I started out with high hopes about this article, only to find that the writer took the easy way out and strung together whole paragraphs almost taken at random from Benedict XVI's first two encyclicals. The article does have the virtue of urging the reader to go read the encyclicals themselves all over... The 'sampling' from Benedict XVI's marvelous resume of the history of ideas in the modern era from Spe salvi is almost criminal, but the fragments are still compelling...

The idea of progress in

I started out with high hopes about this article, only to find that the writer took the easy way out and strung together whole paragraphs almost taken at random from Benedict XVI's first two encyclicals. The article does have the virtue of urging the reader to go read the encyclicals themselves all over... The 'sampling' from Benedict XVI's marvelous resume of the history of ideas in the modern era from Spe salvi is almost criminal, but the fragments are still compelling...

The idea of progress in

the Magisterium of Benedict XVI

by Rodolfo Papa

The writer is a professor of the History of Aesthetic Theories at the Pontifical Urban University.

The writer is a professor of the History of Aesthetic Theories at the Pontifical Urban University.

ROME, Oct. 15 (Translated from the Italian service of ZENIT.org) - The 'hermeneutic of continuity' affirmed by Benedict XVI regarding the interpretation of the Second Vatican Council can be seen as a category that allows us to read history in a deeper and more effective way, evading the opposing traps of progressivism and regressivism.

As Cardinal Kurt Koch wrote in his recent book, "Pope Benedict XVI absolutely has no intention of turning back from Vatican II, but to proceed in depth, just like the mustard seed, which can only grow in the depths of the soil". [1]

Within this hermeneutic horizon, we can understand the analysis of 'progress' that Benedict XVI has carried out in his encyclicals.

In

Deus caritas est, Benedict XVI shows the cultural roots of the 'philosophy of progress' and the inhuman aspects inherent in it. [2] In particular, he sees in Marxism a typical example of progressivism which is realy aimed at "blocking every tendency towards a better world".

Christian charitable activity must be independent of parties and ideologies. It is not a means of changing the world ideologically, and it is not at the service of worldly stratagems, but it is a way of making present here and now the love which man always needs.

The modern age, particularly from the nineteenth century on, has been dominated by various versions of a philosophy of progress whose most radical form is Marxism.

Part of Marxist strategy is the theory of impoverishment: in a situation of unjust power, it is claimed, anyone who engages in charitable initiatives is actually serving that unjust system, making it appear at least to some extent tolerable. This in turn slows down a potential revolution and thus blocks the struggle for a better world.

Seen in this way, charity is rejected and attacked as a means of preserving the status quo. What we have here, though, is really an inhuman philosophy. People of the present are sacrificed to the moloch of the future — a future whose effective realization is at best doubtful. One does not make the world more human by refusing to act humanely here and now.

We contribute to a better world only by personally doing good now, with full commitment and wherever we have the opportunity, independently of partisan strategies and programmes. The Christian's programme — the programme of the Good Samaritan, the programme of Jesus — is “a heart which sees”. This heart sees where love is needed and acts accordingly. [4]

In

Spe Salvi, the myth of progress is analyzed in its cultural roots and criticized for its wrong premises. Above all, Benedict xVI esposes its subjectivist insufficiency - the myth of progress means that man thinks he is the author of Paradise.

Now, this “redemption”, the restoration of the lost “Paradise” is no longer expected from faith, but from the newly discovered link between science and praxis. It is not that faith is simply denied; rather it is displaced onto another level — that of purely private and other-worldly affairs — and at the same time it becomes somehow irrelevant for the world.

This programmatic vision has determined the trajectory of modern times and it also shapes the present-day crisis of faith which is essentially a crisis of Christian hope. Thus hope too, in Bacon, acquires a new form. Now it is called 'faith in progress'.

For Bacon, it is clear that the recent spate of discoveries and inventions is just the beginning; through the interplay of science and praxis, totally new discoveries will follow, a totally new world will emerge, the kingdom of man.

He even put forward a vision of foreseeable inventions—including the aeroplane and the submarine. As the ideology of progress developed further, joy at visible advances in human potential remained a continuing confirmation of faith in progress as such. [6]

Thus, the utopia of progress consists in the secularization of hope. The center of this idea of progress is the exaltaiton of scientific reason and of social and political freedom.

At the same time, two categories become increasingly central to the idea of progress: reason and freedom. Progress is primarily associated with the growing dominion of reason, and this reason is obviously considered to be a force of good and a force for good.

Progress is the overcoming of all forms of dependency—it is progress towards perfect freedom. Likewise freedom is seen purely as a promise, in which man becomes more and more fully himself.

