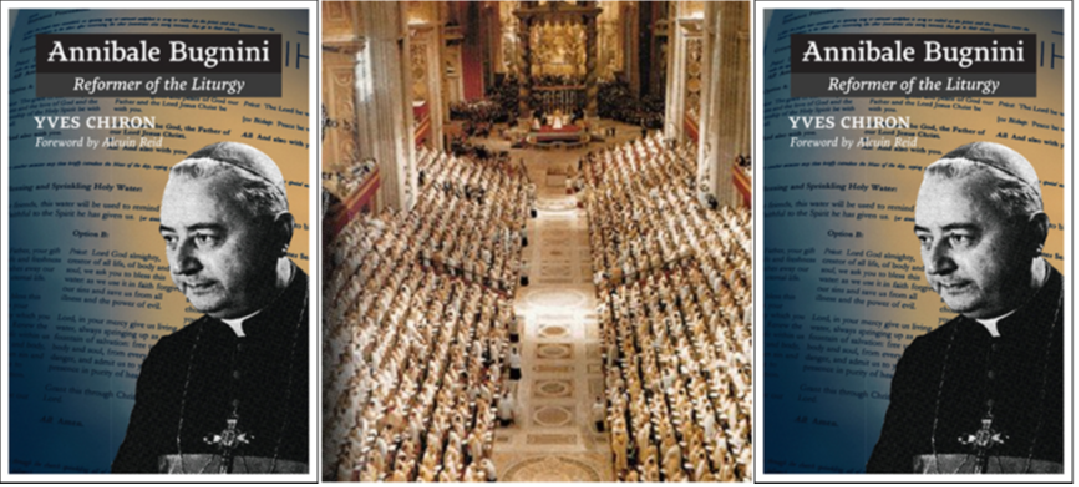

Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy

Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy

by Yves Chiron

Foreword by Alcuin Reid

Angelico Press, 2018 (214 pp)

Lament for the liturgy

The book on Bugnini is indispensable both for its historical depth and breadth but also

to understand how we received the only liturgy that most Roman Catholics have ever experienced.

by Conor Dugan

January 27, 2019

Fifty years ago this April, Pope St. Paul VI issued the Apostolic Constitution, Missale Romanum, which promulgated the Novus Ordo Missae, the New Rite of the Roman Mass. The Novus Ordo went into effect the first Sunday of Advent, November 30, 1969.

This new missal was the culmination of efforts set into motion by the first of the four constitutions promulgated by the Second Vatican Council,

Sacrosanctum Concilium, which called for the Latin Rite’s “liturgical books . . . to be revised as soon as possible”, to employ “experts . . . on the task”, and to consult the bishops of various parts of the world in the revisions.

To say that the faithful’s experience of worship changed in the period from 1963 through 1969

[Actually, the change took place in 1969, because until then, the traditional Mass was still used everywhere] is an understatement. The language, gestures, orientation, and much else in the Mass changed — sometimes overnight

[All this did change literally overnight!]

- How did the Church go from the Sacrosanctum Concilium to the Novus Ordo?

- What was the process that led from that Constitution, promulgated on November 22, 1963, to the Novus Ordo that went into effect just six years later?

- It is to these questions that Yves Chiron, a noted-French historian and writer, directs himself in his newly-translated book

Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy.

The late-Archbishop Bugnini, was the Italian Vincentian who served as the influential secretary of the

Consilium ad exsequendam Constiutionem de Sacra Liturgia (the Committee for the Implementation of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy). Chiron’s work is both a biography of Bugnini and a succinct overview of the Consilium’s work in implementing and imposing the liturgical reform that gave us the Novus Ordo and the current Liturgy of the Hours.

Chiron’s work is inequal parts impressive and depressing.

- It is impressive because Chiron avoids both polarizing starting points and conclusions, shows a great command of the primary sources, and in under 200 pages gives a succinct overview of the Consilium’s work.

- Chiron’s biography is a sober, objective, and well-researched account. His Bugnini is no bogeyman.

