Here are two snapshots in time of the 'adaptable' and possibly opportunistic attitudes of NCReporter's John Allen towards Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI from the time he wrote a generally negative 'biography' of him in 2005, to tWO dayS after his inaugural Mass as Pope, which is when he wrote the first article posted here.

Here are two snapshots in time of the 'adaptable' and possibly opportunistic attitudes of NCReporter's John Allen towards Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI from the time he wrote a generally negative 'biography' of him in 2005, to tWO dayS after his inaugural Mass as Pope, which is when he wrote the first article posted here.

4/26/05

On this day, John Allen went on record to show his changing attitudes towards Cardinal Ratzinger and his prospects of becoming Pope and why.

Pondering the first draft of history

4/26/05

On this day, John Allen went on record to show his changing attitudes towards Cardinal Ratzinger and his prospects of becoming Pope and why.

Pondering the first draft of history

by John Allen Jr.

'The Word from Rome'

April 26, 2005

In the immediate aftermath of the election of Benedict XVI, several readers wrote, not without a tinge of

schadenfreude, to remind me that in May 2002 I wrote a column predicting that Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger would not be elected pope. Others pointed out that in my "Top 20" papbile list posted on the

National Catholic Reporter's Web site before the Conclave, Ratzinger's name did not appear.

So, let me acknowledge, publicly and clearly, that I did not predict this.

In my defense, however, I would note that in my revised 2004 edition of

Conclave, I listed Ratzinger among the candidates to watch.

Moreover, in an April 14 story for the NCR Web site, four days before the opening of the conclave, I wrote the following: "The push for Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the pope's doctrinal czar for 24 years and the dean of the College of Cardinals, is for real. There is a strong basis of support for Ratzinger in the college, and his performance in the period following the death of the pope, especially his eloquent homily at the funeral Mass, seems to have further cemented that support. One Vatican official who has worked with Ratzinger over the years said on April 13, 'I am absolutely sure that Ratzinger will be the next pope.'"

On April 16, two days before the conclave, I wrote: "Despite the nonstop speculation surrounding the conclave that opens April 18, the press seems to have at least one thing right: In the early stages, the balloting will likely shape up as a 'yes' or 'no' to the candidacy of German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger."

Hence I was not quite as off-key as some of my earlier writings might suggest. Nevertheless, it remains true that, like most commentators, my judgment was colored by some of the old bits of conventional wisdom about papal elections: that he who goes in a pope, comes out a cardinal (now false in three of the last six elections); that the 76 percent of the cardinals who are residential [diocesan bishops] would not elect a curial candidate; that a man too closely identified with the policies of the previous pontificate would not be elected; that 78 was too old. All of that, it turns out, was hogwash.

Having spoken with a number of cardinals after the election,

it seems clear to me that I and most of my colleagues simply over-analyzed this election. We thought in terms of geographical blocks, political interests, and public relations concerns;

the cardinals, it seems, just asked themselves who among them was the best man for the job and voted accordingly. The fact that it didn't take them long suggests it did not strike them as an exceptionally difficult judgment to make.

As I said many times in lectures and on television when asked about Ratzinger, whatever you make of his theological positions, there's no question the man has everything you'd want in a pope: intellect, experience, integrity, deep spirituality, a gift for languages, and a sense of the universal church. Moreover, the list of such men in the College of Cardinals was not especially long.

I suppose the major reason I entertained doubts about Ratzinger as a

papabile is what might be called the "baggage" factor. Fairly or unfairly, in some Catholic circles Ratzinger is a lightning rod, a beloved hero among conservatives and something of a Darth Vader figure for Catholic progressives. I wondered if the cardinals would want to elect as pope someone who brought with them that kind of profile.

Every journalist covering the Vatican to some extent reflects the limitations of his or her own nationality and cultural experience, and on this point, in hindsight, I see how much of an American I was. In Africa, Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe, Ratzinger has no such profile, except in very restricted theological circles. Cardinals from those parts of the world did not bring such concerns.

It's really only in pockets of Western Europe and North America that the broader Catholic public had any sense of the man prior to his election, explaining why

some of the initial reservations about Ratzinger's candidacy came from American and German cardinals.

In the end, they too seemed persuaded that the man the world would know as Benedict XVI would not match the public profile sometimes associated with Ratzinger, whom I once dubbed "the Vatican's enforcer."

On this score, it may be that the cardinals had better instincts than I did. A CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll of American Catholics conducted shortly after the white smoke came up from the Sistine Chapel found that 31 percent had a favorable reaction to the new pope, 9 percent unfavorable, and almost 60 percent said they didn't have enough information to reach a conclusion. In other words,

more than 90 percent of American Catholics already like the pope, or at least are willing to give him a chance. That's considerably less baggage than I might have guessed.

