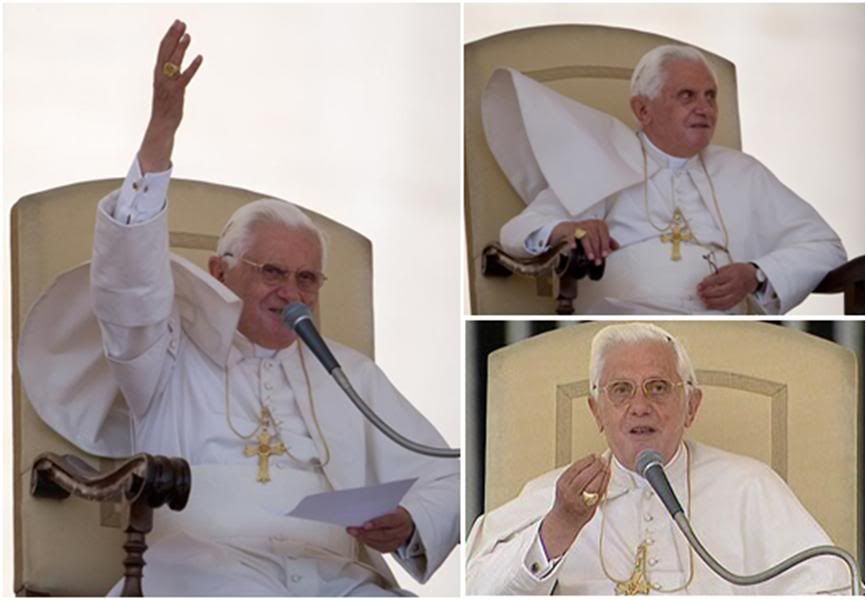

GENERAL AUDIENCE TODAY

GENERAL AUDIENCE TODAY

Vatican City, June 3 (AsiaNews) – At work, “with its pressing rhythm” and on vacation, we must “reserve” a moment for God, opening up to Him “with a thought, a meditation, a small prayer, and “not forget the Lord’s Day”, which is “the day of liturgy, of sacred music, so we can perceive the beauty of the Church of God and allow it enter our beings: only in this way can our life become true and great life”.

That was Benedict XVI’s call to 25 thousand people present at his general audience, during which he traced the life and legacy of an “extraordinary figure” from the High Middle Ages, Saint Rabanus Maurus, one of the protagonists of Carolingian culture.

Here is how the Pope synthesized the catechesis in English:

Here is how the Pope synthesized the catechesis in English:

Our catechesis today deals with another great monastic figure of the High Middle Ages, Rabanus Maurus.

Rabanus entered monastic life at a young age as an oblate, was trained in the liberal arts and received a broad formation in the Christian tradition.

As the Abbot of Fulda and then as Archbishop of Mainz, he contributed through his vast learning and pastoral zeal to the unity of the Empire and the transmission of a Christian culture deeply nourished by the Scriptures and the Fathers of the Church.

From his youth he wrote poetry, and he is probably the author of the famous hymn Veni Creator Spiritus. Indeed, his first theological work was a poem on the Holy Cross, in which the poetry was accompanied by an illuminated representation of the Crucified Christ.

This medieval method of joining poetry to pictorial art sought to lift the whole person – mind, heart and senses – to the contemplation of the truth contained in God’s word.

In the same spirit Rabanus sought to transmit the richness of the Christian cultural tradition through his prolific commentaries on the Scriptures, his explanations of the liturgy and his pastoral writings.

This great man of the Church continues to inspire us by his example of an active ministry nourished by study, profound contemplation and constant prayer.

Here is a translation of the Pope's full catechesis:

Here is a translation of the Pope's full catechesis:

CATECHESIS ON RABANUS MAURUS

Dear brothers and sisters,

Today I wish to speak of a truly extraordinary personage from the Latin West - the monk Rabanus Maurus. Together with men like Isidore of Seville, Bede the Venerable, Ambrose Autpert, whom I have talked about in preceding catecheses, he kept in contact, in that historical period called the High Middle Ages, with the great culture of the ancient wise men and Christian fathers. Often referred to as 'praeceptor Germaniae' (Teacher of Germany), Rabanus was extraordinarily prolific.

