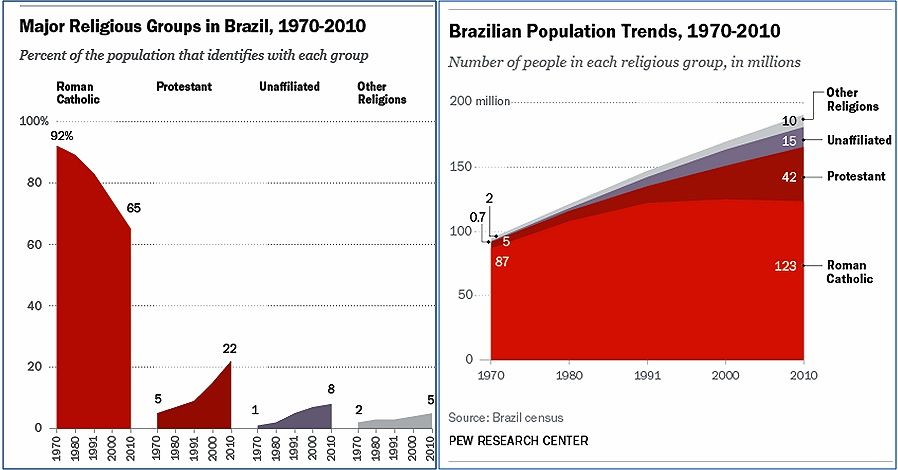

In a www.chiesa article yesterday, Sandro Magister point out that less than half the population of Rio de Janeiro now identifies as Catholic, which is a shocking as well as sobering fact. It's not that Brazilians are losing their faith. Only 15 million in a population of about 190 million in 2010 said they had no religious affiliation. But in the world's largest Catholic nation (123 million Catholics), the Church continues to lose ground to the new Protestant denominations. Here is the latest report from the Pew Center using census data from 2010.

Brazil’s changing religious landscape:

Roman Catholics in decline, Protestants on the rise

July 18, 2013

Since the Portuguese colonized Brazil in the 16th century, it has been overwhelmingly Catholic. And today Brazil has more Roman Catholics than any other country in the world – an estimated 123 million.1

But the share of Brazil’s overall population that identifies as Catholic has been dropping steadily in recent decades, while the percentage of Brazilians who belong to Protestant churches has been rising.

Smaller but steadily increasing shares of Brazilians also identify with other religions or with no religion at all, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Brazilian census data.

Brazil’s total population more than doubled over the last four decades, increasing from approximately 95 million to more than 190 million. Between 1970 and 2000, the number of Catholics in the country rose, even though the share of the population that identifies as Catholic was falling.

But from 2000 to 2010, both the absolute number and the percentage of Catholics declined; Brazil’s Catholic population fell slightly from 125 million in 2000 to 123 million a decade later, dropping from 74% to 65% of the country’s total population.

The number of Brazilian Protestants, on the other hand, continued to grow in the most recent decade, rising from 26 million (15%) in 2000 to 42 million (22%) in 2010.

“Protestant” is broadly defined here to include Brazilians who identify with historically mainline and evangelical Protestant denominations as well as those who belong to Pentecostal denominations, such as the Assemblies of God and the Foursquare Church.

It also includes members of independent, neo-Pentecostal churches, such as the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God and the God is Love Pentecostal Church, both of which were founded in Brazil. But in keeping with categories in the Brazilian census, it does not include Mormons or Jehovah’s Witnesses.

In addition, the number of Brazilians belonging to other religions – including Afro-Brazilian faiths such as Candomblé and Umbanda; spiritist movements like the one related to the late Chico Xavier; and global religions such as Buddhism and Islam – has been climbing.

About 2 million Brazilians belonged to these other religions in 1970. By 2000, adherents of religions other than Catholicism and Protestantism numbered about 6 million (4% of Brazil’s population), and as of 2010, the group had grown to 10 million (5%).

Finally, the number of Brazilians with no religious affiliation, including agnostics and atheists, also has been growing. In 1970, fewer than 1 million Brazilians had no religious affiliation. By 2000, that figure had jumped to 12 million (7%). In the most recent decade, the unaffiliated continued to expand, topping 15 million (8%) in Brazil’s 2010 census.

The growth of Pentecostalism in Brazil has been particularly pronounced. In Brazil’s 1991 census, about 6% of the population belonged to Pentecostal or neo-Pentecostal churches. By 2010, that share had grown to 13%.

Meanwhile, the percentage of Brazilians who identify with historical Protestant denominations, such as Baptists and Presbyterians, has remained fairly steady over the last two decades at about 3% to 4% of the population.