Still, nine percent of America's 65 million Catholics amounts to roughly 5.8 million people, which is a large pocket of opposition right out of the gate. Those numbers have been mirrored in polls across Western Europe. Obviously, Pope Benedict is aware that some Catholics have trepidations about where his papacy will go, and he has been at pains in the early days to calm anxieties.

In his programmatic talk on Wednesday morning, April 20, following Mass with the cardinals in the Sistine Chapel, he talked about dialogue, ecumenism, inter-religious outreach, the need for the church to witness to authentic social development, and

his desire to transmit joy and hope to the world.

On Monday, April 25, in an audience with representatives of other religions, the pope said: "At the beginning of my pontificate I address to you, believers in religious traditions who represent all those who seek the truth with a sincere heart, a strong invitation to become together artisans of peace in a reciprocal commitment of comprehension, respect and love."

Make no mistake: the pontificate of Benedict XVI will be dramatic, and it will not always be comfortable for Catholics with views that might conventionally be described as "liberal" on matters of sexual morality, theological dissent, or authority in the church.

At the same time, Pope Benedict is known as a man of deep intelligence and profound love for the church, and to date there's no evidence that he intends to launch a new anti-modernist purge. (That hasn't stopped some gleeful partisans from drawing up their own enemies lists, but it's too early to know what will come of all this).

My own sense is that Benedict is a pope who may surprise all of us. Whichever way the pontificate goes, it will be fascinating to watch.

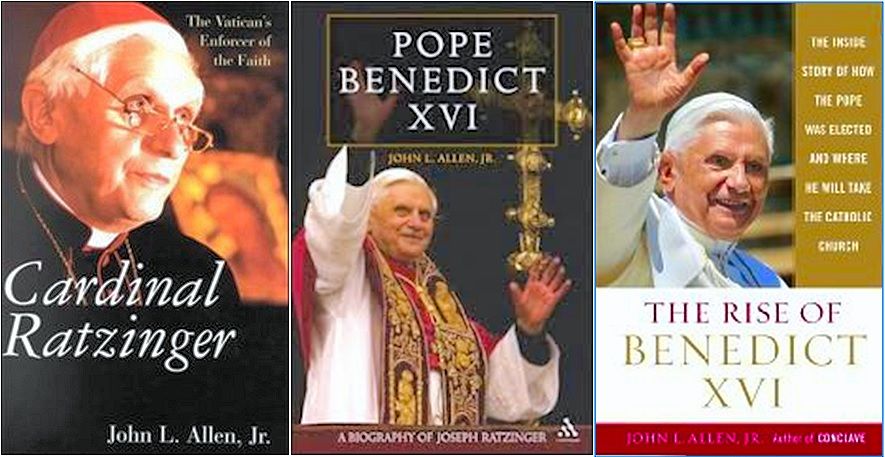

Six years ago, I wrote a biography of the man who is now pope titled

Cardinal Ratzinger: The Vatican's Enforcer of the Faith. In the intervening period, I have learned a few things about the universal Catholic church and how things look from different perspectives.

If I were to write the book again today, I'm sure it would be more balanced, better informed, and less prone to veer off into judgment ahead of sober analysis.

This, I want to stress, is not a Johnny-come-lately conclusion motivated by the fact that the subject of the book has now become the pope. In a lecture delivered at the Catholic University of America as part of the Common Ground series, on June 25, 2004, I said the following about the book:

"My 'conversion' to dialogue originated in a sort of 'bottoming out'. It came with the publication of my biography of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, issued by Continuum in 2000 and titled

The Vatican's Enforcer of the Faith.

"The first major review appeared in

Commonweal, authored by another of my distinguished predecessors in this lecture series, Fr. Joseph Komonchak. It was not, let me be candid, a positive review.

Fr. Komonchak pointed out a number of shortcomings and a few errors, but the line that truly stung came when he accused me of 'Manichean journalism.' He meant that I was locked in a dualistic mentality in which Ratzinger was consistently wrong and his critics consistently right. I was initially crushed, then furious. [NB: Yet during Benedict XVI's Pontificate, Fr. Komonchak was often volubly critical of Benedict XVI's reading of Vatican II!]

I re-read the book with Fr. Komonchak's criticism in mind, however, and reached the sobering conclusion that he was correct. The book - which I modestly believe is not without its merits - is nevertheless too often written in a "good guys and bad guys" style that vilifies the cardinal. It took Fr. Komonchak pointing this out, publicly and bluntly, for me to ask myself, 'Is this the kind of journalist I want to be'?

