When I first read the story of Bishop Jin a few years back when he was featured in 30 GIORNI, I felt great admiration for someone who managed to be heroic and genuinely good, even if he had to pay lip service afterwards to the tyrants who had imprisoned him for 18 years and kept in a re-education camp for another 9 years. And he did it in order to keep the Church in Shanghai alive. That he was already 91 at the time of the 30 GIORNI report, and apparently still going strong, made his story even more remarkable. In my mind, he became the viable antithesis to Cardinal Joseph Zen, his fellow Shanghainese who has an unbending hard line against the Beijing government and insists, contrary to Benedict XVI's 1977 letter to Chinese Catholics, that the underground Church must remain underground in China until there is full religious freedom in China. IMHO, it took extraordinary courage to choose the option taken by Bisho, p Jin, who had surely earned the right to take the option (and gamble) that he did, having spent a third of his (very long) life in prison for his faith. Perhaps more Chinese bishops should take a lesson from his life, which seems to have been, at the very least, no less meritorious than the life of Cardinal Van Thuan, also imprisoned by the Communists in Vietnam and who is now a candidate for beatification.

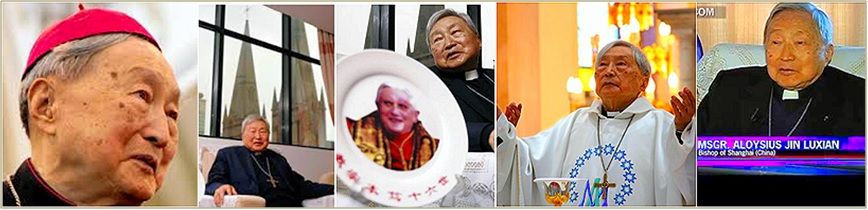

Pray for Aloysius Jin Luxian, 97:

When I first read the story of Bishop Jin a few years back when he was featured in 30 GIORNI, I felt great admiration for someone who managed to be heroic and genuinely good, even if he had to pay lip service afterwards to the tyrants who had imprisoned him for 18 years and kept in a re-education camp for another 9 years. And he did it in order to keep the Church in Shanghai alive. That he was already 91 at the time of the 30 GIORNI report, and apparently still going strong, made his story even more remarkable. In my mind, he became the viable antithesis to Cardinal Joseph Zen, his fellow Shanghainese who has an unbending hard line against the Beijing government and insists, contrary to Benedict XVI's 1977 letter to Chinese Catholics, that the underground Church must remain underground in China until there is full religious freedom in China. IMHO, it took extraordinary courage to choose the option taken by Bisho, p Jin, who had surely earned the right to take the option (and gamble) that he did, having spent a third of his (very long) life in prison for his faith. Perhaps more Chinese bishops should take a lesson from his life, which seems to have been, at the very least, no less meritorious than the life of Cardinal Van Thuan, also imprisoned by the Communists in Vietnam and who is now a candidate for beatification.

Pray for Aloysius Jin Luxian, 97:

The death of China’s

most famous and powerful bishop

by Anthony E. Clark, Ph.D.

April 30, 2013

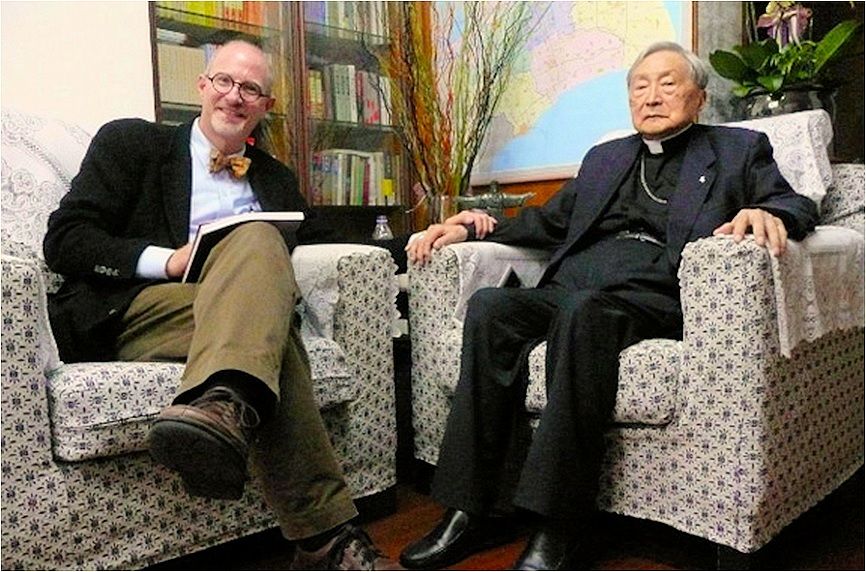

China’s most famous — and most powerful — Catholic bishop has died. He was 97. When I last saw him in 2011, I knew then that age was finally catching up with Shanghai’s remarkable and indefatigable prelate.

