| | | OFFLINE | | Post: 32.827

Post: 14.909 | Registrato il: 28/08/2005

Registrato il: 20/01/2009 | Administratore | Utente Gold | |

|

I am most thankful to Sandro Magister for having been the only person, to my knowledge, who reacted to Mons. Viganò’s full-throated denunciation of Vatican II last month, which reads in parts like a direct slap at Benedict XVI, never mind that since the end of Vatican II, he had always fought to underscore proactively – as professor, theologian, archbishop, then as cardinal and Pope - that the Council texts must not be interpreted as a rupture with what the Church has always taught.

I am most thankful to Sandro Magister for having been the only person, to my knowledge, who reacted to Mons. Viganò’s full-throated denunciation of Vatican II last month, which reads in parts like a direct slap at Benedict XVI, never mind that since the end of Vatican II, he had always fought to underscore proactively – as professor, theologian, archbishop, then as cardinal and Pope - that the Council texts must not be interpreted as a rupture with what the Church has always taught.

Even if, one must admit that in 1985, 20 years after the Council closed, when John Paul II convened a special synod to ‘institutionalize’ the right interpretation and application of Vatican II, the discontinuity narrative had already taken over key sectors of the Church, as Joseph Ratzinger himself denounced so forcefully in the RATZINGER REPORT of 1984 [in Italian, RAPPORTO SULLA FEDE (Report on the faith)] that preceded the synod.

And that in 2005, another 20 years later, when, as Pope, he delivered his seminal address on the ‘hermeneutic of continuity in renewal’ – as beautifully reasoned and attention-grabbing as it was - it seemed to have been more a question of enunciating that hermeneutic in a papal document, for the record, not out of any real expectation of reversing the havoc already wrought on the Church by the ‘spirit of Vatican II’ cardinals, bishops and priests who had systematically sought to influence dioceses, parishes, seminaries and Catholic schools around the world and win them over to their progressivist hermeneutic of rupture.

The new debate over Vatican II that Mons. Viganò’s broadside has ignited has since taken a number of turns, but let us begin with Magister.

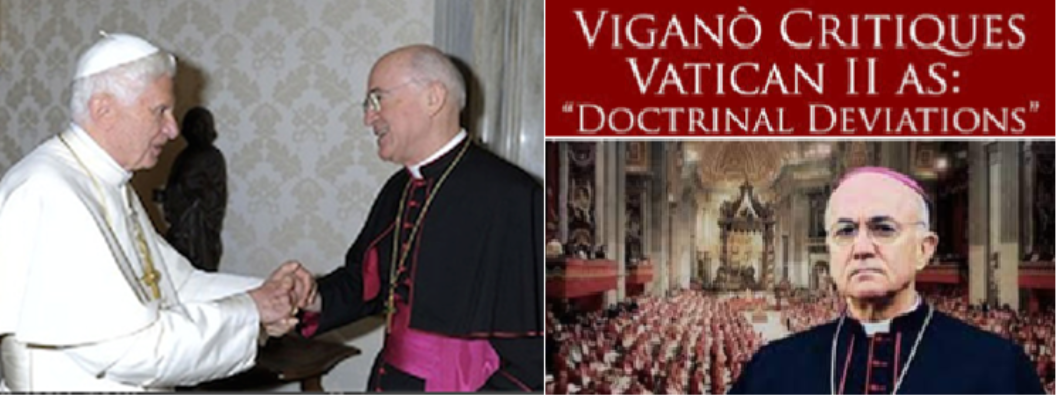

Archbishop Viganò on the brink of schism:

The unheeded lesson of Benedict XVI

June 29, 2020

Benedict XVI promoted him to apostolic nuncio in the United States in 2011. The meek theologian pope certainly could not have imagined, nine years ago, that Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò - who returned to private life in 2016 but has been anything but hidden - would today be blaming him for having “deceived” the whole Church in that he would have it be believed that the Second Vatican Council was immune to heresies and moreover should be interpreted in perfect continuity with true perennial doctrine.

Because this is just the length to which Viganò has gone in recent days, capping off a relentless barrage of denunciations of Church heresies over the last few decades, with the root of it all being the Council, most recently in an exchange with Phil Lawler, editor of CatholicCulture.org. [Posted earlier on this thread]

Attention! Not the Council interpreted badly, but the Council as such and en bloc. In his latest public statements, in fact, Viganò has rejected as too timid and vacuous even the claim of some to “correct” Vatican II here and there, in its texts which in his judgment are more blatantly heretical, such as the declaration “Dignitatis Humanae” on religious freedom.