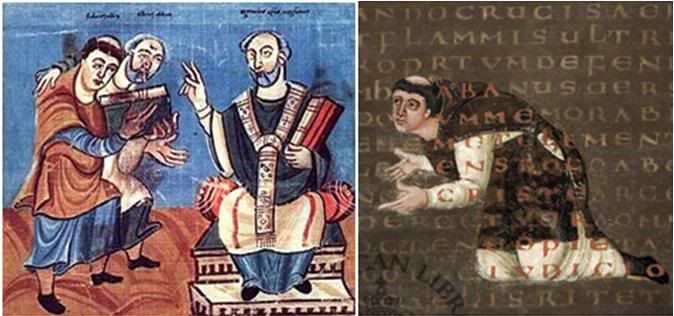

Left, Rabanus presenting his work to Olgar of Mainz; right, Rabanus portrays himself as a humble monk in one of his cryptic pictorial poems.

With his absolutely exceptional capacity for work, he contributed perhaps more than anythings else to keep alive that theological, exegetic and spiritual culture from which the succeeding centuries had drawn.

Great monastic figures like Pier Damiani, Peter the Venerable and Bernard of Clairvauz looked back to him, as did ever more solid numbers of the secular clergy who in the 12th and 13th centuries gave life to one of the most beautiful and fecund flowerings of human thought.

Born in Mainz around 780, Rabanus entered the monastery at a very young age; he acquired the other name Maurus after the young Maurus in Book II of St. Gregory the Great's Dialogues, who had been entrusted as a boy by his own parents, who were Roman nobles, to the abbot Benedict of Norcia.

Rabanus availed of his precocious introduction as a 'puer celatus'(literally, hidden boy), in the Benedictine monastic world, and the fruits that he received from this, for his human, cultural and spiritual growth, and would in itself open a most interesting glimpse not only into the life of monks and that of the Church, but also on the entire society of his time, usually referred to as the 'Carolingian' [named for Charlemagne] age.

Of the times, or perhaps of himself, Rabanus Maurus wrote: "There are those who had the good fortune to be introduced to knowledge of the Scriptures from their infancy ('a cunabulis suis', from their cradle] and have been so well nourished with the food offered them by the Holy Church, enough to be promoted, with the appropriate education, to the highest sacred orders" (PL 107, col 419BC).

The extraordinary culture which distinguished Rabanus Maurus brought him early to the attention of the great figures of his time. He became the adviser of princes. He worked to guarantee the unity of the [Holy Roman] Empire, and at the broadest cultural level, he never drew back from offering whoever asked him a well-considered response, preferably drawn from the Bible and Patristic texts.

First elected Abbot of the famous Monastery at Fulda, and then Archbishop of his native city Mainz, he did not cease from pursuing his studies, demonstrating with the example of his life, that one can be simultaneously at the disposition of others without depriving oneself of congruent time for reflection, study and meditation.

And so, Rabanus Maurus was an exegete, philosopher, poet, pastor and man of God. The dioceses of Fulda, Mainz, Limburg and Wroclaw venerate him as a saint or a blessed one. His works make up six volumes of Migne's Latin patrology.

Most likely, we owe him one of the most beautiful and well-known hymns of the Latin Church, the Veni Creator Spiritus, extraordinary synthesis of Christian pneumatology [study of the Holy Spirit].

Rabanus's theological effort was primarily expressed, in effect, in the form of poetry, and its object was the mystery of the Holy Cross in a work entitled De laudibus Sanctae Crucis [In praise of teh Holy Cross], conceived in such a way as to propose not just conceptual contents but exquisitely artistic devices, using both the poetic form as well as pictorial form in the same 'coded' manuscript.

Iconographically proposing among the lines of his poems the image of the crucified Christ, he writes for instance:

"Here is the image of the Savior who, through the positioning of his limbs, makes sacred for us that most celebrated, sweetest and most beloved form of the Cross, so that, believing in his name and obeying his commandments, we may enter eternal life, thanks to his Passion.

"Thus every time we raise our eyes to the Cross, let us remember him who suffered for us in order to wrench us from the power of the shadows, who accepted death to make us heirs to eternal life" (Lib. 1, Fig. 1, PL 107 col 151 C).

This method of combining all the arts, the intellect, the heart and the senses, which came from the East, would receive enormous development in the West, reaching unequalled peaks in the miniaturized coded Bibles and other works of faith and art which flowered in Europe until the invention of the printing press and beyond that.

In any case, that method in Rabanus Maurus demonstrated an extraordinary awareness of the need to involve in the experience of faith not only the mind and the heart, but also the senses through the other aspects of aesthetic taste and human sensitivity that bring man to benefit from the truth with all of himself - 'spirit, soul and body'.

This is important: faith is not only thought, but it touches all of our being. Since God became man of flesh adn blood, he entered the world of the senses, then we must seek to encounter God in all the dimensions of our being.