- It is depressing because the book gives an unvarnished window into the political machinations, processes, and frequent failings behind the liturgical reform.

In reading Chiron’s book, one understands at a deep level Joseph Ratzinger’s trenchant but charitable critiques of the post-Vatican II liturgical reform. For instance, in his 1998 memoir Milestones, Ratzinger wrote:

It was reasonable and right of the Council to order a revision of the missal such as had often taken place . . . But more than this now happened: the old building was demolished, and another was built . . . Setting [the Novus Ordo] as a new construction over against what had grown historically, forbidding the results of this historical growth, thereby makes the liturgy appear to be no longer a living development but the product of erudite work and juridical authority; this has caused us enormous harm. For then the impression had to emerge that liturgy is something “made,” not something given in advance.

Indeed, this book helps one understand why Ratzinger has stated that

“with respect to the Liturgy,” the Pope “has the task of a gardener, not that of a technician who builds new machines and throws the old ones on the junk-pile.”

Chiron’s book shows that the Consilium’s work too often was that of a technician rather than a gardener. In Chiron’s account we see the (self-inflicted) wound that continues to harm the Church to this day. Chiron’s book is indispensable both for its historical depth and breadth but also for understanding how we received the only liturgy that most Roman Catholics have ever experienced.

Bugnini’s early years

Bugnini was born to a pious Italian family in the Umbrian hills ,and like two of his siblings entered religious life, joining the Vincentians. As young priest, Bugnini was a liturgical innovator. He experimented with the dialogue Mass, something that had already become relatively common. The dialogue Mass consisted of “the faithful reciting the ‘responses and prayers’ that were otherwise said by the server(s).” But Bugnini went beyond this, having “the assembly say aloud a sort of paraphrase of the text of the Mass.”

Bugnini’s words concerning his achievement are revealing of a mindset that would come to dominate the liturgical reform:

“The ‘inert and mute’ assembly had been transformed into a living and prayerful assembly.” Bugnini viewed active participation — what some would say is better described as actual participation — as equal to or at the very least primarily expressed through verbal actions — speaking and responding.

This view of participation sees it not primarily as an inner phenomenon, by which the faithful enter more deeply into the mystery of Christ’s Incarnation, death, and Resurrection, made present in the liturgy, but rather something manifested by outward actions and demonstrations.

When Bugnini became editor of the Vincentian liturgical journal Ephemerides Liturgicae

, he had a platform from which to “broadcast his ideas for a liturgical reform.” Like so many other tasks to which Bugnini put his energies, the journal, which had been moribund, began to flourish. Bugnini commissioned a survey of liturgical needs and desires. The survey was generated by

Bugnini’s wish to “rejuvenate the liturgy, ‘ridding’ it of the superstructures that weighed it down over the centuries.”

Bugnini wanted to pursue a “streamlining of the liturgical apparatus and a more realistic adaptation to the concrete needs of the clergy and faithful in the changing conditions of our day.”

Again, the words Bugnini used to describe the liturgy - 'superstructures', 'apparatus', 'changing conditions of our day' - are revealing of a certain mindset. It was a mindset that Bugnini would use his significant organizing skills to put into effect as secretary of the Consilium.

The Second Vatican Council

After Pope St. John XXIII announced his intent to convoke the Second Vatican Council, Bugnini was appointed to serve as secretary to the preparatory commission for the liturgy for the Council. Perhaps the most significant of the preparatory commission’s suggestions was that

“the “‘structure’ of the ‘so-called-Mass of Saint Pius V’ had to be ‘reformed’ in such a way that additions be suppressed and that other elements improved or embellished,” and that “elements genuine, fundamental, and suited to our times should be cultivated.”

With the inception of the Second Vatican Council, Bugnini suffered the first of two significant demotions in his ecclesiastical career. Bugnini, with good reason, had expected to be named the secretary of the Council’s Commission on the Liturgy. Instead, that position went to another priest. Bugnini would serve simply as a peritus, an expert. But Bugnini would not be out of favor for long.

