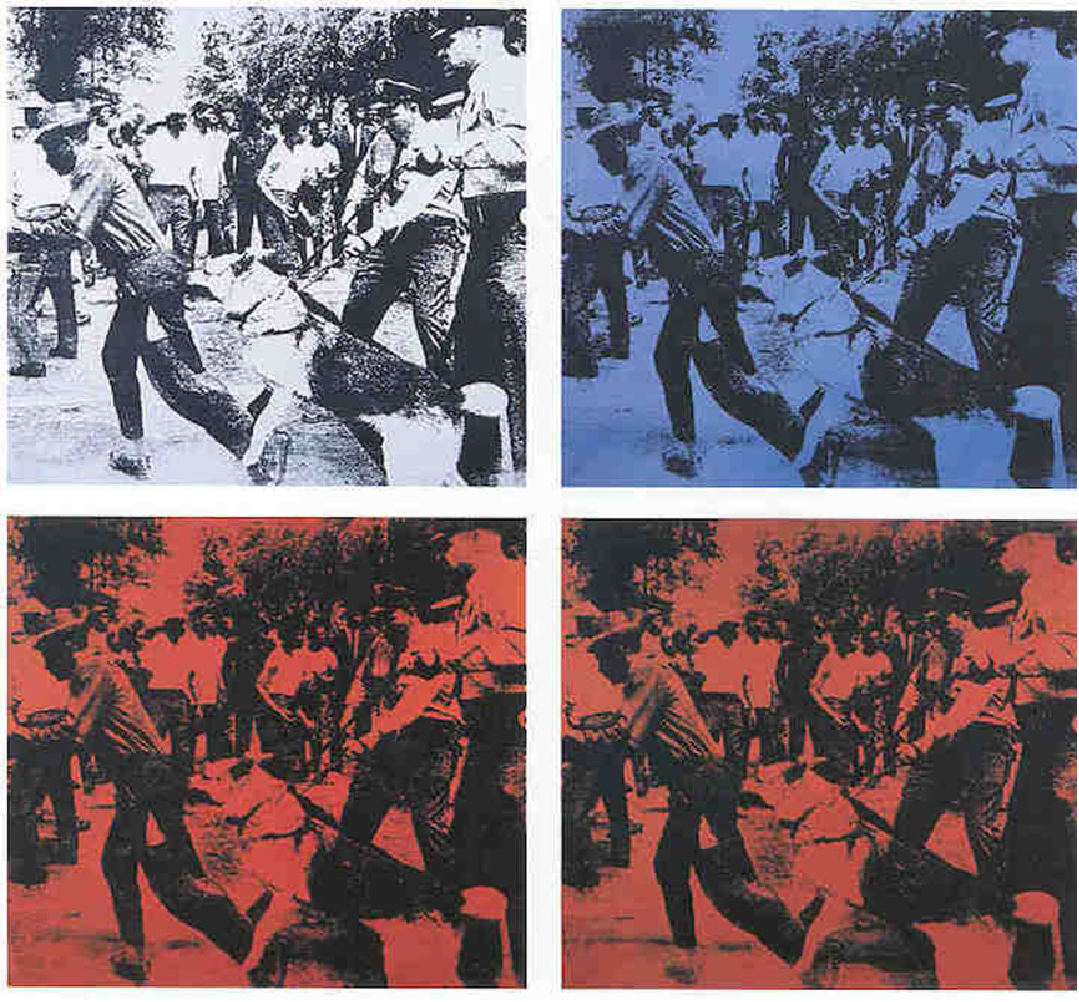

Race Riot by Andy Warhol, 1964 [private collection]. The painting, was originally part of a Paris show called Death in America. Race Riot sold in a 2014 New York auction for $62,885,000. Imagine that!

A refreshing take on the current international hysteria about 'racism in America' from someone who grew up white and unDder-privileged. Because in the USA as elsewhere,

Race Riot by Andy Warhol, 1964 [private collection]. The painting, was originally part of a Paris show called Death in America. Race Riot sold in a 2014 New York auction for $62,885,000. Imagine that!

A refreshing take on the current international hysteria about 'racism in America' from someone who grew up white and unDder-privileged. Because in the USA as elsewhere,

privilege is a prerogative of those who do not want for the means to live a minimally decent life. Black, white, brown or yellow, everyone who is poor is under-

privileged or without privilege. The 'American dream' as it used to called was precisely the realistic aspiration that in the USA, individuals have the opportunity to rise above

the circumstances into which they are born, and that millions have done so.

'White privilege' and other matters

by David Carlin

June 12, 2020

I grew up the beneficiary of white privilege. It was my “privilege” to spend my first fifteen years in a cold-water tenement at 131 Beverage Hill Avenue in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. There was no central heating. The tenement was heated by the same kitchen stove on which the cooking was done.

