Xavier Rynne II's February 21 letter from the Vatican has to do with St Peter Damian, Doctor of the Church and scourge of clerical sex offenses, whose feast we celebrate today, the day providentially - but perhaps unknowingly - chosen by Pope Francis to begin his summit on clerical sex abuse...

Remembering St. Peter Damian

Xavier Rynne II's February 21 letter from the Vatican has to do with St Peter Damian, Doctor of the Church and scourge of clerical sex offenses, whose feast we celebrate today, the day providentially - but perhaps unknowingly - chosen by Pope Francis to begin his summit on clerical sex abuse...

Remembering St. Peter Damian

by Xavier Rynne II

Letter from the Vatican #3

February 21,2019

Grant, we pray, almighty God, that we may so follow the teaching and example of the Bishop Saint Peter Damian, that, putting nothing before Christ, and always ardent in the service of your Church, we may be led to the joys of eternal light. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Whether accidental or deliberate, the fact that a world meeting of Catholic leaders to address the scourge of clerical sexual abuse is opening on today’s liturgical memorial of St. Peter Damian is certainly appropriate. That coincidence could also prove providential, if those participating in the discussions of the next four days take the example of this Doctor of the Church seriously and apply his candor, tenacity, and courage to our own times.

Born in Ravenna in 1007, Peter Damian was well-educated in the humanities and pursued a career as a teacher before taking Holy Orders and then entering the monastery at Fonte Avellana in 1035. Elected prior in 1043, he led a reformed monastic community that lived from the insights of both St. Benedict and St. Romuald, combining traditional aspects of monasticism with the more rigorous disciplines of hermits.

After reforming the life of his own community, he devoted himself to reforming the clergy as a whole, working with several popes but especially Leo IX. Created cardinal against his will by Pope Stephen IX, he also undertook direct pastoral duties as archbishop of Ostia, one of the “suburbicarian” dioceses held by the senior members of the College of Cardinals.

In 1067, Pope Alexander II allowed him to return to his preferred life at Fonte Avellana, although he continued to undertake diplomatic missions for the Holy See. He died in 1072 and was declared a Doctor of the Church in 1828 by Pope Leo XII. As Pope Benedict XVI said of Damian, “He spent himself with lucid consistency and great severity for the reform of the Church of his time.”

And the Church of the eleventh century was in desperate need of reform. Much of it was an ungodly mess, not unlike Western Europe itself, which had suffered under decades of depredations by various invaders, including Vikings, Muslims, and Magyars.

Intellectual and cultural life had eroded, to the point where, as one author puts it, “the literary patrimony of Latin antiquity maintained a tenuous presence in the care of monasteries and diocesan libraries,” which had themselves been assaulted by invading marauders with no regard for learning. Commercial life was similarly broken and poverty was as widespread as ignorance.

The papacy had been in crisis for well over a hundred years, sometimes a pawn and sometimes a player in the power struggles that convulsed Italy. Corrupt laity deposed popes and installed their preferred candidates, some of whose parentage was, to put it discreetly, dubious. One pope of the early tenth century, John XII, was said to live in a “pigsty of lust” and died at age 26.

This turmoil had a deeply corrosive effect on clerical discipline. As Matthew Cullinan Hoffman

[who published an English translation of Liber Gomorrhianus last year] writes,

“The ranks of the monasteries and secular priesthood had been adulterated with lax and uneducated men, unworthy of their office. Corruption was rife, and the offices of the clergy, including bishoprics, were often sold. Many priests violated the Church’s strictures against sacerdotal marriage by entering into illicit unions with wives or concubines, with the consent and even approval of their flocks. Large numbers had succumbed to unnatural sexual practices, all of which fell under the dread name of ‘sodomy,’ in reference to the city of Sodom destroyed by God in the book of Genesis.”

Peter Damian, a true ascetic, was not just appalled by “sodomy,” which in those days was a term covering a range of sins against chastity; he decided to do something about it.

- His campaign for the reform of the clergy was carried on by a variety of means, including preaching, teaching, and confronting ecclesiastical authorities — including the highest.

