| | | OFFLINE | | Post: 26.156

Post: 8.648 | Registrato il: 28/08/2005

Registrato il: 20/01/2009 | Administratore | Utente Master | |

|

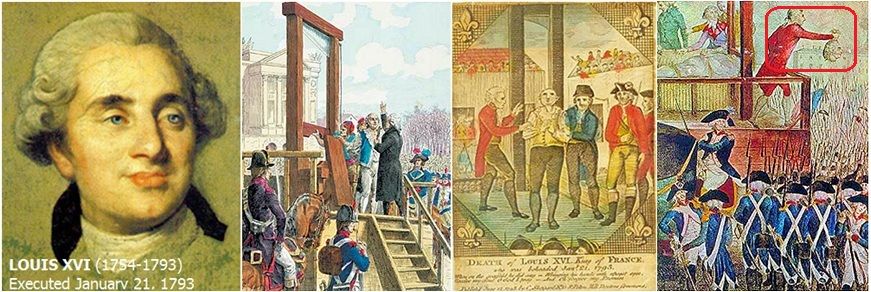

It's three days too late, but I thought I would share this unexpected serendipity on the 220th anniversary last January 21 of the execution of France's King Louis XVI. Normally, it's a subject I would not post on this thread, but this time, I will, because of the larger interpretation given to it by Albert Camus (1913-1960) from his book L'Homme Revolte, better known in English as 'The Rebel', which, to my shame, I have never read (It's a book-length essay in which he traces the development of rebellion and revolution throughout history, with the ultimate aim of denouncing Communism, which he opposed, along with all other totalitarianisms and nihilism - and in this, he differed diametrically from the other major French intellectuals of his and succeeding generations)...

It's three days too late, but I thought I would share this unexpected serendipity on the 220th anniversary last January 21 of the execution of France's King Louis XVI. Normally, it's a subject I would not post on this thread, but this time, I will, because of the larger interpretation given to it by Albert Camus (1913-1960) from his book L'Homme Revolte, better known in English as 'The Rebel', which, to my shame, I have never read (It's a book-length essay in which he traces the development of rebellion and revolution throughout history, with the ultimate aim of denouncing Communism, which he opposed, along with all other totalitarianisms and nihilism - and in this, he differed diametrically from the other major French intellectuals of his and succeeding generations)...

But his commentary on the death of Louis XVI (which I am posting here in my translation, since I can't find the official English translation online) is not to be seen as a defense of Christianity, although he is correct about the French Revolution's attempt to extirpate Christianity from French society, but as a protest against the excesses that can result from mass revolutionary politics. Indeed, probably because he was a fan of St. Augustine and his writings, he promoted the idea that the absence of religious belief can simultaneously be accompanied by a longing for 'salvation and meaning'.

The death of Louis XVI

by Albert Camus

Excerpt from L'Homme Revolte

On January 21, 1793, the murder of the King-Priest consummated what has been significantly called the Passion of Louis XVI. It is certainly a repugnant scandal to have presented the public assassination of a weak but goodhearted man as a great moment in our history.

The scaffold was not a peak – not at all. But by the expectations it raised and its actual consequences, the condemnation of the king was a watershed in our contemporary history. It symbolizes the secularization (desacralization) of this history and the disincarnation of the Christian God.

Up to that time, God had intervened in [European] history through the kings. But now his representative in history had been murdered – there no longer was a king. There only remained a semblance of God who had been relegated to the heaven of his principles.

The revolutionaries could cite the Gospels all they wanted. But what they did was to deal Christianity a terrible blow from which it has not yet recovered. Indeed, it truly seems that the execution of the King – followed, we know, by scenes of hysteria, suicides and madness – was carried out in the full awareness of those who were responsible for it.

Louis XVI may have had doubts, sometimes, about his divine right, but he systematically rejected any legislative proposal that threatened his faith.

But from the time he suspected or knew what his fate would be, he seemed to identify himself – and his language showed it - with his divine mission. It could well be said that the attempt against his person was aimed at Christ the King, the incarnation of God, and not against the craven flesh of a mere man.

The book at his bedside in the Temple prison was The Imitation of Jesus Christ. The serenity and the perfection which this man of rather average sensibilities brought to his final moments, the remarks that showed indifference to everything in the external world, and finally, his momentary weakening as he faced the scaffold alone – in the face of a terrible drumroll that drowned out his voice from being heard by the people he hoped to reach – all this allow us to think that it was not Citizen Louis Capet who was about to die, but Louis who had been king by divine right, and with him, in a way, temporal Christianity.

To better affirm this sacred bond, his confessor was there to hold him up during his final moments, by reminding him that he was suffering like the God of Sorrows. Upon which he recovered, and used the language of his God. “I will drink the cup to the dregs,”, he said.

And trembling, he delivered himself into the ignoble hands of his executioner.

Well, Monsieur Camus, wherever you are, you must see that the Western world - not just the Communists now -is more than ever committed to killing the very idea of God, though, the only emblematic figure they have today as God's surrogate is, in fact, his Vicar on earth.