Sacrosanctum Concilium was the first constitution adopted by the Council Fathers on November 22, 1963. In early 1964, the Consilium was established with Bugnini as its secretary.

It is with the inception of the Consilium that Chiron’s book takes on the pace of a gripping novel.

A key to understanding the Consilium was its autonomy from the Roman Curia. It could function in ways that normal curial congregations could not. And given that Bugnini had already established a strong relationship with Pope Paul VI and that Bugnini was the day-to-day administrator of the Consilium, he had considerable power. As Chiron writes, Bugnini “was truly the architect of the reforms that were about to begin.”

And the reforms began almost right away and in a piecemeal fashion. Chiron documents something we too often forget.

While the Novus Ordo did not go into effect until Advent 1969, significant liturgical experimentation and changes were being undertaken in the six years between the promulgation of Sacrosanctum Concilium and the Novus Ordo’s implementation. The Holy See issued several documents, produced in large part by the Consilium that revised portions of the Mass and allowed for different options prior to the implementation of the Novus Ordo. [Since I lived in the Philippines at that time, none of these interim changes were reflected or even hinted at in the practices of the Church in the Philippines.]

For instance,

Inter Oecumenici, issued in 1964, called for

- the recitation of the Our Father in the vernacular by priest and congregation together,

- introduced the prayer of the faithful,

- suppressed the Last Gospel and the Leonine Prayers, among other things, and

- introduced the possibility of Mass facing the people. As Chiron writes,

this concession was soon to become the norm” with Paul VI “himself giving the example.”

In 1967, the Holy See issued another instruction on the liturgy,

Tres Abhinc Annos. Chiron states that it introduced “significant modifications to the celebration of Mass” including

- reducing the number of the priest’s gestures — kissing the altar, signs of the cross, and genuflections, and

- “completing the introduction of the vernacular into the Mass by allowing the Canon to be said aloud and in the vernacular.”

The Consilium would continue to revise the new rite in the years to come, soliciting feedback from cardinals and bishops attending the 1967 meeting of the Synod of Bishops. The Mass was also tested in front of the synod fathers, though the reaction was decidedly mixed.

After further revisions, in January 1968, over the course of three days, the Consilium celebrated three versions of the new Mass in front of the Pope, using different Eucharistic prayers and different “modes of celebration.” This new version of the Mass added the “Sign of Peace,” which had not been used at the demonstration of the Mass to the Synod of Bishops.

What is striking about Chiron’s description of these experimental Masses is

the way in which the new Mass was essentially Beta-tested. Reading Chiron’s description, one cannot help but think of

engineers in a design studio designing a product, tweaking it, and then testing it out on a pilot group before introducing the product to market.

This new Mass was not the result of the slow organic growth of certain practices and the paring back of others. Rather, it was the product of experts and technicians working it out abstractly in a “laboratory.”

“Even before the final Novus Ordo was promulgated,

- the Holy See permitted the use of eight new prefaces and the three new Eucharistic Prayers in addition to the Roman Canon.

- The finalized Novus Ordo “synthesized and made official changes that had already been taking place.” These included the following: - “a more communal penitential part of the Mass;

- more numerous and diverse Sunday readings spread out over a three-year cycle;

- a restored ‘universal prayer’;

- new Prefaces; a changed Offertory;

- three new Eucharistic Prayers . . . ;

- modified words of consecration, identical in all four Eucharistic Prayers;

- the Pater noster said by the whole congregation, [and]

- suppressed many genuflections, signs of the cross, and bows.”

In short, the Mass we know today.

Bugnini’s final years

In Chiron’s final two chapters, he discusses Bugnini’s fall from grace and eventual service as Apostolic Nuncio to Iran. Bugnini seems to have served ably and nobly as the nuncio. And, as relations between the Vatican and Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre and his Society of Saint Pius X worsened, Archbishop Bugnini urged restraint and mercy. He even “suggested that the celebration of the traditional Mass might be authorized,” subject to certain conditions. The Vatican rejected this advice. On a visit to Rome for medical care in 1982, Bugnini died of an embolism. He was buried with the epitaph: “

Liturgiae amator et cultor”— Lover and Supporter or Cultivator of the Liturgy.