In the 19th century, hope was seen in terms of 'faith in progress', but at the same time, the limits of progress itself were being manifested, especially with the explosion of the social question of laborers:

The nineteenth century held fast to its faith in progress as the new form of human hope, and it continued to consider reason and freedom as the guiding stars to be followed along the path of hope.

Nevertheless, the increasingly rapid advance of technical development and the industrialization connected with it soon gave rise to an entirely new social situation: there emerged a class of industrial workers and the so-called “industrial proletariat”, whose dreadful living conditions Friedrich Engels described alarmingly in 1845.

For his readers, the conclusion is clear: this cannot continue; a change is necessary. Yet the change would shake up and overturn the entire structure of bourgeois society. After the bourgeois revolution of 1789, the time had come for a new, proletarian revolution: progress could not simply continue in small, linear steps. A revolutionary leap was needed.

Karl Marx took up the rallying call, and applied his incisive language and intellect to the task of launching this major new and, as he thought, definitive step in history towards salvation — towards what Kant had described as the “Kingdom of God”. Once the truth of the hereafter had been rejected, it would then be a question of establishing the truth of the here and now.

The critique of Heaven is transformed into the critique of earth, the critique of theology into the critique of politics. Progress towards the better, towards the definitively good world, no longer comes simply from science but from politics — from a scientifically conceived politics that recognizes the structure of history and society and thus points out the road towards revolution, towards all-encompassing change.

With great precision, albeit with a certain onesided bias, Marx described the situation of his time, and with great analytical skill he spelled out the paths leading to revolution—and not only theoretically: by means of the Communist Party that came into being from the Communist Manifesto of 1848, he set it in motion.

His promise, owing to the acuteness of his analysis and his clear indication of the means for radical change, was and still remains an endless source of fascination. Real revolution followed, in the most radical way in Russia. [7]

Overcoming the ambiguities of progress means going through a critque of progress itself. The Pontiff refers to Theodor Adorno:

First we must ask ourselves: what does “progress” really mean; what does it promise and what does it not promise? In the nineteenth century, faith in progress was already subject to critique.

In the twentieth century, Theodor W. Adorno formulated the problem of faith in progress quite drastically: he said that progress, seen accurately, is progress from the sling to the atom bomb. Now this is certainly an aspect of progress that must not be concealed.

To put it another way: the ambiguity of progress becomes evident. Without doubt, it offers new possibilities for good, but it also opens up appalling possibilities for evil—possibilities that formerly did not exist.

We have all witnessed the way in which progress, in the wrong hands, can become and has indeed become a terrifying progress in evil. If technical progress is not matched by corresponding progress in man's ethical formation, in man's inner growth (cf. Eph 3:16; 2 Cor 4:16), then it is not progress at all, but a threat for man and for the world. [8]

The only true progress is that which forms man in the mloral sense.

First of all, we must acknowledge that incremental progress is possible only in the material sphere. Here, amid our growing knowledge of the structure of matter and in the light of ever more advanced inventions, we clearly see continuous progress towards an ever greater mastery of nature.

Yet in the field of ethical awareness and moral decision-making, there is no similar possibility of accumulation for the simple reason that man's freedom is always new and he must always make his decisions anew. These decisions can never simply be made for us in advance by others — if that were the case, we would no longer be free.

Freedom presupposes that in fundamental decisions, every person and every generation is a new beginning. Naturally, new generations can build on the knowledge and experience of those who went before, and they can draw upon the moral treasury of the whole of humanity.

But they can also reject it, because it can never be self-evident in the same way as material inventions. The moral treasury of humanity is not readily at hand like tools that we use; it is present as an appeal to freedom and a possibility for it. [0]

The solution to the ambiguities of human progress is in the theological virtue of Hope, which is not the expectation of a better future but certainty of salvation: “Spe salvi facti sumus” (In hope we are saved) (Rm 8,24).

Benedict XVI's recurrent reflections on the parable of the mustard seed (Mk 4,30-42) can further enlighten us. As Cardinal Koch writes,

"The mustard seed is not just a metaphor for Christian hope but it is also evidence that the great can grow from the small even without revolutionary distortions, nor even because we men have taken on the direction of our affairs, but because such development takes place slowly and gradually, following its own dynamic. In the face of this, the Christian attitude can only be that of love and patience, which is the long breath of love" [10].

NOTES

[1] K. Koch, Il mistero del granello di senape. Fondamenti del pensiero teologico di Benedetto XVI, trad.it., Lindau, Torino 2012.

[2] Per quanto segue, cfr. R. Papa, Discorsi sull’arte sacra, Cantagalli, Siena 2012, cap. III.

[3] Benedetto XVI, Deus caritas est, 25 dicembre 2005, n. 17 – corsivo aggiunto.

[4] Ibid., n. 31 b – corsivo aggiunto.