The Brazilian census also contains a third category of Protestants, labeled “unclassified.” That group has grown from less than 1% of Brazil’s population in 1991 to 5% in 2010.2

The rapid growth of Pentecostals and other Protestants in Brazil cannot be explained fully by demographic factors, such as fertility rates or immigration. Brazilian census data from 2000 indicate that total fertility rates for Protestants are about the same as for Catholics. In addition, less than 1% of Brazil’s population is foreign born – too small a percentage for immigration to make a significant difference in the religious composition of the country as a whole.

Rather, the main factor in the growth of Protestantism in Brazil appears to be religious switching, or movement from one religious group to another. The country’s decennial census does not ask Brazilians whether they have switched religions. But a 2006 Pew Research survey of Brazilian Pentecostals found that nearly half (45%) had converted from Catholicism.

Catholics have decreased as a share of Brazil’s population while Protestants have risen among men and women, young and old, people with and without a high school education, and those living in both urban and rural areas.

But the changes have been particularly pronounced among younger Brazilians and city dwellers, as shown in the tables below. For example, the percentage of Brazilians ages 15-29 who identify as Catholic has dropped 29 percentage points since 1970, and the share of Catholics in Brazil’s urban population has fallen 28 points.

Brazilian Catholics tend to be older and live in rural areas, while Protestants tend to be slightly younger and live in urban areas. Brazilians with no religious affiliation also are younger, on average, than the population as a whole and are more likely to reside in urban settings. The remainder of this report examines these demographic patterns in more detail.

Factors affecting differences in

religious affiliation among Brazilians

Age

Generational change has contributed to the declining number of Catholics in Brazil. As of 2010, nearly three-quarters (73%) of Brazilians ages 70 and older are Catholic, while fewer than two-thirds (63%) of those ages 15-29 identify as Catholic.

Younger cohorts are somewhat more likely than older Brazilians to be Protestant or to have no religious affiliation. As of 2010, for example, Protestants make up more than a fifth (22%) of Brazilians ages 15-29, compared with 17% of those 70 and older. And 10% of 15-to 29-year-olds had no religious affiliation in 2010, while just 4% of Brazilians ages 70 and older are unaffiliated.

Urban versus rural

Brazil’s overall population has become increasingly urban. In 1970, about half (56%) of Brazilians lived in urban areas; as of 2010, more than eight-in-ten (84%) do. As a result, all of Brazil’s religious groups have become increasingly urban – but some more so than others.

In general, Catholics are more likely than other religious groups to live in rural areas. According to the 2010 census, more than three-quarters (78%) of Brazilians who live in rural areas are Catholic, compared with roughly six-in-ten (62%) urban dwellers.

In 1970, the religious profiles of rural and urban residents were very similar, but the differences have become more pronounced in recent decades. Today, Brazil’s cities are home to a much lower share of Catholics than the country’s rural areas. For example, less than half (46%) of the population of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s second-largest city, is affiliated with the Catholic Church.

Gender

According to the 2010 census, about equal percentages of Brazilian men (65%) and women (64%) are Catholic. By contrast, a slightly higher percentage of women (24%) than men (20%) identify as Protestant, while a slightly higher share of men (10%) than women (6%) have no religious affiliation. Similar shares of men (5%) and women (6%) belong to other religions.

These gender patterns have become more distinct over time. For instance, the religious profiles of men and women were quite similar in the 1970s and 1980s. But over the past two decades, the share of women who are Protestant has ticked up, as has the share of men who are religiously unaffiliated.

Education

Looking at two education levels – completion of high school and less education – there are only minor differences in the percentages of Catholics, Protestants and the unaffiliated in each group. The notable exception is that a greater share of adults who have completed high school belong to other religions (9%) compared with those who have less education (4%). This is particularly true of Brazilians belonging to spiritist movements. As of 2010, the share of spiritists who have completed high school (70%) is almost twice as high as in the general public (36%).

]TThe rest of the summary is an explanation of the methodology used in the survey and the sources for the census data used.]

This report is part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, an effort funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation to analyze religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

On the eve of Benedict XVI's apostolic visit to Brazil in May 2007, Sandro Magister wrote a lengthy commentary in which he claimed tendentiously that Benedict XVI had virtually 'ignored' Latin America during the first two years of his Pontificate. Among other things, he noted this::

On the eve of Benedict XVI's apostolic visit to Brazil in May 2007, Sandro Magister wrote a lengthy commentary in which he claimed tendentiously that Benedict XVI had virtually 'ignored' Latin America during the first two years of his Pontificate. Among other things, he noted this::

In 1980, when John Paul II went to Brazil for the first time, Catholics had a near monopoly with 89 percent of the population. In the 2000 census, they had fallen to 74 percent, and today in Sao Paolo, Rio de Janeiro, and the urban areas, they are under 60 percent.