Chiron’s book provides a helpful vehicle by which to assess, at least partially, Bugnini and his efforts at liturgical reform. If one were to base this assessment simply on output and results,

Archbishop Bugnini must be judged a resounding success.

- In the space of six years he took the general directives of the Second Vatican Council and engineered a new missal for the Latin Rite.

- The Mass, which had been celebrated for centuries in Latin, was now celebrated, almost exclusively, in the vernacular.

Within a half-decade, Mass went from being celebrated ad orientem in both the East and West, to being almost exclusively celebrated versus populum in the Latin Rite.

- The reforms directed and overseen by Bugnini have become deeply embedded in the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church.

And, yet, reading this wonderful book in light of the 50 years since the Novus Ordo’s implementation, Bugnini’s legacy is decidedly more mixed, even negative. Bugnini and the other members and consultors who manned the Consilium were undoubtedly experts in the practice and history of the liturgy.

Bugnini's legacy, however, raises the very important question whether they were, as Paul VI famously described the Church, “experts on humanity.”

- The buzzwords of their articles, talks, and titles of their books betray their biases and presuppositions and suggest that they were not experts on humanity.

- For instance, Dom Botte’s book describing his inside view of the liturgical reform is titled

From Silence to Participation. Bugnini described the transformation of the “inert and mute assembly” into true participants. Such descriptions are a common theme.

- The liturgical reformers failed to see how silence could be a form of participation, indeed perhaps a deeper participation than the recitation of banal translations.

- The reformers also seemed unable to credit ordinary lay people with the ability to learn and penetrate the mysteries of the Mass as it was already being celebrated. If these people could not “understand” the words, they could not truly worship.

- Bugnini had to paraphrase the Mass to make it “accessible.” This both assumes that one can really comprehend phrases such as, “Take this, all of you, and eat of it, for this is my body,” and obscures the manner in which mystery and comprehension coincide and overlap. As we begin to grow in knowledge, we realize that God’s mystery is even greater than we ever imagined.

“The reformers’ zeal for relevance and for a liturgy fit for contemporary man was and is a fool’s errand. As soon as one “updates” a liturgy, it is suddenly out-of-date. The new new man succeeds the new man. And so on and so forth. Nor does this chasing after relevance take into account man’s eternal and universal thirst for transcendence.

Finally, Bugnini and his fellow reformers put a premium on rational comprehension and stark simplicity. But this was done at the expense of basic human anthropology and a proper understanding of God.

- We are not simply spirits, but embodied souls who need to touch, to feel, to taste, to see.

- When we no longer kneel, genuflect, kiss, adore, we often cease to believe.

- We may now “understand” the words of the liturgy but at the expense that we do not actually believe them.

- Further, God is superabundant. His language is superabundance. He expresses Himself in ways that seem excessive, even superfluous. Why should our worship of Him be any different?

Chiron’s book is a great gift to the Church. While we cannot change the past, Chiron gives us the ability to see it clearly, to assess it with honesty, and to ask the deep questions that will help us avoid making missteps in the future. Bugnini was clearly well-intentioned.

He loved the liturgy. [His way, however. Not that which had organically developed over centuries, the liturgy that nurtured all of the Church's Fathers and saints. It's like saying 'Bergoglio loves the Church' - yeah, but his church, not the Church Christ instituted.] But so many of his actions undermined rather than cultivated the liturgy he loved. May we avoid repeating his mistakes.

Still on the subject of liturgy - would Bugnini have approved of the absurd but open license with which bishops and priests have since abused 'his' liturgy?

The Eucharist as a snack

Translated from

January 29, 2019

The case I am concerned with here would have been perfect for my feature ‘Right men in the right places’. but I have chosen to treat it on its own because it demonstrates very well the point we have reached in liturgical degradation, an expression of theological and spiritual degradation before which one is left without words.