Jesuits in Shanghai, 1953: Bishop Ignatius Gong Pinmei is wearing a pectoral cross, and Fr. Jin stands to his right.

Jesuits in Shanghai, 1953: Bishop Ignatius Gong Pinmei is wearing a pectoral cross, and Fr. Jin stands to his right.

As we sat together, I handed him a pile of rare photographs of him and his fellow Jesuits, images that dated before his arrest in 1955. Pausing for some time as he looked over the first photograph, he said in a low voice, “Old beloved friends.” He had not seen those faces in more than six long and eventful decades.

He asked me to bring more photographs of “Catholic Shanghai before the Communists”; I do have more images to give him, but now he is perhaps seeing the real faces of his “beloved friends,” and I will file them away for posterity.

Bishop Aloysius Jin Luxian, SJ (1916-2013), was one of the most gentle and charming people I have met, and he was also among the most enigmatic, and as I thumb through his dossier I vacillate between admiration, disagreement, speculation, and sometimes disappointment.

As I said in my 2010 interview with Bishop Jin for Ignatius Insight, with Jin there are “no easy answers.” I would like to offer a few remarks here about why Bishop Jin’s recent death, at the age of 97, is probably one of the most noteworthy events in the history of Catholicism in China.

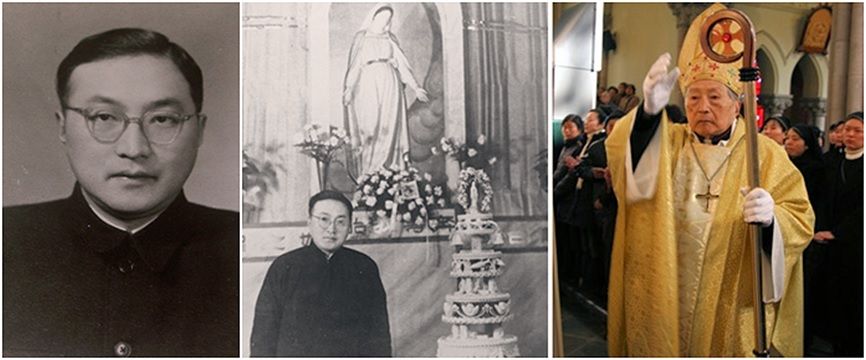

Left, Fr. Aloysius as a young Jesuit priest in the 1940s; center, at his birthday celebration in Shanghai (1954); right, Bishop Jin Luxian at the celebration Mass commemorating 400 years of Catholicism in Shanghai in 2008.

Left, Fr. Aloysius as a young Jesuit priest in the 1940s; center, at his birthday celebration in Shanghai (1954); right, Bishop Jin Luxian at the celebration Mass commemorating 400 years of Catholicism in Shanghai in 2008.

Jin Luxian lived through China’s most dramatic changes and growing pains as it transitioned from empire to the largest and most paradoxical Communist country in the history of our world.

He witnessed China’s war with Japan (1930s); the fierce and tragic war between his own countrymen, the Nationalists and Communists (1920s-1949); the rise of Mao Zedong and Maoism in 1949; the turbulent 100 Flowers Movement (1956) and the following Anti-Rightist Campaign (1957-1958); the Great Leap Forward and the millions of deaths it caused (1958-1961); the cruel violence of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976); the post-Mao economic boom inaugurated by Deng Xiaoping (1989-present).

This long list of China’s landmark events does not include equally dramatic events in Catholic history, such as the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965). Because he was a Jesuit priest who had earned his doctorate in theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, Jin was labeled a “dangerous counter-revolutionary” in alliance with an “imperialist power,” the Vatican.

Jin Luxian’s life provides historians extraordinary access to some of the world’s most exceptional moments of transformation, and if you ask China’s Catholics who has been the most influential figure in their Church’s remarkable survival and seemingly-impossible growth through their country’s painful birth as a Communist superpower, they will, to the person, reply, “Bishop Jin.”