I commented at the time:

If, in the 20-year period spanned by these statistics, the situation for Catholicism in Latin America grew worse - despite 4 Papal visits to Mexico, 2 visits to Brazil, and at least one each to almost all the other countries of Latin America, by the Pope who has been the most 'ad extra' in modern history - why is Benedict being judged now - after two years in office - for something that, clearly, not the Pope, nor any single institution, is capable of solving overnight?

The problem of Latin American Catholicism is obviously not a simple one - and how can the bishops of Latin America be unaware of it? [Magister also claimed in the article that the working document for the Aparecida conference of Latin American and Caribbean bishops, which Benedict XVI opened during his trip to Brazil, 'ignored' the problems raised by the challenge of secularism and the spectacular rise of Pentacostalism in Brazil.] At the root was the superficial Christianization of the continent, which absorbed traditional Catholic practices into its culture far better than it did Christian doctrine itself.

That is why the Catholic mission there, as it is in the rest of the world, is 're-evangelization". Which is what Benedict is doing daily in trying to re-introduce the Christians of the world to Christ and to Christianity. That is where re-evangelization - or as it is now called, 'the new evangelization' - begins.

But you don't re-introduce Christ and Christianity in the misguided way the liberation theologians are doing - by making him out to be nothing more than a social activist, while ignoring, neglecting or even questioning his divinity. That is not simplifying Christ - that is falsifying him.

Through the centuries, hundreds of millions of simple folk cumulatively came to accept Christianity as it was taught to them, simply. As the Apostles did, simply: Christ is the Son of God, He is God's gift for the salvation for all men, and the Christian way of life is to love God, and love all men as one loves oneself. Benedict is settng an example for all Catholic priests on how to convey the message of Christ. Surely in time, it will have an effect.

The Protestant evangelists in Latin America have simplified their message too, not denying Christ's divinity, to begin with, but in ways that, as sociologists and historians and other scholars have studied, are able to get their message through somehow far more effectively and efficiently than the Roman Catholic Church. How lasting these 'conversions' will be, no one can tell yet...

In checking out some facts about religion on Brazil, I had turned to the APOSTOLIC VISIT TO BRAZIL thread in the Papa Ratzinger Forum - and found myself engrossed in rereading the whole thread - which began with preparations for that visit all the way through a full coverage of the visit itself and the major commentaries thereof. I needed to be reminded of the multifaceted richness, the breadth and depth, of that visit by Benedict XVI, in which he canonized Brazil's first native-born saint, Frei Antonio Galvao, and opened the Aparecida conference. But he also had an amazing encounter with the young people of Sao Paolo, which I shall resurrect here in connection with the current WYD Rio. Maybe he was thinking of that evening rally in Pacaembu Stadium when he decided tow years ago that the 2013 WYD would be held in Rio de Janeiro...

But I also came across his address to the bishops of Brazil in Sao Paolo Cathedral where he said, among his comprehensive checklist of the tasks for Latin American bishops, a number of things that resonate today under a new Pontificate, including the exhortation to bishops and priests to 'go to the outskirts', and starting with his citation of the Gospel passage that states the theme for this year's WYD, and goes on to anticipate the fundamentals he would seek to emphasize in decreeing the Year of Faith five years after that visit to Brazil:

"Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age" (Matthew 28:19-20).

These words are simple yet sublime; they speak of our duty to proclaim the truth of the faith, the urgent need for the sacramental life, and the promise of Christ's continual assistance to his Church.

These are fundamental realities: they speak of instructing people in the faith and in Christian morality, and of celebrating the sacraments. Wherever God and his will are unknown, wherever faith in Jesus Christ and in his sacramental presence is lacking, the essential element for the solution of pressing social and political problems is also missing.

Fidelity to the primacy of God and of his will, known and lived in communion with Jesus Christ, is the essential gift that we Bishops and priests must offer to our people (cf. "Populorum Progressio," 21).

Our ministry as Bishops thus impels us to discern God's saving will and to devise a pastoral plan capable of training God's People to recognize and embrace transcendent values, in fidelity to the Lord and to the Gospel.

Certainly the present is a difficult time for the Church, and many of her children are experiencing difficulty. Society is experiencing moments of worrying disorientation.