Because what must be done once and for all - he has demanded - is "to drop it 'in toto' and forget it.” Naturally with the concomitant “expulsion from the sacred precinct” of all those Church authorities who, identified as guilty of the deception and “invited to amend,” have not changed their ways.

According to Viganò, what has distorted the Church ever since the Council is a sort of “universal religion whose first theoretician was Freemasonry.” And whose political arm is that “completely out-of-control world government” pursued by the “nameless and faceless” powers that are now bending to their own interests even the coronavirus pandemic.

Last May 8, Cardinals Gerhard Müller and Joseph Zen Zekiun also carelessly affixed their signatures to an appeal by Viganò against this looming “New World Order.” Just as to a subsequent open letter from Viganò to Donald Trump - whom he invoked as a warrior of light against the power of darkness that acts both in the “deep state” and in the “deep Church” - the president of the United States replied enthusiastically, with a tweet that went viral.

But getting back to the reckless indictment launched by Viganò against Benedict XVI for his “failed attempts to correct conciliar excesses by invoking the hermeneutic of continuity,” it is obligatory to give the accused the right to speak.

The hermeneutic of continuity - or more precisely: “the ‘hermeneutic of reform,’ of renewal in the continuity of the one subject-Church” - is in fact the keystone of the interpretation that Benedict XVI gave of Vatican Council II, in his memorable address to the Vatican curia on Christmas Eve of 2005, the first year of his pontificate.

It is a speech that is absolutely to be reread in its entirety:

http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2005/december/documents/hf_ben_xvi_spe_20051222_roman-curia.html

But here in summation is how Papa Ratzinger developed his exegesis of Vatican Council II. He began by recalling that also after the Council of Nicaea in 325 the Church was rocked by the most heated conflicts, which made St. Basil write:

“The raucous shouting of those who through disagreement rise up against one another, the incomprehensible chatter, the confused din of uninterrupted clamouring, has now filled almost the whole of the Church, falsifying through excess or failure the right doctrine of the faith...”

But why has the aftermath of Vatican II been so contentious as well? Benedict XVI's answer is that everything has depended “on its hermeneutic,” meaning on the “key to interpreting and applying it.” The conflict has arisen from the fact that “two contrary hermeneutics came face to face and quarrelled with each other’’. On the one hand there was a “hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture.” On the other, a “hermeneutic of reform, of renewal in the continuity of the one subject-Church.”

According to the first hermeneutic, "it would be necessary not to follow the texts of the Council but its spirit,” making room for “impulses toward the new” that are seen as underlying the texts, “in which, to reach unanimity, it was found necessary to keep and reconfirm many old things that are now pointless.”

But with this - the pope objected – “the nature of a Council as such is therefore basically misunderstood. In this way, it is considered as a sort of constituent that eliminates an old constitution and creates a new one.” When instead “the essential constitution of the Church comes from the Lord” and the bishops need simply be its faithful and wise “administrators.”

Up to this point, Benedict XVI therefore seemed to attribute the hermeneutic of discontinuity to the Church's progressive current alone. But further on in the address, in analyzing in depth the Council’s intention to “give a new definition to the relationship between the Church and the modern State,” he took up the question on which not the progressives but the traditionalists have stumbled more, to the point of breaking with the Church as the followers of Marcel Lefebvre have done and as Viganò now seems on the point of doing.

It is the question of religious freedom, addressed by the conciliar declaration on religious freedom, Dignitatis Humanae. A declaration that Viganò too charges with the worst of offenses, to the point of writing that “if it has been possible for Pachamama to be worshiped in a church, we owe this to Dignitatis Humanae.

In fact, it is undeniable that on religious freedom Vatican II marked a clear discontinuity, if not a rupture, with the ordinary teaching of the Church of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which was strongly anti-liberal.

Benedict XVI explicitly recognized this in his address and also explained the historical reasons for it, which precisely because they are historical have changed over time and allowed the Council, “recognizing and making its own an essential principle of the modern State with the Decree on Religious Freedom,” to recover “the deepest patrimony of the Church,” that “of Jesus himself” and “of the martyrs of the early Church,” who “died for freedom of conscience and the freedom to profess one's own faith - a profession that no State can impose but which, instead, can only be claimed with God's grace in freedom of conscience.”

“It is precisely in this combination of continuity and discontinuity at different levels that is the very nature of true reform,” Papa Ratzinger said in that address. “The Second Vatican Council, with its new definition of the relationship between the faith of the Church and certain essential elements of modern thought, has reviewed or even corrected certain historical decisions, but in this apparent discontinuity it has actually preserved and deepened her inmost nature and true identity.”