On my desk as I write this essay lie two handsome photo-histories of the Diocese of Shanghai, replete with images of Bishop Jin, as well as a massive 750-page collection of his homilies, a French biography of his life (

Le Pape Jaune: Mgr. Jin Luxian, Soldat de Dieu en Chine Communiste (The Yellow Pope: Bishop Jin Luxian, Soldier of God in Communist China), countless Chinese liturgical books that he has either written himself or sponsored, and the recently-published copy of his personal memoirs, to which I wrote the introduction.

Books by or about him can fill a bookcase, and anyone who has made a tour of “Catholic Shanghai” cannot but notice that Bishop Jin singlehandedly solicited enough funds from all over the globe to restore Shanghai’s numerous churches, build a new seminary, and commission the construction of many other Catholic facilities, including a busy retreat house for China’s overworked clergy. Catholic Shanghai is Jin’s Shanghai, and his new rectory towers over his cathedral, named after St. Ignatius, the founder of his order.

Many Catholics have asked; how did Bishop Jin manage to build a Catholic empire in Shanghai under the watchful eye of a Communist government that had vowed to “help religion along the natural path of withering away”?

I once asked him how he explained his successful efforts to revitalize the Church in China while also maintaining a cozy relationship with the Communist Party.

He answered: “I am both a serpent and a dove. The government thinks I’m too close to the Vatican, and the Vatican thinks I’m too close to the government. I’m a slippery fish squashed between government control and Vatican demands.”

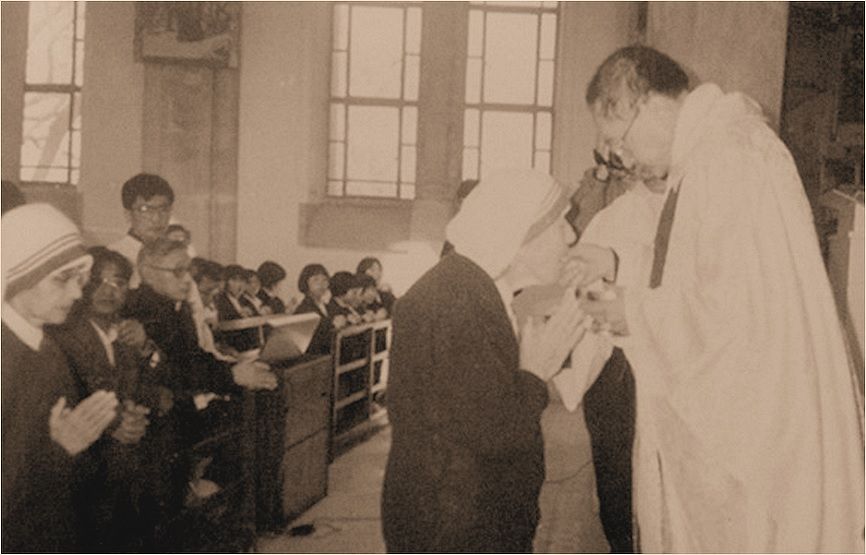

For better or worse, Bishop Jin Luxian’s priority was the survival of Catholicism in China, and he maintained connections with an enormous array of personalities. He kept a wide range of company; in one photograph he is pictured at Rice University with his friend, the dissident theologian Hans Küng, in another he is seen giving Holy Communion to Mother Teresa, and in yet another photo Jin is shown meeting with President Bill Clinton.

Bishop JIn administers Communion to Mother Teresa, 1993.

Bishop JIn administers Communion to Mother Teresa, 1993.

While there can be little doubt that he was able to use his connections to preserve and promote the Church in China, Jin’s decisions were not always popular with Rome.

When he accepted his office as bishop of Shanghai in 1988, he did so without the approval of the Holy See. In his “Acceptance of Office and Promise of Fidelity,” Bishop Jin pronounced, “I believe all the teachings on faith in the Holy Church…I will try my best to take care of the spiritual and material needs of the clergy and faithful.” And then he promised to “observe the Constitutions and Laws of the People’s Republic of China,” and offer his life for God and the “independent and autonomous Diocese of Shanghai” (Jesuit Archives of Taipei, Jin Luxian File).

While rendering his obedience to the Constitutions and Laws of the Communist government of China, he was at the same time writing countless letters to foreign bishops, describing the political persecution under which Chinese Catholics suffer, and asking for generous donations to rebuild the Chinese Church.