My answer was no, and I hope that in the years since I have come to appreciate more of those shades of gray that Fr. Komonchak rightly insists are always part of the story.

After Ratzinger's election as Benedict XVI was announced, I had hoped to have the opportunity to write a new preface for the book contextualizing some of the views it expresses. Unfortunately, the publisher in the United States, for reasons that I suppose are fairly obvious, had already begun reprinting the book without consulting me. Hence it is probably already appearing in bookstores, without any new material from me.

I can't do anything about that, although the British publishers were kind enough to ask me to write a new preface, which I have already done, so at least the damage will be limited in the U.K.

What is under my control, however, is a new book for Doubleday (a Random House imprint), which I hope will be a more balanced and mature account of both Ratzinger's views and the politics that made him pope. It has been in the works for some time and I hope it will be worthy of the enormity of the story, and the trust of those who elect to read it.

Quite an admission, and my comment at the time was: "Hats off to a rare journalist who admits that he was wrong and changed his ways"... Well, the change did not last beyond 3, at most 4 years, with respect to Benedict XVI...

The three versions of Allen's 'biography' of Joseph Ratzinger.

Some time last year (2012), I came across this article online - which I had not seen before - while googling something else, and I thought it would make excellent Good Friday reading in a certain sense. But I somehow never found appropriate the opportunity to post it: In 2000, Fr. Vincent Twomey, who obtained his doctorate in theology at the University of Regensburg under Prof. Joseph Ratzinger, reviewed John Allen's 'biography' of Joseph Ratzinger, and gives us a very good idea of where Allen is coming from, bearing in mind that he appeared to have about 3-4 years of reversing his 2000 biases after his subject became Pope, after which he reverted to form, either because he really feels negatively about Joseph Ratzinger and/or because he is playing to the type of CINOs who read the newspaper he writes for...

A question Of fairness:

The three versions of Allen's 'biography' of Joseph Ratzinger.

Some time last year (2012), I came across this article online - which I had not seen before - while googling something else, and I thought it would make excellent Good Friday reading in a certain sense. But I somehow never found appropriate the opportunity to post it: In 2000, Fr. Vincent Twomey, who obtained his doctorate in theology at the University of Regensburg under Prof. Joseph Ratzinger, reviewed John Allen's 'biography' of Joseph Ratzinger, and gives us a very good idea of where Allen is coming from, bearing in mind that he appeared to have about 3-4 years of reversing his 2000 biases after his subject became Pope, after which he reverted to form, either because he really feels negatively about Joseph Ratzinger and/or because he is playing to the type of CINOs who read the newspaper he writes for...

A question Of fairness:

A review of John Allen's

'biography' of Cardinal Ratzinger]

Fr. Vincent Twomey, SVD

Issue of October 2001

Cardinal Ratzinger is perhaps the most controversial figure in the Church today, a subject awaiting an author. Various articles about him have appeared, but no book, until the recent appearance of that by John L. Allen, Jr., Vatican correspondent for the National Catholic Reporter.

Is it fair to Ratzinger? As a former student of the Cardinal, I must admit to having some serious misgivings.

This book,

Cardinal Ratzinger: The Vatican's Enforcer of the Faith (Continuum, 2000), is a strange mixture, part early biography (ch. 1-3), part chronicle of some major controversies (4-6), part judgment on Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger's performance as "enforcer of the faith" and his chances at becoming future Pope (7-8).

Towards the end of the book, Allen describes the Cardinal as "in most ways the best and brightest the Catholic church of his generation has to offer, a musician and man of culture, a genteel intellectual and polyglot, a deep true believer" (p. 313).

Yet, Allen adds,

he has left in his wake a fractured Church.

[How is it that one cardinal among 200 or so could wreak so much havoc as to 'leave behind a fractured Church'? It seems to be assigning too much influence on Cardinal Ratzinger simply to be able to turn around and blame him singlehandedly for 'a fractured Church'!]

The "yet" (or its equivalent) well typifies Allen's account of Ratzinger's position on various theological and ecclesiastical issues, which is

often concise, though lacking any great depth or insight, but in the final analysis is negated by some "fault" or other.

In his concluding chapter, he also offers his readers a succinct summary of the main points of what he considers to be of enduring value that remained with him after reading Ratzinger for over a year (pp. 303-6). Anyone skeptical of Allen might first read this to be assured of his good faith.

So too, Allen's accounts of various major controversies, in particular the chapter on liberation theology, are invariably interesting.

