When all of us become children

When all of us become children

by JOSEPH RATZINGER

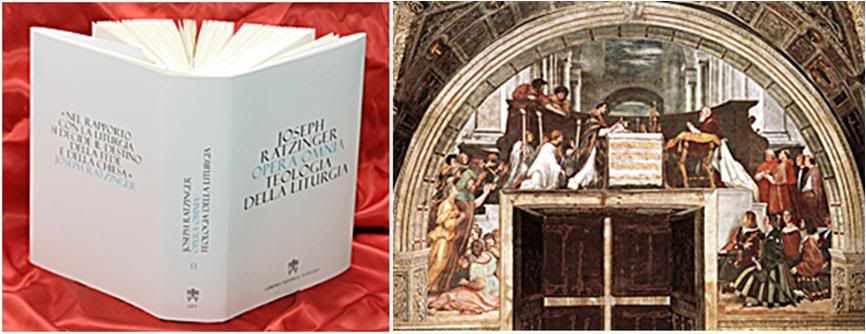

Teologia della liturgia: La fondazione sacramentale dell'esistenza Cristiana (Vatican City, LEV, 2010, 849 pp, 55 euro) is the volume that inaugurates the publication of the Italian translation by Ingrid Stampa of Joseph Ratzinger's Opera Omnia (Collected Works). The Italian edition is edited by Edmond Caruana and Pierluca Azzaro.

Teologia della liturgia: La fondazione sacramentale dell'esistenza Cristiana (Vatican City, LEV, 2010, 849 pp, 55 euro) is the volume that inaugurates the publication of the Italian translation by Ingrid Stampa of Joseph Ratzinger's Opera Omnia (Collected Works). The Italian edition is edited by Edmond Caruana and Pierluca Azzaro.

"When, after some hesitation, I decided to approve the project of publishing all my writings," Benedict XVI wrote on June 29, 2008, "it was clear to me that it should be according to the order of priority followed by the (Second Vatican) Council. and therefore, it should start with my writings about liturgy. The liturgy of the Church has been, since my childhood, the central reality of my life and, in the theological school of masters like Schamus. Soehngen, Pascher and Guardini, it had also become the center of my theological commitment".

We publish here the start of the first Chapter of Vol. I dedicated to the "nature of liturgy', along with the Preface written for the Italian edition by Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone.

Liturgy - what is it really? What takes place in it? What kind of reality do we encounter?

In the 1920s, it was proposed to consider liturgy as 'play' - the term of comparison was first of all, the fact that liturgy, like play, has its own rules, creates its own world, which is valid once you enter and which naturally recedes when play is over.

Another term of comparison was the fact that a game has sense, but at the same time, it has no specific purpose, and therefore it is somewhat therapeutic, even liberating, because it makes us leave the world of daily routine withits constraints and introduces us to a dimension without purpose, thus liberating us for a certain time from all the weight of our world of work.

Play would be, so to speak, a different world, an oasis of freedom, in which for some time, we can let our being 'flow' freely - we need such moments of escape from the tyranny of daily routine in order to be able to bear its weight.

There is something true in all this, but such an observation does not suffice. Indeed, what kind of play we dedicate ourselves to would then be basically secondary. Everything above can be applied to any game, in which the intrinsically necessary seriousness of observing its rules soon becomes an effort in itself and also leads to elaborating new specific purposes.

If we think of the present world of sport, the world chess championship or any other game, it is evident in all cases that play has the completely different dimension of an alternative world or a non-world, but soon becomes a specific world with its own laws if one is not simply to lose onself in simple empty leisure.

There is yet another aspect of the theory of play that merits mention and which brings us much closer to the particular nature of liturgy: child's play appears largely as a kind of anticipating life, as an exercise for entering into later life, without the actual effort and its seriousness.

Thus, liturgy can lead us to think that before getting to the true and proper life that we wish to reach, we basically remain as children, or at least, we should remain children. Then, liturgy becomes a completely different kind of anticipation, of preliminary exercise: a prelude to a future life, to eternal life which, as St. Augustine says, unlike the present life, is no longer characterized by needs and necessity, but entirely of the freedom to give and of giving itself.

Then, liturgy would be an awakening of the true child in our most intimate core, an awakening of our interior openness to the great things that await us which will not be fulfilled even in our adult life.

It would be a structured form of hope which already anticipates that future life, the real one, which trains us for authentic life: that of freedom, of God's immediacy, and of direct reciprocal openness.

It would also imprint on our apparently real life, that of the day-to-day, the anticipatory signs of the freedom that shatters constraints and brings to earth a reflection of heaven.

Such an interpretation of the theory of play differentiates liturgy essentially from common play, because it retains the 'nostalgia' for true 'play'- for the total 'otherness' of a world in which order and freedom blend into each other.