- He also wrote

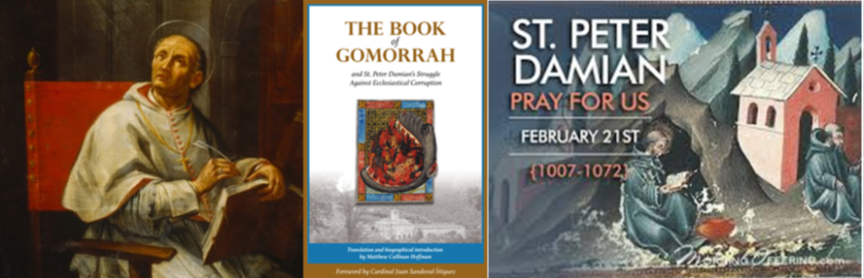

The Book of Gomorrah, a series of brief essays which was based on his appeals to Pope Stephen IX to undertake a massive reform of the clergy.

The Book of Gomorrah remains in print, and while it constitutes some very chilling reading, its brutal candor about clerical sexual corruption and its insistence on the imperative of clerical sexual discipline for the Church’s well-being have considerable resonance today, almost a millennium after Damian wrote.

And while twenty-first-century Church leaders may think (with some reason) that we have a more thorough understanding of the often-roiling dynamics of human sexuality than was available to the cardinal archbishop of Ostia in the mid-eleventh century, everyone participating in this week’s Vatican abuse summit can learn from St. Peter Damian’s unflinching honesty about the crisis of the Church in his time, and from his conviction that

the truths embedded in the Sixth Commandment are not negotiable —in his time or any other time.

It is not easy to imagine, for example, that Damian would have been pleased with the “statement” released a few days ago, in anticipation of the abuse summit, by the Unions of Superiors General (of religious men and women in consecrated life).

No one could quibble with what was obviously intended to be the money quote from this document: “The abuse of children is wrong anywhere and anytime: this point is not negotiable.” That is the ultimate no-brainer. The Unions’ statement also made unexceptionable pledges about outreach to victims, improvement of religious formation, and the importance of a deeper conversion of hearts, minds, and souls.

-

But nowhere in the statement was there any acknowledgement of the violations of chastity that are still rife in various congregations of consecrated life, some of which have decimated those communities (not least through the scourge of AIDS).[/B

- Nor did the Unions reckon with the fact that more than a few consecrated religious men and women have been major contributors to the culture of theological dissent that has, at the very least, been one factor in religious superiors’ blindness to sexual dysfunction within their communities, and one facilitator of sexual abuse by those who once formally promised poverty, chastity, and obedience of God and the Church.

- Nor did the Unions’ statement get beyond the “protection of minors” issue to the larger crisis of chastity throughout the world Church. Peter Damian believed that the truths that Catholic moral reason had learned from the Sixth Commandment, however difficult to live, were true “anywhere and anytime”; there is no affirmation of that non-negotiability in the Unions’ statement.

St. Peter Damian’s is not the only voice to be heard as the Catholic Church wrestles with the challenge of chastity, especially for its ordained leaders, in the hyper-sexualized twenty-first century.

But it is precisely the cleansing harshness of his critique — the prophetic harshness of a John the Baptist — that makes his one voice to be reckoned with. And whatever the limits of his method of argument, his bracing if jarring example of clear-eyed honesty about the facts is one that must be followed, if this abuse summit is going to be a step toward authentic and deep Catholic reform.

February 21, Feast of St Peter Damian -

a prophet for today's Church

February 21, 2019

Incredible but true. This very day, February 21, the day on which Pope Francis is inaugurating the summit on sexual abuse with the leaders of the Catholic hierarchy worldwide, the Church celebrates the liturgical memory of Saint Peter Damian, a great reformer of the 11th century, later proclaimed a Ddoctor of the Church, the author of a book with an emblematic title:,

Liber Gomorrhianus [Book of Gomorrah].

The coincidence, as unintentional as it may be, could not have been more appropriate. Because in that book, composed in the form of a letter,

Saint Peter Damian launched a dramatic appeal to the pope and bishops of his time, that they free the Church from the “sodomitic filth that insinuates itself like a cancer in the ecclesiastical order, or rather like a bloodthirsty beast rampaging through the flock of Christ.” Sodom and Gomorrah, in the book of Genesis, are the two cities that God destroyed with fire on account of their sins of sex against nature.