How accurate they are is another matter, but the author generally tries to be fair and balanced. The crucial question is: to what extent does he succeed?

For Ratzinger, in the final analysis, remains for Allen the bogeyman that frightens most liberals,

the main source of division and demoralization in the contemporary Church. He is the power-wielding churchman whose later theological views, in contrast with his earlier "liberal" stance, has had the effect, inter alia, of "legitimizing the concentration of power in the hands of the Pope and his immediate advisors in the Roman curia" (p. 309).

In other words, despite all his efforts to be fair, and Allen does make considerable efforts in that direction, the Cardinal remains the ogre.

Take, for example, Allen's account of the liberation theology saga culminating in its effective defeat as a result in large measure of Ratzinger's theological analysis, and, more importantly, it is claimed, his ecclesiastical, political machinations.

This account is not without its merits, but

one's confidence in Allen's historical judgment is placed under severe strain, when

he blames the Cardinal for the failure of Latin American Catholicism to create a social order that better reflects gospel values, namely less inequality between rich and poor(cf. p. 173). [Imagine that! John Paul II visited Latin America 16 or 18 times and everyone has been raving about his preferential option for that continent compared to Benedict XVI's 'neglect' once he became Pope. And now it turns out that Allen blames Cardinal Ratzinger, again singlehandedly, for the abject failure of Latin American Catholicism. My goodness! Was there ever a Church statesman who had such singlehanded power not just over the universal Church but even over the fate of a huge continent?]

One could reasonably argue that more might have been accomplished at the political level in Latin America, if liberation theologians had at the outset not been so skeptical of either Catholic social teaching or the political potential of indigenous cultural traditions of piety they later rediscovered, but that is another issue.

Allen claims that

Ratzinger's attitude to other religions is negative, yet he fails to note, for example, that the Patriarch of Constantinople awarded Professor Ratzinger the Golden Cross of Mount Athos for his contribution to a greater understanding between Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

Later on, as Cardinal, he joined his former students at the Orthodox center near Geneva for a most amicable and fruitful discussion with representatives of the Greek Orthodox Church, whose tradition he frequently cites.

Allen seems not to know anything about the Cardinal's role in helping to establish diplomatic relations between the Vatican and Israel. And not a word is heard of his defense of Islam from the blanket charge of fundamentalism (cf. A Turning Point for Europe?, p.165-70) or his appreciation of the significance of primordial religious rituals and myths, as found, e.g. in the Hindu tradition (cf. ITQ 65/2, 2000, 257).

But it is above all in Allen's attempt to write a life of Cardinal Ratzinger (ch. 1-3), that the distorting effect of what seems to be the liberal's underlying fear of the bogeyman can be seen. The main tendency in these opening chapters, it would appear, is

to find an explanation for the transmutation into the "enforcer of the faith" of the earlier "liberal" Ratzinger, the young and promising theologian, who as peritus to Cardinal Frings, played such an important role at the Second Vatican Council.

Joseph Ratzinger grew up in the shadow of Nazi Germany within a family that was decidedly anti-Nazi and a Church that was hostile to Hitler — though perhaps not as publicly defiant as a later generation, that did not live in those circumstances, might claim that it should have been.

[It's exactly the attitude of those who criticize Pius XII for his prudence and discretion in World War II. What would they have done if they had lived under the Nazis as the Ratzingers did, or forcibly with the Nazis, as the Pope had to do?]

That experience undoubtedly had an influence on Ratzinger, as he himself expressly said. But the claim that

"Ratzinger today believes that the best antidote to political totalitarianism is ecclesial totalitarianism" (p. 3),

however appealing as a sound bite, does not stand up to scrutiny.

DIM=8pt][Ah, but that is Allen's stock-in-trade: he is always ready to sacrifice common sense or even truth for the sake of what he thinks to be a clever sound bite! (Including those inappropriate colloquialisms that I have often remarked upon). And you can almost see him rubbing his hands is smugly, saying to himself, "What a clever boy I am!"] It is, however, the leitmotif of the whole book.

According to Cardinal Ratzinger himself, on the contrary, the best antidote to totalitarianism is the upright conscience typically associated with the poor and the weak (cf. Church, Ecumenism and Politics, p. 165-80). And

the role of the Church, he once affirmed, is primarily educational — understood in the spirit of the Greek philosophers who sought" . . . to break open the prison of positivism and awaken man's receptivity to the truth, to God, and thus to the power of conscience . . . " (A Turning Point for Europe?, p. 55).

[Something he recently restated very powerfully in Cuba.]