There is therefore a “hermeneutic of discontinuity” which Benedict XVI acknowledged in some way by saying “it is precisely in this combination of continuity and discontinuity at different levels that the very nature of true reform consists.”

But at this point we might as well let him talk and reproduce below the final part of that address of his on the Council, in which he presented at length what has been summarized above in a few lines. Viganò's counterarguments are also available on the websites that cover him. Let the reader compare.

“In this process of innovation in continuity…”

by Benedict XVI

[…] In the great dispute about man which marks the modern epoch, the Council had to focus in particular on the theme of anthropology. It had to question the relationship between the Church and her faith on the one hand, and man and the contemporary world on the other. The question becomes even clearer if, instead of the generic term "contemporary world", we opt for another that is more precise: the Council had to determine in a new way the relationship between the Church and the modern era.

This relationship had a somewhat stormy beginning with the Galileo case. It was then totally interrupted when Kant described "religion within pure reason" and when, in the radical phase of the French Revolution, an image of the State and the human being that practically no longer wanted to allow the Church any room was disseminated.

In the 19th century under Pius IX, the clash between the Church's faith and a radical liberalism and the natural sciences, which also claimed to embrace with their knowledge the whole of reality to its limit, stubbornly proposing to make the "hypothesis of God" superfluous, had elicited from the Church a bitter and radical condemnation of this spirit of the modern age. Thus, it seemed that there was no longer any milieu open to a positive and fruitful understanding, and the rejection by those who felt they were the representatives of the modern era was also drastic.

In the meantime, however, the modern age had also experienced developments. People came to realize that the American Revolution was offering a model of a modern State that differed from the theoretical model with radical tendencies that had emerged during the second phase of the French Revolution.

The natural sciences were beginning to reflect more and more clearly their own limitations imposed by their own method, which, despite achieving great things, was nevertheless unable to grasp the global nature of reality.

So it was that both parties were gradually beginning to open up to each other. In the period between the two World Wars and especially after the Second World War, Catholic statesmen demonstrated that a modern secular State could exist that was not neutral regarding values but alive, drawing from the great ethical sources opened by Christianity.

Catholic social doctrine, as it gradually developed, became an important model between radical liberalism and the Marxist theory of the State. The natural sciences, which without reservation professed a method of their own to which God was barred access, realized ever more clearly that this method did not include the whole of reality. Hence, they once again opened their doors to God, knowing that reality is greater than the naturalistic method and all that it can encompass.

It might be said that three circles of questions had formed which then, at the time of the Second Vatican Council, were expecting an answer.

First of all, the relationship between faith and modern science had to be redefined. Furthermore, this did not only concern the natural sciences but also historical science for, in a certain school, the historical-critical method claimed to have the last word on the interpretation of the Bible and, demanding total exclusivity for its interpretation of Sacred Scripture, was opposed to important points in the interpretation elaborated by the faith of the Church.

Secondly, it was necessary to give a new definition to the relationship between the Church and the modern State that would make room impartially for citizens of various religions and ideologies, merely assuming responsibility for an orderly and tolerant coexistence among them and for the freedom to practise their own religion.

Thirdly, linked more generally to this was the problem of religious tolerance - a question that required a new definition of the relationship between the Christian faith and the world religions. In particular, before the recent crimes of the Nazi regime and, in general, with a retrospective look at a long and difficult history, it was necessary to evaluate and define in a new way the relationship between the Church and the faith of Israel.

These are all subjects of great importance - they were the great themes of the second part of the Council - on which it is impossible to reflect more broadly in this context. It is clear that in all these sectors, which all together form a single problem, some kind of discontinuity might emerge. Indeed, a discontinuity had been revealed but in which, after the various distinctions between concrete historical situations and their requirements had been made, the continuity of principles proved not to have been abandoned. It is easy to miss this fact at a first glance.

It is precisely in this combination of continuity and discontinuity at different levels that the very nature of true reform consists.

In this process of innovation in continuity we must learn to understand more practically than before that the Church's decisions on contingent matters - for example, certain practical forms of liberalism or a free interpretation of the Bible - should necessarily be contingent themselves, precisely because they refer to a specific reality that is changeable in itself.

It was necessary to learn to recognize that in these decisions it is only the principles that express the permanent aspect, since they remain as an undercurrent, motivating decisions from within. On the other hand, not so permanent are the practical forms that depend on the historical situation and are therefore subject to change.