In comparison to the superficial and humanly void character of usual play, such an interpretation causes to emerge that special quality and otherness of the 'play' of Wisdom, which the Bible speaks about, and which therefore can be related to liturgy.

But an essential content is still lacking from this sketch, since the idea of future life has so far appeared only as a vague postulate, and looking at God, without which any 'future life' could only be a desert, still remains indeterminate. Thus I wish to propose a new approach, this time starting with the concreteness of Biblical texts.

In the narration of the events that preceded Israel's coming out of Egypt, just as in the actual event itself, two different purposes emerge for the exodus.

One, known to all, is to reach the Promised Land, where Israel could finally live on its own territory, with secure borders, as a people with its own freedom and independence.

Alongside that end, however, an indication of a different end appears repeatedly. The original command by God to the Pharaoh was "Let my people go, so they can serve me in the desert!" (Ex 7,16). This command "Let my people go so they can serve me in the desert" is repeated with small variations four times, in each of the encounters between the Pharaoh and Moses/Aaron (Ex 7,26; 9,1; 9,13; 10,3).

During their negotiations with the Pharaoh, the objective is further concretized. For him, the conflict has to do with the Israelites' freedom of worship, which he initially concedes this way: "Go and sacrifice to your God provided you do not go far away" (Ex 8,24).

After the succession of plagues, the Pharaoh widens his offer of compromise. Now he concedes that the worship be done according to the will of the divinity, namely, in the desert, but demands that only men can do this, and that women and children, along with their animals, must remain in Egypt.

He presumed a cultual practice that was current then, according to which only men could be active protagonists in worship. But Moses could not negotiate the modality of worship with a foreigner - he could not subordinate worship to political compromises: the way to render worship is not a question that can be resolved politically.

Worship has its own norms - it can be regulated only on the basis of Revelation, starting from God. That is why he also rejected the sovereign's third offer of compromise, who now broadened it to include even the women and children. "But your flocks and herds must remain!" (Ex 10,24).

Moses objects that they should bring all their animals with them because "we ourselves shall not know which ones we must sacrifice to him until we arrive at the place itself" (Ex 10,26).

None of this is about the Promised Land: the only purpose of the Exodus appears to be adoration, which can only take place according to God's norm, and is therefore not subject to the rules of the game of political compromise.

Israel was not leaving Egypt to be a people like everyone else - it was leaving to serve God. The destination of the Exodus is the mountain of God, still unknown, and its purpose was to render service to God.

At this point, one might object that remaining obstinate about worship in the negotiations with the Pharaoh was tactical in nature. The real and, definitely, the only purpose of the Exodus was not worship but the Land, which constituted the true and proper content of the promise made to Abraham.

I do not think this does justice to the seriousness that dominates these texts. Basically, an opposition between Land and worship makes no sense: the Land is given so that it may be a place for adoration of the true God.

The simple possession of the Land, mere national autonomy, would demote Israel to the level of all other peoples. To reduce everything to this end would mean a failure to recognize the specialness of God's choice: the entire history narrated by the books of Judges and Kings, taken up again and reinterpreted in Chronicles, shows precisely this. Land in itself, taken by itself, is a still indeterminate benefit -

it would become true good, the real gift of a promise fulfilled, only if God reigns in it, not just because the land exists in some way as an autonomous State, but if it is the space for obedience, in which the will of God is done, as only in this way can human existence carry on in a just way.

Examination of the Biblical text, however, gives us an even more precise definition of the relationship between the two aims of the Exodus. It is true that Israel on the move still did not know after three days (as Moses said in his discourse with the Pharaoh) what kind of sacrifice God demanded.

Three months after their departure, however, "on its first day, the Israelites came to the desert of Sinai" (Ex 19,1). And on the third day, God came down to the mountain peak (19,16-20). And now he speaks to the people: In the holy Decalogue (20,1-17) he communicates his will, and through Moses, he establishes the Covenant (Ex 24) which is concretized in a minutely regulated form of worship.

Thus the purpose of the pilgrimage into the desert, which had been given to the Pharaoh, was fulfilled: Israel learned to venerate God in the way which he himself wishes.

Worship belongs to such veneration - liturgy in its true and proper sense. But it also requires living according to the will of God, which is an irrenunciable part of correct adoration.

"The glory of God is the living man, but the life of man is to see God", said St. Irinaeus, grasping the very nucleus of what took place at that encounter of the mountain in the desert of Sinai.

In short, the life of man itself, of the man who lives correctly, is the true adoration of God, but life becomes real only if it takes its form while one is looking at God. This is the purpose of worship: to allow such a look at God and thus to Live that liFe which becomes the glory of God.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 29/06/2010 23:25]