See preceding page for earlier posts today, 12/7/10.

See preceding page for earlier posts today, 12/7/10.

In Genoa, Cardinal Bagnasco presents

In Genoa, Cardinal Bagnasco presents

Ratzinger's 'The Theology of Liturgy'

from his Complete Works

GENOA, Dec. 7 (Translated from SIR) - "To concern oneself with liturgy does not mean forgetting the difficulties encountered by the Christian faith today in the face of contemporary culture. On the contrary, it is an elevated testimonial to what constitutes the heart of the Christian faith".

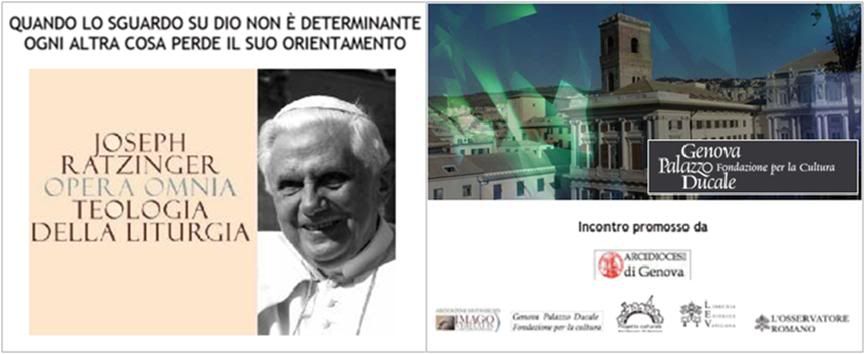

Thus did Cardinal Angelo Bagnasco, Archbishop of Genoa and president of the Italian bishops' conference, present today Volume XI of Joseph Ratzinger's

Complete Works, entitled

The Theology of Liturgy, in its Italian edition, at the Palazzo Ducale, which now serves as Genoa's main cultural center.

The epigraph on the poster says: "When God is not the decisive factor, then everything else loses orientation".

The epigraph on the poster says: "When God is not the decisive factor, then everything else loses orientation".

The other presenters were Prof. Sandra Isetta, of the University of Genoa, and Prof. Lucetta Scaraffia, of the La Sapienza University in Rome. The moderator was Giovanni Maria Vian, editor of

L'Osservatore Romano.

[NB: At the express desire of Benedict XVI, the Regensburg-based Institut Papst Benedikt XVI which is publishing the

Complete Works in 16 volumes through Herder, the first volume released was the one that collects his writing on liturgy, including the two books he had written about it earlier. Five volumes of the

Complete Works have already been published in German since the fall of 2008. This is the first volume of the Italian edition, published by the Vatican publishing house.]

Liturgy, said Cardinal Bagnasco, manifests to the world the primacy of God, because the Church "when it celebrates a liturgy, also manifests itself as a reality that cannot be reduced to its earthly and structural aspects".

"Liturgy makes it clear," he said, "that the pulsing heart of the Christian world is found beyond the confines of earth. More than that, liturgy demonstrates how everything else is subordinate to this 'Other'."

Also, "man does not create the rite - he receives it from a tradition that embodies the faith of centuries", and therefore, "in the celebration of liturgy, so much more is taking place than anything that we can think of to invent from time to time".

It is in this context, he pointed out, that explains "Benedict XVI's concern to protect the liturgy from undue manipulations, which could be induced by an incorrect application of Vatican II's decree regarding the 'active participation' of the faithful".

That is why "appropriate celebration of liturgy, which comes from obedience to liturgical norms, is not a nostalgic residue of ritualism but a wise use of the various means employed in liturgy to express our encounter with God... Beyond expressing the absolute primacy of God, the liturgy also manifests that he is God-with-us"...

The cardinal says that in

The Theology of Liturgy, theologian Ratzinger likened liturgy to physical training because "to celebrate the liturgy is to allow oneself to be shaped by the completely Other, God".

Therefore, "participation in liturgy must be active, but at the same time, passive or initiatory. Attention to the initiatory aspect of liturgy does not mean reforms which the liturgy undergoes from time to time but the internal reform that the liturgy promotes through its ritual and leads the faithful to the heart of the mystery that is celebrated".

He concluded:

"We are grateful to the theologian Joseph Ratzinger and to Pope Benedict XVI for the work of profound renewal carried forward in the Church so that she may be ever more faithful to her Lord and to her living Tradition.

"With disarming clarity, he brings to light, explains and examines in depth the centrality of liturgy affirmed by the Second Vatican Council which defined it as 'the source and peak' of Christian life, and of the life and mission of the Church".