But there’s more. Because the German Church historian Walter Brandmüller, who recently has done the most to bring to light the extraordinary similarities between the crisis of the Church in the 11th century and the contemporary crisis, is also the cardinal who in the run-up to this summit signed, along with fellow cardinal Raymond Leo Burke, a letter-appeal to the bishops of the whole world that they break the silence and finally face head-on the plague of homosexual activity among sacred ministers.

Last November 5, in conjunction with the release of the essay by Cardinal Brandmüller on the relevance of Saint Peter Damian’s life and times, Settimo Cielo published an ample summary of it, with references to the complete text in German and Italian.

What follows is that very post, which more than ever is worth rereading today, on the day of the liturgical feast of that great saint and reformer.

Gomorrah in the 21st Century:

The appeal of a cardinal and Church historian

Appeal of a Cardinal and Church Historian

“The situation is comparable to that of the Church in the 11th and 12th century.” As an authoritative Church historian and as president of the Pontifical Committee of Historical Sciences from 1998 to 2009, Cardinal Walter Brandmüller, 89, has no doubt when he sees the present-day Church “shaken to its foundations” on account of the spread of sexual abuse and homosexuality “in an almost epidemic manner among the clergy and even in the hierarchy.”

“How could it have come to this point?” the cardinal wonders. And his answer is found in an extensive and detailed article published in recent days in the German monthly

Vatikan Magazin edited by Guido Horst:

> Homosexualität und Missbrauch - Der Krise begegnen: Lehren aus der Geschichte

(Homosexuality and abuses: Confront the crisis - learn from history)

Brandmüller refers to the centuries in which the bishoprics and the papacy itself had become such a source of wealth that there was “fighting and haggling over them,” with temporal rulers claiming that they themselves could apportion these offices in the Church.

The effect was that the place of pastors was taken by morally dissolute persons who were attached to material endowment rather than to the care of souls, by no means inclined to lead a chaste and virtuous life.

Not only concubinage, but homosexuality too was increasingly widespread among the clergy, to such an extent that Saint Peter Damian in 1049 delivered to the newly elected pope Leo IX, known as a zealous reformer, his

Liber Gomorrhianus, composed in the form of a letter, which in essence was an appeal to save the Church from the “sodomitic filth that insinuates itself like a cancer in the ecclesiastical order, or rather like a bloodthirsty beast rampaging through the flock of Christ.” Sodom and Gomorrah, in the book of Genesis, are the two cities that God destroyed with fire on account of their sins.

But the thing more worthy of note, Brandmüller writes, was that “almost simultaneously a lay movement arose that was aimed not only against the immorality of the clergy but also against the appropriation of ecclesiastical offices by secular powers.”

“What rose up was the vast popular movement called

pataria, led by members of the Milanese nobility and by some members of the clergy, but supported by the people. In close collaboration with the reformers associated with Saint Peter Damian, and then with Gregory VII, with the bishop Anselm of Lucca, an important canonist who later became Pope Alexander II, and with others still, the

patarini demanded, even resorting to violence, the implementation of

the reform that after Gregory VII took the name ‘Gregorian’: for a celibacy of the clergy lived out faithfully and against the occupation of dioceses by secular powers.”

Subsequently, of course, it dispersed into pauperist and anti-hierarchical movements, on the verge of heresy, and was only partially reintegrated with the Church “thanks to the farseeing pastoral action of Innocence III.” But the “interesting aspect” on which Brandmüller insists is that

“the reforming movement broke out almost simultaneously in the uppermost hierarchical circles in Rome and among the vast lay population of Lombardy, in response to a situation considered unbearable.”

So then, what is similar and different in the Church today, with respect to back then?

What is similar, Brandmüller notes, is that then as now the ones expressing the protest and demanding a purification of the Church are above all segments of the Catholic laity, especially in North America, in the footsteps of the “marvelous homage to the important role of the witness of the faithful in matters of doctrine” brought to light in the 19th century by Blessed John Henry Newman.