One of his patent lines in letters to solicit even a small donation was, “Many streams make a large river” (Jesuit Archives, Taipei: letter to Cardinal Jaime L. Sin [1928-2005], January 19, 1997). I cannot help but have mixed feelings knowing that Jin made public concessions to China’s oppressive and anti-religious government, while at the same time I know I am kneeling in prayer in a Shanghai church that was funded and restored through Jin’s efforts.

Even as one considers Jin Luxian’s collaboration with China’s authorities and the Communist-overseen Catholic Patriotic Association, anyone with sympathy for human suffering must acknowledge his herculean resolution to survive decades of sustained Communist imprisonment, bullying, and “re-education.”

In the 1950s, Shanghai’s Party officials launched a merciless attack against the city’s popular bishop, Ignatius Gong Pinmei (1901-2000). On the evening of September 8, 1955, the Shanghai police made a wide sweep through the city’s Catholic residences.

Father Jin was at home reading a book at 9:30 pm, when plain-clothed officers forced themselves into his room and arrested the unsuspecting priest. As he recalled his arrest: “The Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary was 8 September 1955, which was also the anniversary of my vows” (Memoirs [Hong Kong: 2012], 206).

He was rebuked, as was his fellow prisoner, Bishop Gong Pinmei, as a “stinking old nine intellectual” and a “parasite” of the People. He began his tireless work to restore the Church in China after his release from prison, when he was 66 years old, and he adhered to the Jesuit motto, 'Magis' (more)—until his death a few days ago, at the age of 97.

In the preface of his Memoirs, which he wrote when he was 92 years old, Bishop Jin wrote: “When I close my eyes and think back, those years have truly passed in an instant, but on close examination this instant was full of hardship” (Memoirs, 1).

Whether or not his methods were correct—only God is the rightful judge of souls —

his life was not one of comfort and selfishness; Jin Luxian, if anything, lived as a Catholic priest.

There is much about Bishop Jin’s actions that many loyal Catholics may not comfortably condone, but none of us is without sin and complexity. Every time we met, Jin was unselfish with his time, and spoke with warmth and kindness.

As I wrote in my introduction to his Memoirs, “Jin Luxian has been identified as a politician, protector, and prisoner, but he would simply refer to himself as a priest; and in a final word, Jin as always been, and remains, a priest” (Memoirs, xx).

There is little doubt that the Church in China has flourished under his leadership, as priest, bishop, and administrator. One of his favorite sayings of St. Ignatius, the holy founder of the Jesuits, was, “Oportet illum crescere, me autem minui”—“He should grow and I should diminish.”

Bishop Jin has gone, but I suspect that his greatest wish would be for the Church he left behind to continue to grow, even as his memory diminishes into history.

Requiem ætérnam dona eis; et lux perpetua lúceat eis.

The author of the article with Bishop Jin at his private residence in Shanghai, 2011.

The author of the article with Bishop Jin at his private residence in Shanghai, 2011.

Three days after Bishop Jin's death, the Vatican Secretariat of State released this statement (translated by the English service of VatiCan Radio):

NOTE FROM THE SECRETARIAT OF STATE

ON THE DEATH OF BISHOP JIN LUXIAN

On Saturday, April 27, His Excellency Mons. Aloysius Jin Luxian S.J., Coadjutor bishop of Shanghai (continental China), passed away at the age of 96.

The Prelate was born on June 20, 1916 in the Nanshi district in the city of Shanghai. In September 1926 he began his primary school studies at Saint Ignatius College; then, in 1932, he entered Sacred Heart of Jesus seminary, and later attended the Sacred Heart of Mary major seminary.

Attracted to the spirituality and life of the Society of Jesus, in 1938 he began his novitiate, and on September 8, 1940 he made his first vows. Having concluded his studies in philosophy and theology at Xianxian (Hebei), he was ordained to the priesthood on May 19, 1945 in the cathedral of Shanghai.

Between 1947 and 1948 he completed his religious formation in Paris. Then, from 1948 to 1950, he attended the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome where he received a degree Theology. He spent his summer vacations in Germany, France, and England in order to learn the respective languages.

With the advent of the People’s Republic of China, he was called to return to his native country in 1950 and, following the political events at that time and the expulsion of foreign Jesuits, he was nominated the temporary rector of the regional seminary of Xuhui (Shanghai) in 1951.