Though of central importance to Cardinal Ratzinger, both as a man and as a theologian, the primacy of conscience is not even mentioned by Allen.

More serious are insinuations about the supposed failure of Ratzinger's own family to show more overt opposition to Nazi terror. Such a judgment shows little understanding of what living in a reign of terror involves, especially for a policeman and his young family (one is reminded of the film

Life is Beautiful).

Failing to note the fleeting and sketchy nature of such recollections, and unaware of other autobiographical references to that time (cf., e.g., Dolentium Hominum, no. 34,1997, p. 17), Allen claims that Ratzinger tends to be selective in his own memory of those times.

To prove that Ratzinger's positive appraisal of the role of the Catholic Church at the time was "one-sided and even distorted in its emphasis on the moral courage of the church,

at the expense of an honest reckoning with its failures" (p. 30), Allen claims that "Hitler came to power on the back of Catholic support" (p. 27).

This is a serious misinterpretation of events. Allen gives no source for this or similar doubtful interpretations of events. (Indeed, his failure to give his sources is a major weakness of the book.) [And the abiding maddening vice of Vaticanistas who deal too often and too much in speculation, rather than facts, and end up citing never-named 'informed sources' to speak out the reporter's own biases.]

It would seem that here Allen is following some very biased reading of the historical events. But the reader is left with the vague, overall impression that Cardinal Ratzinger must be hiding something, or at least temporarily repressed it. And so,

a shadow is cast over his youth in preparation for the emergence of the full-blown ogre in later life.

It is a cliche in popular theological circles to distinguish between the early and the late Ratzinger. He himself maintains that there is a basic continuity in his theology, a continuity that is not inconsistent with significant changes in perspective, even at times contradicting isolated claims he made in his theological youth.

He has acknowledged, for example, a significant development in his eschatology. After all, "[T]o live is to change . . . " Is it too much to suggest that the changes in his thinking might best be interpreted as signs of maturity, of further reflection due to changing circumstances and broader experience, especially as Prefect of the Congregation?

His youthful enthusiasm for collegiality, for example, led to a reappraisal of the institution of national Episcopal Conferences in the light of his own personal experience in such conferences and as a result of his further theological reflection. He also noted the failure of the German bishops during the Nazi period to act more decisively and effectively because of collective responsibility.

Instead, Allen attributes a radical change from "erstwhile liberal" to the conservative "enforcer of the faith" to four causes: the 1968 student unrest, perceptions of decline in church attendance and vocations, too much exposure to Catholic faith at its most distorted, and, finally, power.

The student unrest in the late '60s did have a profound effect on anyone who lived through that turbulent period, and he himself has on occasion referred to this, though it seems to me that his reflections on this period make use of ideas he had already formed in his earlier writings.

It is doubtful if the decline in church numbers could have had such a radical effect on him. At a discussion of precisely this topic during a meeting of his former students, he once remarked that the sin for which David was most severely punished by the Lord was not his adultery or the murder of Bathsheba's husband, but the census, the king's attempt to number the people of God.

Thirdly, his exposure as Prefect to the "pathology of the faith," as Allen calls it, is more than offset by his own wide reading in the Fathers, contemporary theology, and philosophy, not to mention literature.

His scholarly disposition to read and research finds due expression in various scholarly and general publications, the most recent being

The Spirit of the Liturgy earlier last year (also not mentioned by Allen).

And so one is left with the final "cause": power.

To suggest that the lust for power played a central role in any supposed "change of heart" that Professor Ratzinger revised his theology to advance his career, is (to put it mildly) mistaken, since his theological shift was manifest long before he went to Rome.

It should be mentioned that Ratzinger was never a student of Rahner, as Allen, quoting Wiltgen, claims. Nor was his move to Regensburg made in order to separate himself "intellectually from hitherto close colleagues like Kung and even his old ally, Rahner," as Adrian Hastings in a review of this book claims. Rahner at the time was at Munster, not Tubingen.

The main reason for Ratzinger's decision to leave such a prestigious university was to escape the turmoil among students and on the faculty in Tubingen, and thus be able to devote himself completely to scholarship in his native Bavaria.

This was told to me by Professor Kevin McNamara, Maynooth, in 1970 — information that led to my going to Regensburg for postgraduate studies instead of Tubingen. Later, some of Ratzinger's doctoral students and assistants at Tubingen confirmed this. (He also had personal, more familial reasons.)

Incidentally, Rahner was invited by Ratzinger to be a guest speaker at one of the end-of-semester doctoral colloquia in Regensburg. To the best of my knowledge, their theological differences (which were profound) predate Ratzinger's appointment to Tubingen. Such differences did not dull his respect for Rahner.