Basic decisions, therefore, can continue to be well-grounded, whereas the way they are applied to new contexts can change.

- Thus, for example, if religious freedom were to be considered an expression of the human inability to discover the truth and thus become a canonization of relativism, then this social and historical necessity is raised inappropriately to the metaphysical level and thus stripped of its true meaning.

- Consequently, it cannot be accepted by those who believe that the human person is capable of knowing the truth about God and, on the basis of the inner dignity of the truth, is bound to this knowledge.

It is quite different, on the other hand, to perceive religious freedom as a need that derives from human coexistence, or indeed, as an intrinsic consequence of the truth that cannot be externally imposed, but that the person must adopt only through the process of conviction.

The Second Vatican Council, recognizing and making its own an essential principle of the modern State with the Decree on Religious Freedom, has recovered the deepest patrimony of the Church. By so doing she can be conscious of being in full harmony with the teaching of Jesus himself (cf. Mt 22:21), as well as with the Church of the martyrs of all time. The ancient Church naturally prayed for the emperors and political leaders out of duty (cf. I Tm 2:2); but while she prayed for the emperors, she refused to worship them and thereby clearly rejected the religion of the State.

The martyrs of the early Church died for their faith in that God who was revealed in Jesus Christ, and for this very reason they also died for freedom of conscience and the freedom to profess one's own faith - a profession that no State can impose but which, instead, can only be claimed with God's grace in freedom of conscience. A missionary Church known for proclaiming her message to all peoples must necessarily work for the freedom of the faith. She desires to transmit the gift of the truth that exists for one and all.

At the same time, she assures peoples and their Governments that she does not wish to destroy their identity and culture by doing so, but to give them, on the contrary, a response which, in their innermost depths, they are waiting for - a response with which the multiplicity of cultures is not lost but instead unity between men and women increases and thus also peace between peoples.

The Second Vatican Council, with its new definition of the relationship between the faith of the Church and certain essential elements of modern thought, has reviewed or even corrected certain historical decisions, but in this apparent discontinuity it has actually preserved and deepened her inmost nature and true identity.

The Church, both before and after the Council, was and is the same Church, one, holy, catholic and apostolic, journeying on through time; she continues "her pilgrimage amid the persecutions of the world and the consolations of God", proclaiming the death of the Lord until he comes (cf. Lumen Gentium, n. 8).

Those who expected that with this fundamental "yes" to the modern era all tensions would be dispelled and that the "openness towards the world" accordingly achieved would transform everything into pure harmony, had underestimated the inner tensions as well as the contradictions inherent in the modern epoch.

They had underestimated the perilous frailty of human nature which has been a threat to human progress in all the periods of history and in every historical constellation. These dangers, with the new possibilities and new power of man over matter and over himself, did not disappear but instead acquired new dimensions: a look at the history of the present day shows this clearly.

In our time too, the Church remains a "sign that will be opposed" (Lk 2,34) - not without reason did Pope John Paul II, then still a Cardinal, give this title to the theme for the Spiritual Exercises he preached in 1976 to Pope Paul VI and the Roman Curia. The Council could not have intended to abolish the Gospel's opposition to human dangers and errors.

On the contrary, it was certainly the Council's intention to overcome erroneous or superfluous contradictions in order to present to our world the requirement of the Gospel in its full greatness and purity.

The steps the Council took towards the modern era which had rather vaguely been presented as "openness to the world", belong in short to the perennial problem of the relationship between faith and reason that is re-emerging in ever new forms. The situation that the Council had to face can certainly be compared to events of previous epochs.

In his First Letter, St Peter urged Christians always to be ready to give an answer (apo-logia) to anyone who asked them for the logos, the reason for their faith (cf. 3,15). This meant that biblical faith had to be discussed and come into contact with Greek culture and learn to recognize through interpretation the separating line but also the convergence and the affinity between them in the one reason, given by God.

When, in the 13th century through the Jewish and Arab philosophers, Aristotelian thought came into contact with Medieval Christianity formed in the Platonic tradition, and faith and reason risked entering an irreconcilable contradiction, it was above all St Thomas Aquinas who mediated the new encounter between faith and Aristotelian philosophy, thereby setting faith in a positive relationship with the form of reason prevalent in his time.

There is no doubt that the wearing dispute between modern reason and the Christian faith, which had begun negatively with the Galileo case, went through many phases, but with the Second Vatican Council the time came when broad new thinking was required.

Its content was certainly only roughly traced in the conciliar texts, but this determined its essential direction, so that the dialogue between reason and faith, particularly important today, found its bearings on the basis of the Second Vatican Council.