If you wanted to wash your hands or face in warm water, you had to heat a bucket of water on the stove and then pour it into a sink. If you wanted a warm bath, you had to heat many buckets of water and pour them into the bathtub. There was of course no shower.

In the winter, to conserve heat, you closed off the front room of the tenement. The kitchen became our all-purpose room. To replenish the fuel that supplied the heating segment of our stove, you went down to the basement, filled a container with kerosene, then walked up two flights of stairs.

When my young sister needed medical treatment, we had the “privilege” of selling our old second-hand (or was it third-hand?) car, and then living for years without an automobile. But this in turn gave us the “privilege” of riding the bus to downtown Pawtucket to do our shopping. On Friday evenings my mother and I would go to one of the supermarkets then located in downtown Pawtucket, and I, a shrimp of a lad, had the “privilege” of lugging heavy grocery bags back home on the bus. My mother had the same “privilege.”

Around 1950, my father suffered a crippling attack of arthritis that kept him out of work and often in bed for a year. At that time we had the “privilege” of slipping from near-poverty into downright poverty. Fortunately, almost miraculously, my father recovered, and as soon as he did he got a job and went back to work, traveling via three buses from our home to his workplace at the distant western edge of Providence.

But in addition to my many “privileges,” I had some real advantages growing up in Pawtucket. First and foremost, I had two married parents with a very strong sense of parental duty. They worked hard, they played by the rules, they put family above individual self.

Second, I had Pawtucket public schools: Prospect Street School and Goff Junior High School. The teachers, the great majority of them unmarried women, were marvelous. They stuffed my head with knowledge and, more importantly, the desire for further knowledge.

Later, when my family had rebounded from poverty and could afford to pay the $100 annual tuition, I went to St. Raphael Academy, a Christian Brothers school with marvelous teachers. (The tuition now is well over $10,000 per annum; and there are no longer any Christian Brothers there.)

Third, I had the Catholic religion and its many Pawtucket churches.

The religion reinforced the lessons in good conduct that I had learned at home and at school. It taught me to behave myself, and it taught me to feel guilty when my behavior fell below ideal standards (which it sometimes still does).

Fourth, I had the Pawtucket Boys’ Club, which supplied me with friends and with good clean recreation.

Finally, I had the city of Pawtucket itself – “the birthplace of the American industrial revolution,” for it was here that America’s first textile factory was built in 1790. In my boyhood (the 1940s and ‘50s) Pawtucket was in the last stages of what may be called its golden age. It was a splendid city for a boy to grow up in – a blue-collar city just right for boys from blue-collar families.

Downtown Pawtucket was vibrant, filled with people and stores and banks and restaurants and movie theaters – plus the Boys’ Club. (Nowadays downtown is a ghost town). The streets were safe. Violence rarely went beyond an occasional fistfight. Even though much of the city was densely packed with tenement houses, there always seemed to be plenty of room for kids to play.

Everybody who is not a complete idiot knows and admits that America has a long and horrible history of anti-black racism – 250 years of slavery and 100 years of post-emancipation racial segregation. And everybody, not just virtuous liberals, deplores that history. But everybody who is not self-deceived also knows that white racism is at most a minor factor in the misery that prevails today in much of black America.

If blacks, on average, are worse off than the average white in almost every category of well-being – health, income, education, jobs, and many others – this is chiefly because of an appallingly dysfunctional culture that is pervasive among the black lower classes and tends even to “percolate” upwards into the black middle classes.

This culture fosters and condones attitudes that lead to astronomical rates of out-of-wedlock births (more than 70 percent of black births are to unmarried women), millions of fathers who give little or no support to their children, high rates of crime and violence, high levels of drug abuse, a poor work ethic, very poor academic achievement.

Unless these aspects of the culture are reformed and healed, we may expect that great numbers of blacks will live in misery for the next few hundred years.

The greatest enemies of American blacks today are, in my humble opinion, white liberals who have a vested interest in keeping alive the myth of white racism. White liberals – who by and large are truly privileged, having good educations, jobs, incomes, houses, cars, wine, coffee, etc. – like to believe that all whites other than themselves are racists. For this allows white liberals to feel morally superior to everybody else.

And so white liberals – who dominate the “command posts” of American moral propaganda (the mainstream media, the entertainment industry, and our leading colleges and universities – are endlessly telling blacks that they are the victims of white racism, thus encouraging blacks to feel powerless, angry, and resentful, and diverting them from focusing on their real problem, a dysfunctional subculture.

Dear God, send us some truth.

David Carlin is a retired professor of sociology and philosophy at the Community College of Rhode Island, and the author of The Decline and Fall of the Catholic Church in America.