Then as now, these faithful find beside them a few zealous pastors. But

it must be recognized - Brandmüller writes - that the impassioned appeal to the upper hierarchy of the Church and ultimately to the pope to join them in combating the scourge of homosexuality among the clergy and the bishops is not meeting with correspondingly adequate responses, unlike in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Also in the Christological battles of the 4th century - Brandmüller points out -

“the episcopacy remained inactive for long stretches.” And if it remains so today, with respect to the spread of homosexuality among sacred ministers, “this could be based on the fact that personal initiative and the awareness of their responsibility as pastors on the part of the individual bishops are made more difficult by the structures and apparatus of the episcopal conferences, with the pretext of collegiality or synodality.”

As for the pope, Brandmüller attributes not only to the current one but also to his predecessors the weakness of not opposing the currents of moral theology according to which “what was forbidden yesterday can be allowed today,” homosexual acts included.

It is true - Brandmüller acknowledges - that the 1993 encyclical “Veritatis Splendor” of John Paul II - “in which the contribution of Joseph Ratzinger has not yet been duly recognized” - reconfirmed “with great clarity the foundations of the Church’s moral teaching.” But this “ran up against widespread rejection from theologians, perhaps because it had been published only when the theological-moral decay was already too far advanced.”

It is also true that “some books on sexual morality were condemned” and “two professors had their teaching licenses revoked, in 1972 and 1986.”

“But,” Brandmüller continues, “the truly important heretics, like the Jesuit Josef Fuchs, who from 1954 to 1982 was a professor at the Pontifical Gregorian University, and Bernhard Häring, who taught at the Redemptorist Institute in Rome, as well as the highly influential moral theologian from Bonn, Franz Böckle, or from Tübingen, Alfons Auer, were able to spread without interference, right in front of Rome and the bishops, the seed of error.

The attitude of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in these cases is, in retrospect, simply incomprehensible. It saw the wolf come and stood looking on while it ravaged the fold.”

[This is a most disturbing accusation. Did the cardinal look into the records of the CDF to see what measures were taken about the theologians he mentions, whether investigations were made and what these were, and the possibility that the investigations showed their writings, however 'heterodox', did not merit formal sanctions? Or perhaps lesser sanctions were issued through the theologians' local bishops? I am more than surprised - and disappointed - that Sandro Magister did not take the initiative to look into this, considering the enormity of the accusation Brandmueller made against the CDF,about which he did not even comment.

Brandmueller, a friend and near contemporary of Benedict XVI, who made him a cardinal in 2010, owes us an explanation. At the time he wrote this article on Peter Damian, he had had six years during which to ask Benedict XVI directly why the theologians he mentions were not disciplined by the CDF, assuming he never asked him before (and if he did not, then why not?)

If he did not, then he is doing what he did when in 2017, he publicly criticised Benedict XVI for his renunciation and for the provisions he made as to how he would carry on as emeritus pope - when it would have been more proper for him to discuss this with his friend first and then also state his side of the issue in the denunciation he published. Obviously he did not, which is why the usually gentle and forbearing Benedict XVI wrote to reproach him privately.]

The risk is that on account of this lack of initiative on the accusation of the upper hierarchy even the most committed Catholic laity, left on its own, might “no longer recognize the nature of the Church founded on the sacred order and slip, in protesting against the ineptitude of the hierarchy, into an Evangelical-style communitarian Christianity.”

And instead, the more the hierarchy, from the pope down, feel supported by the effective resolve of the faithful to renew and revive the Church, the more a true housecleaning can be performed.

Brandmüller concludes: “It is in the collaboration of the bishops, priests, and faithful, in the power of the Holy Spirit, that the current crisis can and must become the point of departure for the spiritual renewal - and therefore also for the new evangelization - of a post-Christian society.”

Brandmüller is one of the four cardinals who in 2016 submitted to Pope Francis their “dubia” on the changes being made in the doctrine of the Church, without ever receiving a response.

This time will the pope listen and take him seriously into consideration, as Leo IX did with Saint Peter Damian?

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 21/02/2019 16:42]