This dialogue must now be developed with great openmindedness but also with that clear discernment that the world rightly expects of us in this very moment. Thus, today we can look with gratitude at the Second Vatican Council: if we interpret and implement it guided by a right hermeneutic, it can be and can become increasingly powerful for the ever necessary renewal of the Church.

Rome, December 22, 2005

Viganò replied to Magister twice - first in written answers to LifeSite's John Henry Westen who openly challenged him to say exactly what he meant by his aforementioned critique: Did he believe Vatican II to be an invalid council and thus to be complete repudiated, or if he believes it is a valid council that contained many errors, would the faithful pre-Vatican II magisterium for their spiritual guidance? And second, in a letter to Magister himself. Here first is the LifeSite feature:

Archbishop Viganò: 'I do not think Vatican II

was invalid, but it was gravely manipulated'

[Which is what Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI

has said all along since 1965]

but Vigano concludes we should simply go back

to the Council of Trent]

by John Henry Westen

July 3, 2020

Editor’s note: The following exchange with former USA nuncio Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò is offered in the hopes of clarifying his position on this important matter of consideration in the Church.

Dear Archbishop Viganò,

I am hoping to get a clarification from you about your latest texts regarding the second Vatican council.

In your June 9 text you said that “it is undeniable that from Vatican II onwards a parallel church was built, superimposed over and diametrically opposed to the true Church of Christ.”

In your subsequent interview with Phil Lawler he asked: “What is the solution? Bishop Schneider proposes that a future Pontiff must repudiate errors; Archbishop Viganò finds that inadequate. But then how can the errors be corrected, in a way that maintains the authority of the teaching magisterium?”

You replied: “It will be for one of his Successors, the Vicar of Christ, in the fullness of his apostolic power, to rejoin the thread of Tradition there where it was cut off. This will not be a defeat but an act of truth, humility, and courage. The authority and infallibility of the Successor of the Prince of the Apostles will emerge intact and reconfirmed (bold mine).”

From this it is unclear whether you believe Vatican II to be an invalid council and thus to be complete repudiated or if you believe that while a valid council it contained many errors and the faithful would be better served by having it forgotten about and could rather draw on Vatican I and other councils for their sustenance.

I believe this clarification would be helpful.

In Christ and His beloved Mother,

JH

1 July 2020

In festo Pretiosissimi Sanguinis

Domini Nostri Iesu Christi

Vigano's reply (translated from the Italian by Giuseppe Pellegrini):

Dear John-Henry,

I thank you for your letter, with which you give me the opportunity to clarify what I have already expressed about Vatican II. This delicate argument is involving prominent persons of the ecclesiastical world and not a few erudite laity: I trust that my modest contribution can help to lifting off the blanket of equivocations that weighs on the Council, thus leading to a shared solution.

You begin with my initial observation: “It is undeniable that from Vatican II onwards a parallel church was built, superimposed over and diametrically opposed to the true Church of Christ,” and then quote my words about the solution to the impasse in which we find ourselves today: “It will be for one of his Successors, the Vicar of Christ, in the fullness of his apostolic power, to rejoin the thread of Tradition there where it was cut off. This will not be a defeat but an act of truth, humility, and courage. The authority and infallibility of the Successor of the Prince of the Apostles will emerge intact and reconfirmed.”

You then state that my position is not clear – “whether you believe Vatican II to be an invalid council and thus to be complete repudiated, or if you believe that while a valid council it contained many errors and the faithful would be better served by having it forgotten about.”

I have never thought and even less have I affirmed that Vatican II was an invalid Ecumenical Council: in fact it was convoked by the supreme authority, by the Supreme Pontiff, and all of the Bishops of the world took part in it. Vatican II is a valid Council, supported by the same authority as Vatican I and Trent. However, as I have already written, from its origin it was made the object of a grave manipulation by a fifth column that penetrated into the very heart of the Church that perverted its purposes, as confirmed by the disastrous results that are before everyone’s eyes.

Let us remember that in the French Revolution, the fact that the Estates-General were legitimately convoked on May 5, 1789, by Louis XVI did not prevent things from escalating into the Revolution and the Terror (the comparison is not out of place, since Cardinal Suenens called the conciliar event “the 1789 of the Church”).

In his recent intervention, His Eminence Cardinal Walter Brandmüller maintains that the Council places itself in continuity with the Tradition, and as proof of this he remarks:

It is sufficient to glance at the notes of the text. It can thus be seen that ten previous councils are quoted by the document. Among these, Vatican I is referred to 12 times, and Trent 16 times. From this it is already clear that, for example, any idea of “distancing from Trent” is absolutely excluded.