Another Catholic Thing reflection on the topic...

Are these not my people?

George Floyd and his white murderer,

Donald Trump and the rioters ,

slaveowner and slave -

they are all Americans

by Stephen P. White

June 11, 2020

When the bishops of the United States issued

their first pastoral letter on racism in forty years, titled “Open Wide Our Hearts,” in November of 2018, it was not front-page news. At the time, the Church in the United States was reeling from the McCarrick scandal, the Pennsylvania grand jury report, and the Viganò testimony.

The big story from that week’s meeting in Baltimore was that the bishops’ plans to vote on accountability measures for episcopal malfeasance had been forestalled at the request of Rome.

As sadly prescient as it may seem today, the pastoral letter may not have made much of a splash even if it had not been drowned out by other headlines. Americans do not particularly like thinking about racism – and here I will venture to say that this is especially true of the large majority of Americans who happen to be white. For one, racism is ugly. More than that, Americans are exceptionally bad at talking about it.

We are bad at talking about race, in part, because we do not trust each other – a fact that for some reason we are not supposed to admit. Racial differences, inextricably intertwined with cultural and class differences, make some Americans visually and unmistakably distinct from other Americans.

I do not need to point out to any African-American that he is part of a racial minority. Nor do I need to point out to him that I am not. Nor do I need to explain that the minority to which he belongs has suffered terribly in this country, in myriad ways, for centuries, mostly at the hands of people who look like more like me than like him.

I don’t assume when I meet a black person that he distrusts me. But neither would I be surprised nor upset to find that his trust is less easily won on account of our differences. Nor do I think he would be the least bit surprised to learn that, for a great many white Americans, the feeling is mutual.

Such a lack of trust is not racism – though it can be a breeding ground for it – but it is a barrier to honesty. And it is hard to have meaningful conversations without that. Not wanting to admit a trust deficit between Americans of different races (and it’s mostly white people who don’t want to admit it, for fear of sounding racist) doesn’t make things any easier.

A second reason we Americans are terrible at talking about race is related to the first.

We have become confused about how to speak sensibly and truthfully to one another as members of communities. We lack a clear sense of just what it is we belong to and, thus, lack a clear sense of what and to whom we owe in justice. (Identity politics has made this problem worse, I believe, but it has not caused it. Identity politics can be understood as a misguided attempt to resolve it.)

There is a natural tendency to seek solidarity with others in a moment of crisis. The masses of Americans marching in protest of the killing of George Floyd show this impulse to solidarity. Then again, so do the police unions.

Solidarity joins people together, but it also, in practice, always divides as well. A lot depends on whom one sees as “one’s own.”

It is natural to seek refuge in solidarity. We take pride in the triumphs of the communities to which we belong. We also share responsibility.

This idea – that we are somehow both responsible to and responsible for the communities to which we belong – has largely been choked out by an ethos of individualism. The idea of collective guilt offends our American sensibilities. (Collective triumph, we’re OK with: USA! USA! USA!)

But the notion of collective responsibility – of “social sin,” to use a much-maligned phrase – ought not to be foreign to anyone familiar with Scripture. God judges us as individuals, yes, but also as members of peoples, assigning guilt and judging grievance both personally and corporately.

The price of the sin of Adam and Eve is paid by all their descendants. The sin of Cain, likewise. The repentance of Nineveh, the plagues against Egypt, Israel wandering the wilderness of Sinai, the Babylonian Exile –

the Scriptures are filled with examples of people being made to share in punishment for sins on behalf of the peoples of which they are part.

There is another side to this as well. As Abraham asked, as he pleaded with the Lord to spare the city of Sodom for the sake of ten good men, “Will you really sweep away the righteous with the wicked?”

Above all, there is the example of Christ himself, offering himself as one sacrifice for the sins of all.

The point here is this:

-

Perhaps one problem with our conversations about race is that we want to have things both ways – to heal as one without accepting any responsibility for a whole.

- We want to proclaim ourselves one people, but without taking responsibility for the parts to which we do not wish to belong.

- We treat the healing of one people as a meeting of many nations. We don’t belong to one another.

As a descendant of Irish Catholics, I’d rather not take responsibility for the sins of English Protestants who owned slaves. As a resident of Virginia, I’d rather not be blamed for the sins of that cop in Minnesota who murdered George Floyd.

As an American, though? Are these not my people? The slave owner and the slave . . . the white police officer and Mr. George Floyd?

What makes us think we get to pick and choose?

That is not just a rhetorical question. I think it is a hard question and one with serious implications. How we answer it will determine a lot about how our national conversation about race plays out this time.

Stephen P. White is executive director of The Catholic Project at The Catholic University of America and a fellow in Catholic Studies at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 15/06/2020 04:31]