His so-called "change of heart" in theology, it is claimed, is reflected in the two Schulerkreise (not Studentenkreise, the term Allen uses) he is supposed to have built up: those from his years in Bonn, Munster, and Tubingen, and those from his years in Regensburg,

"the latter group theologically at odds with the former" (p. 104). This division "underlines the gap between Ratzinger before and after the Council." I am mentioned as an example of the latter group.

Allen seems to have conducted fairly extensive interviews with

two students of the "earlier Ratzinger," but only spoke briefly on the phone to one of the "later Ratzinger", Fr. Joseph Fessio, S.J. Considering the number of postgraduate students who studied under Ratzinger (somewhere between 40 and 50), this is slim evidence on which to base such a far-reaching thesis.

It is a pity that the author did not consult the comprehensive report on the doctoral colloquium and the later Schulerkreis by his former Assistant, Professor Stephan O. Horn, SDS (cf. Alla scuola della Verita, Milan, 1997, pp. 9-26).

Allen is wrong on several details, such as describing me as a spokesman for the Archbishop of Dublin (untrue) and citing extracts from my writings, especially that from my thesis, without any regard for the context.

And he erroneously makes Cardinal Schonborn a student of Ratzinger's, devoting several pages to the present Archbishop of Vienna to illustrate the "later Ratzinger" (

While a visiting scholar in Regensburg, Schonborn joined our colloquium for two semesters, as did other visitors. It was only after Ratzinger's elevation as Archbishop of Munich, that Schonborn became one of a number of regular guests at the annual meetings of the Schulerkreis.

It is, further, misleading to say that Ratzinger "built p" two distinct circles of students. There was never more than one, though its composition evidently changed with its members. Indeed, some of his students from his time in Bonn, Munster, and Tubingen might well be considered to number among his more "conservative" students, while others who started their studies while he was in Regensburg are held to be among his more "liberal" students.

However, it is true to say that his critical views on postconciliar developments tended in time to attract students more sympathetic to such views. More significant is the fact that all students, irrespective of their basic standpoint, felt at home in the colloquium.

This is because of Ratzinger's evident respect for each member, his quite remarkable ability to promote dialogue and discussion, and his tolerance of diverse viewpoints. I have never encountered anyone who could engender such a free and frank discussion as Professor Ratzinger could. And he gave his students total academic freedom in the choice and treatment of their topic.

It is therefore simply untrue to claim that it was at Regensburg "that Ratzinger began educating a generation of students who would go on to play a leading restoration role in their own national churches" (p. 92). He never set out to indoctrinate any group of students, as seems to be implied here.

The seminars and colloquium in Regensburg were places of intense debate and disagreement — and, it should be added, of wit and humor. It was also a time of intensive ecumenical activities for Ratzinger, including his pioneering lecture on the future of ecumenism at the University of Graz in 1976, his support for the various Regensburg Ecumenical Symposia, and the end-of-the-year doctoral colloquia with the Lutheran theologians Pannenberg and Joest, none of which Allen mentions.

What Professor Ratzinger taught us at Regensburg, primarily by his example, was to search for the truth with scholarly rigor, to be objective and respectful in debate, to risk unpopularity, and to give reasons for one's convictions.

I even heard the reproach that he had failed to form his own distinct "school," so diverse were his students and so open was the atmosphere he cultivated. In this, he has not changed with the years, as evidenced by the yearly meeting with his former students.

This characteristic of openness and dialogue is perhaps the key to understanding Ratzinger then as now: it is expressive of his concern for truth, which, he is convinced, will always prevail in the end (cf. p. 286), and explains both the primacy of conscience and the complementary role of the Church in his writings.

This in turn involves the greatest possible objectivity, the continual (personal and collective) search for what is in fact true, and so, openness to the opinions of others, and

the courage to speak the truth in love (veritas in caritate!).

As a result, Ratzinger manages to preserve a certain distance from all the controversies that embroil him and his office.

Contrary to what is claimed in this book he is ready to listen, is in fact a consummate listener, who once said that "All errors contain truths" (A Turning Point for Europe?, P. 108).

Consistent with this thinking is the statement in the Instruction on the 'cclesial Vocation of the Theologian'that a judgment of the Church on theological writings "does not concern the person of the theologian but the intellectual positions which he has publicly espoused".

For this reason

it is strange for Allen to claim that when "Ratzinger denounces a theologian, he also implicitly rejects his theology" (p. 242).