The relationship with Tradition appears even closer if we think of how, among the popes, Pius XII is cited 55 times, Leo XIII on 17 occasions, and Pius XI in 12 passages. To these are added Benedict XIV, Benedict XV, Pius IX, Pius X, Innocent I and Gelasius. The most impressive aspect, however, is the presence of the Fathers in the texts of Lumen Gentium.

The council refers to the teaching of the Fathers a full 44 times, including Augustine, Ignatius of Antioch, Cyprian, John Chrysostom and Irenaeus. Furthermore, the great theologians and doctors of the Church are cited: Thomas Aquinas in 12 passages, along with seven other heavyweights.

As I pointed out in the analogous case of the Synod of Pistoia, the presence of orthodox content does not exclude the presence of other heretical propositions nor does it mitigate their gravity, nor can the truth be used to hide even only one single error. On the contrary, the numerous citations of other Councils, of magisterial acts or of the Fathers of the Church can precisely serve to conceal, with a malicious intent, the controversial points. In this regard, it is useful to recall the words of the Tractatus de Fide orthodoxa contra Arianos, cited by Leo XIII in his encyclical Satis Cognitum:

There can be nothing more dangerous than those heretics who admit nearly the whole cycle of doctrine, and yet by one word, as with a drop of poison, infect the real and simple faith taught by our Lord and handed down by Apostolic Tradition.

Leo XIII then comments:

The practice of the Church has always been the same, as is shown by the unanimous teaching of the Fathers, who were wont to hold as outside Catholic communion, and alien to the Church, whoever would recede in the least degree from any point of doctrine proposed by her authoritative Magisterium.

On the pages of L’Osservatore Romano, in an article on April 14, 2013, Cardinal Kasper admitted that “in many places [the Council Fathers] had to find formulas of compromise, in which often the positions of the majority (conservatives) are found alongside those of the minority (progressives), designed to delimit them. Therefore, the conciliar texts themselves have an enormous potential for conflict, opening the door to selective reception in both directions.” This is the origin of the relevant ambiguities, patent contradictions, and serious doctrinal and pastoral errors. [And something that was recognized from the time of the Council by many of the theological periti who were consulted [e.g.Joseph Ratzinger and his fellow likeminded Vat-II alumni who together set up Communio, a theological journal to counter Concilio, published by Hans Kueng and his fellow progressivist periti.]

It could be objected that taking into consideration the presumption of malice in a magisterial act ought to be rejected with disdain, since the Magisterium ought to be aimed at confirming the faithful in the Faith; but perhaps it is precisely the intentional fraud that makes an act prove to be non-magisterial and authorizes its condemnation or decrees its nullity. His Eminence Cardinal Brandmüller concluded his comment with these words: “It would be appropriate to avoid the ‘hermeneutic of suspicion’ that accuses the interlocutor from the beginning of heretical conceptions.”

While I surely share this sentiment in the abstract and in general, I think it appropriate to formulate a distinction to better frame this concrete case. In order to do this, it is necessary to abandon the approach that is a bit too legalistic, that considers all doctrinal questions inherent in the Church as reducible and resolvable principally on the basis of a normative reference: let us not forget that the law is at the service of the Truth, and not vice-versa. And the same holds for the Authority that is the minister of that law and custodian of that Truth. On the other hand, when Our Lord faced his Passion, the Synagogue had deserted its proper function as guide of the Chosen People in fidelity to the Covenant, just as part of the Hierarchy has done for sixty years.

This legalistic attitude is at the foundation of the deception of the Innovators, those who devised a very simple way to actuate the Revolution: imposing it by virtue of authority with an act that the Ecclesia docens [the teaching Church] adopted in order to define truths of the Faith with a binding force for the Ecclesia discens [the learning Church], restating that teaching in other equally binding documents, albeit in a different degree.

In short, it was decided to affix the label “Council” to an event conceived by some with the aim of demolishing the Church, and in order to do this the conspirators acted with malicious intent and subversive purposes. [This would seem to place John XXIII among the conspirators as he expressly convened Vatican II as a pastoral council.] Father Edward Schillebeecks candidly said: «We express it diplomatically, but after the Council we will draw the implicit conclusions» (De Bazuin, n.16, 1965).

It is not therefore a question of a “hermeneutic of suspicion,” but on the contrary something much more grave than a suspicion, corroborated by a calm evaluation of the facts, as well as by the admission of the protagonists themselves. In this regard, who among them is more authoritative than then-Cardinal Ratzinger?