Just for historical background:

The Execution of Louis XVI, 1793

Louis XVI, king of France, arrived in the wrong historical place at the wrong time and soon found himself overwhelmed by events beyond his control. Ascending the throne in 1774, Louis inherited a realm driven nearly bankrupt through the opulence of his predecessors Louis XIV and XV.

After donning the crown, things only got worse. The economy spiraled downward (unemployment in Paris in 1788 is estimated at 50%), crops failed, the price of bread and other food soared. The people were not happy. To top it off, Louis had the misfortune to marry a foreigner, the Austrian Marie Antoinette. The anger of the French people, fueled by xenophobia, targeted Marie as a prime source of their problems.

In 1788, Louis was forced to reinstate France's National Assembly (the Estates-General) which quickly curtailed the king's powers. In July of the following year, the mobs of Paris stormed the hated prison at the Bastille.

Feeling that power was shifting to their side, the mob forced the imprisonment of Louis and his family. Louis attempted escape in 1791 but was captured and returned to Paris. In 1792, the newly elected National Convention declared France a republic and brought Louis to trial for crimes against the people.

On January 20, 1793, the National Convention condemned Louis XVI to death, his execution scheduled for the next day. Louis spent that evening saying goodbye to his wife and children. The following day dawned cold and wet. Louis arose at five. At eight o'clock a guard of 1,200 horsemen arrived to escort the former king on a two-hour carriage ride to his place of execution.

Accompanying Louis, at his invitation, was a priest, Henry Essex Edgeworth, an Englishman living in France. Edgeworth recorded the event and we join his narrative as he and the fated King enter the carriage to begin their journey:

The King, finding himself seated in the carriage, where he could neither speak to me nor be spoken to without witness, kept a profound silence. I presented him with my breviary, the only book I had with me, and he seemed to accept it with pleasure: he appeared anxious that I should point out to him the psalms that were most suited to his situation, and he recited them attentively with me. The gendarmes, without speaking, seemed astonished and confounded at the tranquil piety of their monarch, to whom they doubtless never had before approached so near.

The procession lasted almost two hours; the streets were lined with citizens, all armed, some with pikes and some with guns, and the carriage was surrounded by a body of troops, formed of the most desperate people of Paris. As another precaution, they had placed before the horses a number of drums, intended to drown any noise or murmur in favour of the King; but how could they be heard? Nobody appeared either at the doors or windows, and in the street nothing was to be seen, but armed citizens - citizens, all rushing towards the commission of a crime, which perhaps they detested in their hearts.

The carriage proceeded thus in silence to the Place de Louis XV, and stopped in the middle of a large space that had been left round the scaffold: this space was surrounded with cannon, and beyond, an armed multitude extended as far as the eye could reach. As soon as the King perceived that the carriage stopped, he turned and whispered to me, 'We have arrived, if I am not mistaken”. My silence answered that we were.

One of the guards came to open the carriage door, and the gendarmes would have jumped out, but the King stopped them, and leaning his arm on my knee, 'Gentlemen,' said he, with the tone of majesty, 'I recommend to you this good man; take care that after my death no insult be offered to him - I charge you to prevent it.'…

As soon as the King had left the carriage, three guards surrounded him, and would have taken off his clothes, but he repulsed them with haughtiness- he undressed himself, untied his neckcloth, opened his shirt, and arranged it himself. The guards, whom the determined countenance of the King had for a moment disconcerted, seemed to recover their audacity.

They surrounded him again, and would have seized his hands. 'What are you attempting?' said the King, drawing back his hands. 'To bind you,' answered the wretches. 'To bind me,' said the King, with an indignant air. 'No! I shall never consent to that: do what you have been ordered, but you shall never bind me. . .'

The path leading to the scaffold was extremely rough and difficult to pass; the King was obliged to lean on my arm, and from the slowness with which he proceeded, I feared for a moment that his courage might fail; but what was my astonishment, when arrived at the last step, I felt that he suddenly let go my arm, and I saw him cross with a firm foot the breadth of the whole scaffold..

In a voice so loud, that it must have been heard it the Pont Tournant, I heard him pronounce distinctly these memorable words: 'I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I Pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France.'

He was proceeding, when a man on horseback, in the national uniform, and with a ferocious cry, ordered the drums to beat. Many voices were at the same time heard encouraging the executioners. They seemed reanimated themselves, in seizing with violence the most virtuous of Kings.

They dragged him under the blade of the guillotine, which with one stroke severed his head from his body. All this passed in a moment. The youngest of the guards, who seemed about eighteen, immediately seized the head, and showed it to the people as he walked round the scaffold; he accompanied this monstrous ceremony with the most atrocious and indecent gestures.

At first an awful silence prevailed; at length some cries of 'Vive la Republique!' were heard. By degrees the voices multiplied and in less than ten minutes this cry, a thousand times repeated became the universal shout of the multitude, and every hat was in the air.,,

References:

Cronin, Vincent, Louis and Antoinette (1975); Edgeworth, Henry in Thompson, J.M., English Witnesses of the French Revolution (1938, first published in 1812)

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 25/01/2013 00:22] |