The following is an extract from the presentation text of Prof. Isetta, excerpted rather unevenly in L'Osservatore Romano, especially the first part.

Christian art and

a new experience of time

by Sandra Isetta

Translated from the 12/6-12/7 issue of

In this volume, Joseph Ratzinger analyzes one of the thorniest questions in liturgy: self-determination of the form of worship. Liturgy cannot be do-it-yourself. Liturgy is 'made' by man for God and not for ourselves. And the more we make it for ourselves, for our own purposes, the less attractive it becomes.

"Humility and obedience are not servile virtues which repress men, but are the opposite of arrogance and presumptuousness which fragment any community and can lead to violence", just as conformism today limits man to the superficial.

The golden calf was a testimonial to arbitrary worship: with the idol, the Israelites did not wish to distance themselves from God - they thought it was a way to glorify the God who had led them out of Egypt.

And yet they were defecting from God, not believing in his invisible image. And their form of worship was no longer a going forward to him, but a retreat downward towards the purely human dimension. Thus liturgy becomes empty play, a betrayal of God, camouflaged by a mantle of sacrality.

But thanks to the linearity of reason and language, complicated theological concepts become accessible.

For example, the opposition between worship that is cosmically oriented, which is typical of natural religions and leads to a sort of exchange between divinities and men, and worship as revealed in history - in Judaism, in Christianity and in Islam.

Joseph Ratzinger softens this sharp opposition between the cosmic and historical orientations of worship by interpreting the story of creation, oriented to the Sabbath. It is the day on which man and all creation take part in God's resting, a freedom during which master and slave are equal - when all relationships of subordination and the effort of work itself are suspended.

The Sabbath is the sign of the Covenant that God wished to establish with man, and creation is the place of this encounter, for man to adore God.

These essentials from the Old Testament are taken up in the third part of this volume under the title 'The celebration of the Eucharist', comprising 300 pages in 11 sections.

It begins with the significance of the Christian Sunday which takes the place of the Jewish Sabbath. Exegesis and theology compenetrate in explaining the third day, the day of theophany.

In the Old Testament, the Covenant on Sinai is stipulated on the third day. In the New testament, Jesus resurrects on the third day after his death.

For the early Christians, Sunday was 'the Lord's day', the 'first' if the seven days of creation, the day when light was created. It is also the eighth day that opens up the door to eternity after the Sabbath.

christian worship, through its Biblical roots, is thus not an imitation of the cosmos but of God revealing himself. The objective of worship and the objective of creation are identical, because the historical dimension is part of the cosmic dimension.

Creation establishes a dialog of love and the Christian idea of "God is everything for everyone". An ascent, a return home to God. is impossible with one's forces alone. One needs sacrifice - which is the essence of worship - and sacrifice is the opposite of total autonomy, of not needing anybody else.

Ratzinger offers an ample discussion on the significance of art which starts with historico-archaeological references. Judaism in the time of Jesus represented images of the mystery of salvation taken from the Messianic episodes of the Old Testament.

Subsequently, whereas Judaism and Islam responded rigorously to the iconoclastic war, agreeing to limit representations only to abstractions and geometrics, Christianity continued with its figurative accounts (haggadà) of the gestures performed by God.

And it's true, as Ratzinger states, that the continuity between Synagogue and Church is preserved in the Christian art in the catacombs, which rendered and therefore celebrated events of the past through memory transformed into figures.

Events in the Old Testament are laid beside - and therefore interpreted in the light of - the New: Noah's Ark and the passage through the Red Sea are figures of Baptism; the sacrifice of Isaac and Abraham's meal with the three angels recall the sacrifice of Christ and the Eucharist.

Christian art represents 'a new experience of time', in which "past, present and future touch each other" in the 'Christological concentration of history'.

This is the very same concept of the 'liturgical present' which always carries 'eschatological hope' in it.

The early images were therefore allegorical, like the Good Shepherd who epitomizes the entire history of salvation: which is to bring home up to the very last lost lamb.

Farther on, there is a liturgical correlative in the Agnus Dei - the Shepherd is now the Lamb who carries our sins, which we recall by striking the breast.

Starting with the sixth century, with the appearance of the first mysterious images called acherotypes - namely, not produced by human hand (e.g., the Mandylion of Odessa, or the Holy Face of Mannopello)- the Christian Orient elaborated a true and proper theology of the icon, in which the icon of Christ was always the Risen One, where the facial features did not matter, but served as the vehicle for looking beyond the sensible, like the disciples at Emmaus who needed to see with other eyes in order to recognize the Lord in the same light as the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor. The Trinitarian and ontological vastness of the iconography of the Son allows as to see the image of the Father.