The impression grew steadily that nothing was now stable in the Church, that everything was open to revision. More and more the Council appeared to be like a great Church parliament, that could change everything and reshape everything according to its own desires. Very clearly resentment was growing against Rome and against the Curia, which appeared to be the real enemy of everything that was new and progressive. The disputes at the Council were more and more portrayed according to the party model of modern parliamentarism. When information was presented in this way, the person receiving it saw himself compelled to take sides with one of the parties. [...] If the bishops in Rome could change the Church, and even the faith itself (as it appeared they could), why only the bishops? In any event, the faith could be changed – or so it now appeared, in contrast to everything we previously thought. The faith no longer seemed exempt from human decision making but rather was now apparently determined by it. And we knew that the bishops had learned from theologians the new things they were now proposing. For believers, it was a remarkable phenomenon that their bishops seemed to show a different face in Rome from the one they wore at home. (J. Ratzinger, Milestones, Ignatius Press, 1997, pp. 132-133).

[Why then did Vigano portray Benedict XVI in his June 9 manifesto as, in effect, the ringleader of the Vatican II deceivers?]

At this point it is right to draw attention to a recurring paradox in world affairs: the mainstream calls people “conspiracy theorists” if they reveal and denounce the conspiracy that the mainstream itself has devised, in order to divert attention from the conspiracy and delegitimize those who denounce it. Similarly, it seems to me that there is the risk of defining as “hermeneutic of suspicion” anyone who reveals and denounces the conciliar fraud, as if they were people who unjustifiably accuse “the interlocutor from the beginning of heretical conceptions.”

Instead, it is necessary to understand if the action of the protagonists of the Council can justify the suspicion towards them, if not actually prove such suspicion correct; and if whether the result they obtained legitimizes a negative evaluation of the entire Council, of some of its parts, or of none of it.

If we persist in thinking that those who conceived Vatican II as a subversive event rivaled Saint Alphonsus in piety and Saint Thomas in doctrine, we demonstrate a naivety that cannot be reconciled with the evangelical precept, and indeed borders on, if not connivance, then certainly carelessness. [But no one has been that naive - especially since the 'spirit of Vatican II' exponents never masked their subversive intentions.]

Obviously, I am not referring to the majority of Council Fathers, who were certainly animated by pious and holy intentions; I speak instead of the protagonists of the Council-event, of the so-called theologians who up until Vatican II were restricted by canonical censures and forbidden from teaching, and who for this very reason were chosen and promoted and helped, so that their credentials of heterodoxy became a cause of merit for them, while the undisputed orthodoxy of Cardinal Ottaviani and his collaborators in the Holy Office were sufficient reason to consign the preparatory schemae of the Council to the flames, with the consent of John XXIII.

I doubt that with regard to Msgr. Bugnini – to cite only one name – an attitude of prudent suspicion is either censurable or lacking in Charity. On the contrary: the dishonesty of the author of the Novus Ordo in pursuing his purposes, his adherence to Masonry and his own admissions in his diaries given to the press show that the measures taken by Paul VI toward him were all too lenient and ineffective, since everything he did in the Conciliar Commissions and at the Congregation of Rites remained intact and became an integral part of the Acta Concilii and the related reforms. Thus the hermeneutic of suspicion is quite welcome if it serves to demonstrate that there are valid reasons for the suspicion and that these suspicions often materialize in the certainty of intentional fraud.

Let us now return to Vatican II, to demonstrate the trap into which the good Pastors fell, misled into error along with their flock by a most astute work of deception by people notoriously infected by Modernism and not rarely also misled in their own moral conduct. As I wrote above, the fraud lies in having recourse to a Council as a container for a subversive maneuver, and in the utilization of the authority of the Church to impose the doctrinal, moral, liturgical, and spiritual revolution that is ontologically contrary to the purpose for which the Council was called and its magisterial authority was exercised. [From this perspective, Paul VI who ratified all the Vatican II documents, and the 2,500+ Council Fathers - including Marcel Lefebvre who signed all of them although he later denied having signed 'Dignitatis Humanae, the declaration on religious freedom - were all co-conspirators who consciously misused the Council.]

I repeat: the label “Council” affixed to the packaging does not reflect its content. [Which contradicts what he affirms at the start of the answers to Westen:

I have never thought and even less have I affirmed that Vatican II was an invalid Ecumenical Council: in fact it was convoked by the supreme authority, by the Supreme Pontiff, and all of the Bishops of the world took part in it. Vatican II is a valid Council, supported by the same authority as Vatican I and Trent...'