On the contrary, he, as Prefect, disciplines theologians because of their theology, not the other way around, and can only do so if they are recalcitrant in their refusal to accept the authoritative judgment of the Church, unpleasant though that may be. For Allen to underline the personal charm of Charles Curran, whom "virtually no one who knows him could construe as an enemy of the faith" (p. 258) is to miss the point completely.

Equally misleading is the claim by Curran (and others) that the methods of the congregation are "a violation of the most basic notions of due process" (p. 271). Such a comparison is invidious.

The process used in determining the objective orthodoxy of a theologian must of its nature be different from the process used in a court of law, which judges the subjective guilt of the criminal.

Likewise, the various penalties he has imposed on theologians disciplined by the Congregation are, no doubt, very much out of tune with the temper of the times, though to compare them — as has been done — with the penalties meted out to dissidents by totalitarian regimes in the twentieth century is grotesque, and deeply offensive to the dissidents. Those penalties are of course regrettable but, sadly, unavoidable.

They do, however, underline the significance the Church accords to theology. Ratzinger is simply fulfilling his responsibility as Prefect of the Congregation with which he has been entrusted, scrupulously adhering to the approved procedures.

Theology reflects on the revelation of ultimate human truth as handed on by the Catholic Church. It is concerned with our spiritual health, and is not a value-free academic discipline. In that regard, of course, it is in the same boat as any other serious human endeavor such as, for instance, medicine or law.

If someone wishes to practice alternative medicine, he or she is free to do so, but outside the canons of traditional medicine. Mutatis mutandis, that is what is at stake in Ratzinger's disciplining of certain theologians in recent years.

In passing judgment on the "enforcer of the faith" — itself a loaded term — Allen fails to appreciate the extent to which the Cardinal Prefect has in fact made the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith conform in the letter and spirit to the reform inaugurated by Pope Paul VI.

This was symbolized most recently, when he opened the archives of the Congregation to scholarly research (not mentioned by Allen). It is also evident in the way he takes considerable pains to give the reasons for each decision taken by the Congregation.

Few of his predecessors have provided anything like the close argumentation to be found in documents such as

Donum Vitae or the two Instructions on Liberation Theology.

Though on two occasions Allen quotes from papers read by Ratzinger to meetings held between officers of his Congregation and presidents of episcopal doctrinal commissions on various continents,

he misses the real import of such meetings.

They were attempts to enter into dialogue with the Asian, African, and American Churches, to bring the center to the periphery, as it were, to listen, to promote debate.

That Ratzinger did listen was clear to us, when at the annual meeting of his Schulerkreis, he spoke informally about various events of the previous year involving his Congregation. While in Zaire, he evidently appreciated the adaptation of the Mass to African culture, including the incorporation of ritual dance in that liturgy. He was impressed with the caliber of the Asian theologians he experienced at first hand in Hong Kong.

Apart from the seminars on papal primacy,

Allen seems unaware of various other seminars organized by the Congregation under his direction to listen to and learn from experts from around the world on controversial questions, for example, in moral theology and bioethics.

Neither is there any mention of the publication by the Pontifical Biblical Commission (under his direction) of the important document on biblical interpretation.

In addition, Cardinal Ratzinger has continued to lecture and publish in his own name as a theologian, inviting criticism.

The bibliography of his publications (including secondary literature) up to 1997 covers some 101 pages. And he continues to publish. Last year alone, for example, saw the publication of two major books, one an extended interview with a German journalist.

That he listens and responds to serious objections is illustrated by his readiness to enter into public debate, as in his extensive interview (covering two full pages) with the

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (22 September 2000) on hostile reactions to

Dominus Iesus.

Finally,

far from trying to centralize power in Rome, he has been heard to complain that, because the local bishops fail to act (or feel powerless to act when faced with a theologian who has built up his own international network), his Congregation is often reluctantly drawn into the controversy.

Allen's account of the case of Fr. Tissa Balasuriya would have been more credible, if Allen had taken the trouble to investigate the way this particular case ended up in Rome.

Allen describes a book quoted by Ratzinger (in a discussion of the pluralist theology of religions) as having a reputation for being "tendentious and error-prone, down to small details such as citing the wrong page" (p. 240,

again no source is given for this serious accusation). This is really the kettle calling the pot black.

As I have briefly described,

Allen's book is error-prone, down to small details of German spelling. It is certainly tendentious, illustrated not only by its subtitle but above all by the uncritical way he quotes accusations made by hostile witnesses, such as Hans Kung, without ever questioning their objectivity or veracity. And, apart from those gaps already mentioned, there are other serious lacunae. [The same defects are evident in his articles! But one must say that I cannot think of a single MSM Vaticanista writing about Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI who does not generally fall into the same uncritical marshalling of hostile opinion - which they don't even try to challenge at the time the false or fallacious statements are made to them!]