Ratzinger reviews the most significant stages of Christian figurative art, starting from the pedagogical purpose of Western art compared to Oriental art, from Augustine and Gregory the Great to the Romanesque.

In the West, the Gothic replaced the Pantocrator, or Lord of the universe in the fullness of the eighth day, with the Crucified One in his passion and death.

He indicates the philosophical motivations for the change from Platonism to Aristotelianism with consequences in art and liturgy which emphasize historicity over the beauty of the invisible.

He cites Matthias Grünewald and the realism of suffering, explaining the consolatory function of this art for those who were afflicted with the plague, and for popular piety in general.

He underscores the aesthetic aspect of the Renaissance, because it ‘emancipates’ man, its autonomy and beauty almost like ‘a nostalgia for the gods, for myths’, which cancel out sin and suffering on the Cross, and can even explain the reaction of the Catholic Counter Reformation. He defines the Baroque as “a very powerful hymn of joy, a Hallelujah that has become image”.

Then he comes to positivism, formulated in the name of scientific seriousness which, however, “restricted the horizon to the demonstrable, cutting off the world from transparency and man from the vision of the invisible”.

Finally, he asks about 'our world of image’ today which could perhaps mark ‘the end of the image’.

He draws again from the first representations found in the catacombs to explain the positions of liturgy – being together, seated together. In which the praying figure is always female, "because the human characteristic before God finds expression in the figure of the woman", who represents not the Church but “the soul spouse who is in adoration of the face of God'.

When the hands are spread apart, it is a gesture of non-violence, like wings preparing to fly, or like Christ’s arms on the Cross, which is also the form of the basic plan of churches.

The praying figure is usually standing – ‘the position of triumph, as well as the readiness to take off, to journey towards the future'. Kneeling reveals our ‘now’ which is our ‘meanwhile’, whereas sitting, which was introduced more recently, serves for contemplation, to facilitate listening and understanding, with the body relaxed.

The gesture of hands brought together is the expression of trust and fidelity. And bowing is both a physical and spiritual gesture, a corporeal expression of humility, ‘a gesture that the Greeks considered servile’. It is a fundamental Christian attitude, on which Augustine constructed his Christologic theology: hubris, arrogance, is opposed by humilitas, since the Lord himself had bowed down to wash the feet of the apostles, ‘kneeling at our feet, that is where we find him”.

Ratzinger follows this with a splendid definition of the 'body' in Biblical language, which refers to the entire person in which body and spirit are inseparably one thing only. “This is my Body” therefore says: This is my entire person who lives in the body, in which the body is both confinement and communion.

He cites Albert Camus on the ‘tragic condition of men in their reciprocal relationships - as if two persons are separated by a glass wall of a telephone booth: they see each other, they are very close, but the wall makes them unreachable to each other”.

Various pages dedicated to the Corpus Domini, dense with theological concepts, but also with his personal recollections of the splendor of Corpus Domini processions in his native Bavaria. To carry the Lord himself, the Creator, through cities and villages, through fields and lakes, is to say that through liturgy, men deals with ”everything that heaven and earth enclose, mankind and all creation" in the common memory.

“A sort of reaction to the forgetfulness of our relationship with time in the era of the computer, of meetings and agendas, used today even by schoolchildren who have become frighteningly carefree and forgetful. (Today), our relationship with time is to forget. We live in the moment. In fact, we want to forget because we deny old age and death. The only way to truly confront time is forgiveness and gratitude – attitudes that receive time as gift, and transform it in gratitude”.

He discusses the ‘noble simplicity’ of rites, that ‘extreme simplicity’ which corresponds to ‘the simplicity of the infinite God and refers to him’. But it must be ‘perceived with the eye and the heart’, in the great simplicity of a little village church as in the great solemnity of the beauty of a cathedral. The condition is that ‘grandiosity and sumptuousness are not autonomous, but must serve humbly to underscore

the true celebration, the birthday, as it were, of life’s assent to God.

He concludes with a reflection on Nietzsche. “Celebration brings pride, swagger, abandon… a divine Yes to oneself brought on by animal-like fullness and integralness’ – all of them conditions to which a Christian cannot honestly agree with, or celebration would be paganism par excellence.

The opposite is true: only when there is a divine legitimacy for rejoicing – only when God guarantees that my life and the world are reasons for joy – only then can there be a true celebration.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 08/12/2010 11:51]