Thus the reality of God, through faith, penetrates our being and transforms it. That is why Rabanus Maurus concentrated his attention above all on liturgy as the syntehsis of all the dimensions of our perception of reality. This intuition makes him extraordinarily relevant.

Another thing he left us are the famous 'Carmina' [medieval songs in Latin and some German, using rhynmed lyrics as the Carmina Burana, or carmina from the Benedictine abbey of Beuern] offered to be used above all in liturgical celebrations. In fact, since Rabanus was above all a monk, his interest in liturgical celebration was only to be expected.

He did not devote himself to poetry as an end in itself, but he used art and every other form of knowledge to deepen knowledge of the Word of God. Thus he sought, with extreme commitment and rigor, to introduce his contemporries - especially bishops, priests and deacons - to an understanding of the profoundly theological and spiritual significance of all elements in liturgical celebration.

Thus, he tried to understand and propose to others the hidden theological significances of rites, drawing from the Bible and the tradition of the Fathers. He did not hesitate to declare - our of honesty as well as to give greater weight to his explanations, the patristic sources to which he owed his own knowledge.

And he continued to avail of those sources freely but with careful discernment in order to continue the development of Patristic thought.

At the end of the 'First Epistle' addressed to a 'corepiscopo' ['the heart of a bishop'] in the diocese of Mainz, for instance, after responding to requests for clarification on the rules to follow in the exercise of pastoral responsibility, he writes: ""We have written you all these as we have deduced from Sacred Scriptures and the canons of the Fathers. But you, most holy man, must make your decisions as you think best for you, case by case, seeking to temper your own valuation in a way that will guarantee direction in everything, because that is the mother of all virtues" (Epistulae, I, PL 112, col 1510 C).

Thus, one sees the continuity of Christian faith, which has its beginnings in the Word of God: but this Word is always a living Word - it develops and is exopressed in new ways, but always consistent with all the structure, with the entire edifice, of the faith.

Since the Word of God is an integral part of the liturgical celebration, Rabanus Marcos dedicated to it his greatest efforts during his entire existence.

He provided appropriate exegetical explanations of almost all the books in both the Old and New Testaments with a clearly pastoral intention, which he justified in words like these: "I wrote these things... synthesizing explanations and proposals from many others to offer a service to the poor reader who does not have many books at his disposition, and also to make it easy for those who are unable to enter into a deeper understanding of the significant discoveries of the Fathers of antiquity" (Commentariorum in Matthaeum praefatio, PL 107, col. 727D).

In fact, in commenting on Biblical texts, he drew fully from the Fathers, particularly Jerome, Ambrose, Augustine and Gregory the Great.

His marked pastoral sensitivity brought him to take on one of the problems most ddeply felt among the faithful and the sacred ministers in his time: that of Penitence. He compiled 'Penitentiaries" - as he called them - in which, according to the sensibility of the time, he listed sins and their corresponding penances, using as much as possible reasons taken from the Bible, the decisions of Church Councils, and papal decrees. Indeed, the Carolingians used these texts in their attempts to reform the Church and society.

For his pastoral intentions, he wrote works like De disciplina ecclesiastica and De institutione clericorum, in which, drawing from Augustine above all, Rabanus explained to the simple folk and to the priests of his diocese the fundamental elements of the Christian faith - they were sort of small catechisms.

I wish to conclude the presentation of this great 'man of the Church' by citing some of his words which reflect well his basic conviction: "Whoever is negligent in contemplation ["qui vacare Deo negligit") deprives himself of a vision of God's light. And whoever then allows himself to be taken over indiscreetly by other concerns and allows his toughts to be distracted by the tumult of worldly events, condemns himself to the absolute impossiblity of penetrating the secrets of the invisible God" (Lib. I, PL 112, col. 1263A).

I think Rabanus Maurus addresses these words even to us today: During times of work, with its frenetic rhythms, and during vacations, we should reserve moments for God. We must open our life to him by turning to him with a thought, a reflection, a brief prayer, and above all, let us not forget Sunday as the Lord's day, the day of liturgy, in order to perceive in the beauty of our churches, of sacred music and the Word of God, the beauty of God himself, allowing him to enter our being. Only then can our life become great. It becomes true life.

The illustrations are from Rabanus's De laudibus Sanctae Crucis described as 'a collection of twenty-eight encrypted religious poems, rendered before 814 AD (using) a ciphering system of 36 lines containing 36 letters evenly spaced on a grid. In this grid, Maurus included figurative images, putting the poems in visual terms. The poem filling the cypher grid was enriched by these smaller images, as most of the letters contained within them created tiny individual poems.'

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 04/06/2009 04:09] |