There is, for example,

no appreciation of Ratzinger's writings in areas such as spirituality, politics, and ethics. Many of his sermons, meditations, and retreat talks have been published, even in English, but his rich spirituality does not merit Allen's attention.

Neither is there any treatment of his substantial body of writings on politics and ethics. International recognition of his unique contribution to the field of politics and ethics came when he was appointed a "membre associe etranger" at the Academie des Sciences Morales et Politiques of the Institut de France" on 7 November 1992 in Paris, taking the seat vacated by the death of the Soviet dissident [and nuclear physicist] Andrei Sakharov.

One searches in vain for any reference to this significant fact in Allen's book.

Allen is neither a theologian nor a historian. And yet, despite its drawbacks, his book gives the reader who otherwise might not even glance at any of Cardinal Ratzinger's writings a little taste of their richness.

He conveys something of the importance of this largely underestimated theologian holding one of the central offices in the Church at this tempestuous yet exhilarating time in history. But

the price to be paid is a rather black and white approach to a man who is far more subtle, charming, and courageous than the man portrayed here.

The book is unable to convey the richness and diversity of Ratzinger's theology, which is not "derivative," as some anonymous theologian quoted by Allen claims, but highly original and seminal, covering a vast range of subjects with refreshing clarity, insight, and, yes, optimism.

Hopefully, its publication may prompt others to study his original writings, to judge for themselves — and so to enter into dialogue with one of the truly great contemporary thinkers.

Reverend Vincent Twomey, S.V.D., was ordained in 1970. He completed his doctorate at the University of Regensburg, Germany (1971-78) under the supervision of the then Professor Joseph Ratzinger. He taught theology first at the Regional Seminary of Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands then at the SVD Faculty at Modling, Austria, and is at present Lecturer on the Faculty of Theology, Pontifical University, Maynooth, Ireland.

When Allen rewrote his Cardinal Ratzinger 'biography' into The Rise of Benedict XVI: The Inside Story of How the Pope Was Elected and Where He Will Take the Catholic Church in 2005, he wrote that this time, he tried "to be fair to all sides and viewpoints", acknowledging that the first book was 'unbalanced', since it was written "before I arrived in Rome and before I really knew a lot about the universal church". The first book, he said, "gives prominent voice to criticisms of Ratzinger; it does not give equally prominent voice to how he himself would see some of these issues".

It takes a lot of chutzpah to write a biography of a man as accomplished and multifaceted as Cardinal Ratzinger is - and as consequential as Allen made him out to be (though he clearly over-reached) - and choose to write only about those aspects that would support a thesis that the writer is setting out to 'prove' with the book. And not even seek to interview the subject even once!

Why then would Allen have chosen such an ambitious project, knowing full well the effort was above and beyond him at the time he undertook it - and before coming to Rome even! I surmise that he very shrewdly planned to use it as his calling card to instant recognition, as it were, as he set about to make the contacts that he was able to establish in and around the Vatican. The prospective contacts would have thought, "He must be somebody if he wrote the first English biography of Cardinal Ratzinger! It will pay to cultivate him."

It was an especially effective ploy because in the book, he apparently marshalled together all the negative attitudes and hostility against Cardinal Ratzinger by people in the Vatican hierarchy and in the world of Catholic reporting in Italy, attitudes that had begun to coalesce after the publication of The Ratzinger Report in 1994. Hostility from people in the Vatican who did not appreciate the cardinal's candor about the crisis of faith in the Church, and from the liberal media who did not appreciate his open criticism of the progressivist mis-interpretation of Vatican II.

Fr. Twomey was perhaps too charitable to point out a most glaring error in Allen's account of the Pope's childhood, in which he uses an encyclopedia description of Aschau/Chiemgau to describe one of Joseph Ratzinger's childhood places (where he received his first Communion, among others), instead of the correct Aschau am Inn, a modest place 70 kms away from the very touristic Alpine foothill Aschau/Chiemsgau. To make such an elementary mistake is more than embarrassing. It is irresponsible. Thus, caveat emptor. As authoritative as Allen always sounds - and as infallible as much of the Anglophone world appears to consider him - he is only human. Still, he is an excellent reporter, as long as he fact-checks his own stories before posting, but has become, in the Benedict XVI years, a more and more questionable because tendentious analyst of Church affairs, especially of the Papacy.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 23/03/2013 14:10]