Fr Jin Luxian was arrested the night of September 8, 1955. and was subject to a long interrogation, ending with a trial in 1960: he was sentenced to 18 years in prison, plus 9 years for rehabilitation.

From 1963 to 1967 he was detained at Qincheng prison in Beijing where, by reason of his considerable knowledge of foreign languages, was made part of a group of inmate translators who worked for the State. In 1967 he was transferred to the rehabilitation centre in Fushun and in 1973 to another in Qincheng where he remained until 1975. He was then sent to a labour camp in Henan, and imprisoned again from 1979 to 1982: he was released after 27 years in prison.

In 1982 he received permission to reopen the seminary in Sheshan. In 1985 Fr Jin Luxian agreed to be consecrated bishop for the Diocese of Shanghai, but without papal approval. He obtained approval some 15 years later, becoming the coadjutor bishop of Shanghai, after having shown his fidelity to the Pope and asking pardon for his illegitimate ordination.

The prelate was a key personality in the history of the Catholic Church in China over the last 50 years. He was a man of great culture. His preparation, his studies in Italy, his proficiency in various European languages and his human compassion allowed him to keep in contact with various personalities and enjoy the respect of many.

Under the leadership of Bishop Aloysius Jin Luxian, the diocese of Shanghai developed a great deal. He had a powerful pastoral commitment, modernizing the dioceses in many ways and trying to ensure they remained under the leadership of the pastors, using also to this end the respect which the civil authorities had for him.

He was particularly attentive to the preparation of new priests and religions, launching proper formation facilities, such as the Major Seminary, opened in 1985 in Sheshan (Shanghai), and giving back, at the same time, a greatly appreciated service not only to his dioceses, but also to China.

In one of his final acts as bishop Jin wrote the pastoral letter on the occasion of the Chinese Year of the Dragon (January 23, 2012) with the title “Xu Guangqi: A Man for All Seasons.”

In it the Prelate invited the faithful to follow the example of Paul Xu Guangqi, the first high-ranking Catholic in the empire, friend of Fr. Matteo Ricci, by promoting the cause for his beatification.

There are 150,000 Catholics in the diocese of Shanghai, some one hundred priests, six deacons, 37 parishes, and 140 churches. In its territory is the Marian Shrine of Sheshan, a national pilgrimage site. The most important social institutions include the house for the elderly, a house for spiritual retreats, a soup kitchen, and the Typography of Qibao.

In 2012 Bishop Jin published the first volume of his memoirs, Learning and Re-learning 1916-1982, in which he recounts the most significant times in his life. A life in which he sought to keep the love of Christ and the Church alive, in loyalty to his country and culture.

I must confess I was perplexed that there was not a statement or telegram of condolence from Pope Francis, considering that Bishop Jin was Jesuit like him, and that he was an extraordinary figure in the history of the Church in China, indeed of the Church in the 20th century.

Shanghai bishop's funeral held

as his anointed successor continues

to be detained by the Chinese

BEIJING, May 2, 2013 (AP) - Funeral services were held on Thursday for Shanghai Bishop Aloysius Jin Luxian, while the whereabouts of his anointed successor remained unclear amid a struggle for control between the Vatican and the ruling Communist Party.

Bishop Jin died on Saturday at age 97, leaving deep uncertainty about the future leadership of one of China's largest and wealthiest dioceses. His successor, Bishop Thaddeus Ma Daqin, was placed under house arrest last year immediately after he renounced his role in the Communist Party-controlled Catholic Patriotic Association.

Bishop Ma had been confined to Shanghai's main seminary at Sheshan, but reportedly was moved recently to an undisclosed location.

The officially atheist Communist Party insists on tightly controlling all organised religions. It requires that Catholics worship in churches that belong to the Patriotic Association and demands the right to appoint bishops in defiance of the Vatican.

Despite that, Bishop Ma had been approved by both the Vatican and Beijing, making his public renunciation of the Patriotic Association at his July 7 ordination Mass a grave affront to the party.

Security was tight for Bishop Jin's funeral, with dozens of uniformed and plainclothes police officers on hand. Six officers kept a close eye on those lining up for flowers to place on Bishop Jin's bier, turning away journalists and others on an unofficial blacklist.

Despite that, more than 1,000 people filled a large hall dominated by a big portrait of Bishop Jin, about the same number who attended a funeral mass at the city's St Ignatius Cathedral earlier in the week.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 03/05/2013 15:05]