The sanctity of marriage and the family are attacked with impunity, as concessions are made to forms of pressure which have a harmful effect on legislative processes; crimes against life are justified in the name of individual freedom and rights; attacks are made on the dignity of the human person; the plague of divorce and extra-marital unions is increasingly widespread.

Even more: when, within the Church herself, people start to question the value of the priestly commitment as a total entrustment to God through apostolic celibacy and as a total openness to the service of souls, and preference is given to ideological, political and even party issues, the structure of total consecration to God begins to lose its deepest meaning.

How can we not be deeply saddened by this? But be confident: the Church is holy and imperishable (cf. Ephesians 5:27). As Saint Augustine said: "The Church will be shaken if its foundation is shaken; but will Christ be shaken? Since Christ cannot be shaken, the Church will remain firmly established to the end of time" ("Enarrationes in Psalmos," 103,2,5: PL 37,1353).

A particular problem which you face as Pastors is surely the issue of those Catholics who have abandoned the life of the Church. It seems clear that the principal cause of this problem is to be found in the lack of an evangelization completely centered on Christ and his Church.

Those who are most vulnerable to the aggressive proselytizing of sects - a just cause for concern - and those who are incapable of resisting the onslaught of agnosticism, relativism and secularization are generally the baptized who remain insufficiently evangelized; they are easily influenced because their faith is weak, confused, easily shaken and naive, despite their innate religiosity.

In the Encyclical Deus Caritas Est, I stated that "being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction" (No. 1).

Consequently, there is a need to engage in apostolic activity as a true mission in the midst of the flock that is constituted by the Church in Brazil, and to promote on every level a methodical evangelization aimed at personal and communal fidelity to Christ.

No effort should be spared in seeking out those Catholics who have fallen away and those who know little or nothing of Jesus Christ, by implementing a pastoral plan which welcomes them and helps them realize that the Church is a privileged place of encounter with God, and also through a continuing process of catechesis.

What is required, in a word, is a mission of evangelization capable of engaging all the vital energies present in this immense flock. My thoughts turn to the priests, the men and women religious and the laity who work so generously, often in the face of immense difficulties, in order to spread the truth of the Gospel.

Many of them cooperate with or actively participate in the associations, movements and other new ecclesial realities that, in communion with the Pastors and in harmony with diocesan guidelines, bring their spiritual, educational and missionary richness to the heart of the Church, as a precious experience and a model of Christian life.

In this work of evangelization the ecclesial community should be clearly marked by pastoral initiatives, especially by sending missionaries, lay or religious, to homes on the outskirts of the cities and in the interior, to enter into dialogue with everyone in a spirit of understanding, sensitivity and charity.

On the other hand, if the persons they encounter are living in poverty, it is necessary to help them, as the first Christian communities did, by practising solidarity and making them feel truly loved.

The poor living in the outskirts of the cities or the countryside need to feel that the Church is close to them, providing for their most urgent needs, defending their rights and working together with them to build a society founded on justice and peace.

The Gospel is addressed in a special way to the poor, and the Bishop, modelled on the Good Shepherd, must be particularly concerned with offering them the divine consolation of the faith, without overlooking their need for "material bread".

As I wished to stress in the Encyclical Deus Caritas Est, "the Church cannot neglect the service of charity any more than she can neglect the sacraments and the word" (No. 22)....

Starting afresh from Christ in every area of missionary activity; rediscovering in Jesus the love and salvation given to us by the Father through the Holy Spirit: this is the substance and lifeline of the episcopal mission which makes the Bishop the person primarily responsible for catechesis in his diocese.

Indeed, it falls ultimately to him to direct catechesis, surrounding himself with competent and trustworthy co-workers. It is therefore clear that the catechist's task is not simply to communicate faith-experiences; rather - under the guidance of the Pastor - it is to be an authentic herald of revealed truths.

Faith is a journey led by the Holy Spirit which can be summed up in two words: conversion and discipleship. In the Christian tradition, these two key words clearly indicate that faith in Christ implies a way of living based on the twofold command to love God and neighbour - and they also express life's social dimension.

Truth presupposes a clear understanding of Jesus's message transmitted by means of an intelligible, inculturated language, which must nevertheless remain faithful to the Gospel's intent.

At this time, there is an urgent need for an adequate knowledge of the faith as it is presented in the Catechism of the Catholic Church and its accompanying Compendium. education in Christian personal and social virtues is also an essential part of catechesis, as is education in social responsibility...

- BENEDICT XVI

Address to the Bishops of Brazil

Sao Paolo Cathedral

May 11, 2007

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 24/07/2013 11:00]