We have witnessed a new and different way of understanding the same words of the Catholic lexicon:

- The expression “ecumenical council” given to the Council of Trent does not coincide with the meaning given by the proponents of Vatican II, for whom the term “council” alludes to “conciliation” and the term “ecumenical” to inter-religious dialogue.

- The “spirit of the council” is the “spirit of conciliation, of compromise,” just as the assembly was a solemn and public attestation of conciliatory dialogue with the world, for the first time in the history of the Church.

Bugnini wrote:

“We must take out of our Catholic prayers and the Catholic liturgy everything which could be the shadow of a stumbling block for our separated brethren, the Protestants” [cf. L’Osservatore Romano, 19 March 1965].

From these words we understand that the intent of the reform that was the fruit of the conciliar mens was to reduce the proclamation of Catholic Truth in order not to offend the heretics: and this is exactly what was done, not only in the Holy Mass – horribly disfigured in the name of ecumenism – but also in the exposition of dogma in the documents of doctrinal content; the use of subsistit in is a very clear example.

Perhaps it will be possible to debate the motives that may have led to this unique event, so fraught with consequences for the Church; but we can no longer deny the evidence and pretend that Vatican II was not something qualitatively different from Vatican I, despite the numerous heroic and documented efforts, even by the highest authority, to interpret it by force as a normal Ecumenical Council.

- Anyone with common sense can see that it is an absurdity to want to interpret a Council, since it is and ought to be a clear and unequivocal norm of Faith and Morals. [Surely none of the preceding 20 ecumenical councils recognized by the Church made decisions and issued decrees which were completely uncontested. Besides, as a 'Spirit of Vatican II' historian observes:

The first twenty Councils were called to settle particular problems (usually doctrinal), or for disciplinary purposes. The sole exception is Vatican II which was called to examine the Church itself and this developed, rationally, into a consideration of the Church in relation to the world it serves.

- Secondarily, if a magisterial act raises serious and reasoned arguments that it may be lacking in doctrinal coherence with magisterial acts that have preceded it, it is evident that the condemnation of a single heterodox point in any case discredits the entire document.

- If we add to this the fact that the errors formulated or left obliquely to be understood between the lines are not limited to one or two cases, and that the errors affirmed correspond conversely to an enormous mass of truths that are not confirmed, we can ask ourselves whether it may be right to expunge the last assembly from the catalog of canonical Councils. [In other words, to invalidate it completely. Probably an impossible task, if only because no previous council recognized by the Church has been invalidated. And that it would take another council to invalidate, or even to simply correct, anything that Vatican II decreed.]

The sentence will be issued by history and by the sensus fidei of the Christian people even before it is given by an official document. The tree is judged by its fruits, and it is not enough to speak of a conciliar springtime to hide the harsh winter that grips the Church; nor to invent married priests and deaconesses in order to remedy the collapse of vocations; nor to adapt the Gospel to the modern mentality in order to gain more consensus. The Christian life is a militia, not a nice outing in the country, and this is all the more true for priestly life.

I conclude with a request to those who are profitably intervening in the debate about the Council: I would like us first and foremost to seek to proclaim salvific Truth to all men, because their and our eternal salvation depends on it; and that we only secondarily concern ourselves with the canonical and juridical implications raised by Vatican II: anathema sit or damnatio memoriae, it changes little. [Then, what is to be done?]

If the Council truly did not change anything of our Faith [a premise which the progressivists reject, for the simple reason that they believe Vatican II did establish a new 'Church'.], then let us pick up the Catechism of Saint Pius X, return to the Missal of Saint Pius V*, remain before the Tabernacle, not desert the Confessional, and practice penance and mortification with a spirit of reparation. This is whence the eternal youthfulness of the Spirit springs. And above all: let us do so in such a way that our works give solid and coherent witness to what we preach.

*[In effect, Viganò would have us go back to the 16th-century Council of Trent, which John XXIII, in convening Vatican II, wished the Church to go beyond being 'somewhat inward-looking and static for 400 years since the Council of Trent' whereas, the catalogue of global changes since the 16th century is vast and involves greater understanding of the universe, of other cultures and of mankind itself].

+ Carlo Maria Viganò, Archbishop

I have to translate Magister's blogpost in which he publishes Vigano's letter to him, and a recent lecture in Rome by Cardinal Brandmueller on the difficulties of 'interpreting' Vatican II.[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 10/07/2020 02:59] |