[5] Id., Spe salvi, 30 novembre 2007, n. 17 – corsivo aggiunto.

[6] Ibid., n. 18 – corsivo aggiunto.

[7] Ibid., n. 20 – corsivo aggiunto.

[8] Ibid., n. 22 – corsivo aggiunto.

[9] Ibid., n. 24.

[10] K. Koch, Il mistero del granello di senape, p. 8.

Not my day! This item had a very catchy title, it was in the Economics and Finance section of Il Sussidiario which is a serious and respectable online journal, and it was quoting a leading Italian economist.... Alas, what the writer quotes turns out to be nothing but a generic hodge-podge that is surely an injustice both to the economist bimself and to the Social Doctrine of the Church... But I suckered myself into translating it, so I'm keeping it in...

What if the Nobel Prize for economy is to be

Not my day! This item had a very catchy title, it was in the Economics and Finance section of Il Sussidiario which is a serious and respectable online journal, and it was quoting a leading Italian economist.... Alas, what the writer quotes turns out to be nothing but a generic hodge-podge that is surely an injustice both to the economist bimself and to the Social Doctrine of the Church... But I suckered myself into translating it, so I'm keeping it in...

What if the Nobel Prize for economy is to be

found in the Social Doctrine of the Church

by Gianfranco Fabi

Translated from

October 21, 2012

Luigi Pasinetti says, "The Social Doctrine of the Church constitutes the most complete and relevant response to the difficulties of economic theories in the face of the contemporary crisis".

His name is certainly not known to the public, he does not write for the newspapers, he does not appear on TV. And yet, he is one of the leading contemporary economists, emeritus professor at the Catholic University, who also taught in Cambridge University for many years, and the author of an incredible number of books and essays.

The Catholic University has now published a book with two interventions of Pasinetti (in 1992 and 2010) on "The Social Doctrine of the Church and economic theory" (Vita e Pensiero, 130 pp). In both he underscores with extreme frankness how the dominant economic theory is profoundly inadequate to comprehend the problems of a society as deeply dynamic as that of today.

"Traditional economists," he writes, "move within the strong restrictions of arguments that are based on the 'model of pure exchange', a theoretical model which was inadequate even to confront the problems of industrial society. That is why economists are 'quite unwise' and 'devoid of all justification' if they do not consider the advice of the Church on the moral principles that must be the basis of criteria for responsible construction of our institutions."

His more recent intervention is even more explicit. Starting off with the observation that "economic theory is going through a very critical period which truly requires a severe and radical reconsideration of its fundamentals".

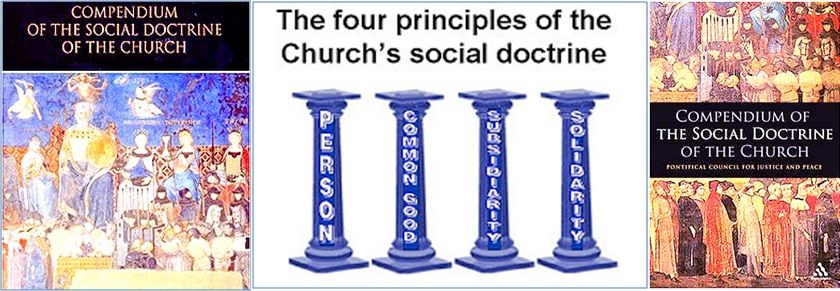

Pasinetti underscores the importance of the Social Doctrine of the Church with "its insistence on essential principles, such as the rights and dignity of the human person, knowing that in the historical epoch we are living, responsibility has gone beyond national frontiers".

His critique of dominant economic theories appears explicit and unqualified. It is as though the economy, with irresponsible certainty, has simply gone down the paths of quantitative principles, of the logic of interests, of

a posteriori justifications of decisions that must perennially be brought back to rationality.

Pasinetti thus calls for paying "more attention to those characteristics which are radically new and so marked in our society, like the dynamic taken on by technological and social events and the profound demands generated by globalization, such as the need to protect the environment at the global level and the growing relevance of the principle of the universal destination of goods".

Particularly relevant is Pasinetti's admission that he was "struck and surprised" by the statement on the dynamic of charity expressed decisively in the encyclical

Caritas in veritate that he ends his essay with an explicit but hardly usual "Grazie, Benedetto!"

The economist expresses his admiration for the constant insistence by the Church, starting with

Rerum novarum, to values that economic theories do not take into account, do not even consider, and basically, do not understand.

And yet the mainstays of the Social Doctrine of the Church - such as the principles of solidarity, subsidiarity, and the common good - could concretely help the economy and economists to emerge from the aridity they are headed for and from which it seems increasingly difficult to leave, just using old instruments and old theories.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 22/10/2012 07:30]