I refer to the Mass celebrated in Innsbruck by Austrian Bishop Hermann Glettler on January 29, during which the young people who took part gave communion to each other, and all of it seen live on ZDF television. Here is how the webite messainlatino,it. recounts it:

At the Offertory, the high school students took the microphone to explain that they were ‘preparing the table”. And the video shows the communion that they subsequently gave to each other.

But the young people apparently had to ‘swallow’ the irreverent novelty proposed and allowed by their bishop. On the video one sees the displeased expressions of some of the kids who, after receiving communion from one of their colleagues, walk away rapidly while making the sign of the Cross, while others approached the improvised ‘eucharistic ministers’ with classic adolescent sniggering.

This is a shame for which the Bishop of Innsbruck is responsible before God and the Church.

We already observed earlier the ‘artistic’ strangenesses introduced by this ‘creative’ bishop’, but we never imagined that he could allow the children themselves to give communion to each other during one of his masses.

The video also shows a boy holding for the bishop a ciborium with the consecrated hosts while in the background, an instrumental group is playing ‘New Age’ music.

This is the spiritual level to which Austria has been reduced – a nation that was once resplendent in its Catholic devotion and courageous testimonials in defense of the faith.

Not afraid of being branded as neo-pelagians or hypocrites (but better than bearing the guilt for disturbing the faith of children), can we say that this schismatic way of conceiving liturgy is also dangerously dis-educative for the young and ground for ‘scandal’ to the entire ecclesial community?

What are the faithful of Innsbruck waiting for in order to address this scandal to the competent Vatican dicasteries (the Congregationf or Divine Worship and the Congregation for Bshops) in order to safeguard their own faith and above all, t protect the faith of their children and grandchildren?

I have little to add to this account, including its final question. Only a prayer for reparation.

I conclude this post with an item I had been waiting to post for several days... And here it is - a fitting counterpoint to the Bugnini story and the radical changes he engineered to create the Novus Ordo...

Should a priest introduce the old Mass

to a congregation that does not request it?

by Peter Kwasniewski

January 21, 2019

Let’s begin with the most obvious point, which nevertheless still needs to be said. As per Summorum Pontificum, if the faithful themselves request the traditional Latin Mass, the pastor must provide it for them, or at least make arrangements for another priest to provide it.

He is not allowed simply to say no. He might say “yes, but first I have to learn it” (and then the laity, already prepared, will tell him that they will cover all his expenses); or “yes, but at this difficult juncture — with the new elementary school, the prison ministry, the nursing home, and the recent death of the vicar — I won’t be able to learn it, so I will ask around and try to get a Mass started for you next month.”

And of course, the pastor will always make such responses with a smile and gratitude for the devotion of his faithful to the rich traditions of the Catholic Church.

But what about a situation where the people are basically content with what they’ve got? They are accustomed to the “Ordinary Form” and know nothing else; they are not asking for anything else. Let’s even say, for the sake of argument, that the parish is on the upper end of the Ratzingerian scale and is already putting into practice the ideals of the ROTR, [reform of the reform] such as ad orientem, use of Latin and Gregorian chant, fine sacred music, beautiful vestments, kneeling for holy communion, and the like.

- Is there anything “wanting” to such a community?

- Is there any reason for the pastor himself to introduce the usus antiquior?

Yes. There are two basic reasons to do so.

First, for the priest’s own benefit. In an article published in Catholic World Report,

“Finding What Should Never Have Been Lost: Priests and the Extraordinary Form” (one of many such articles now online), we find testimonies from priests about the effect that celebrating the usus antiquior has had on them, and why they find it so moving.

One priest says: “It has a mystical, contemplative, and mysterious quality, with its use of Latin, the gestures, the position of the altar, and the prayers, which are more ornate than we have today.”

Another priest remarks: “I was a lifelong Catholic, and I’d never experienced the Mass in that way. I didn’t imagine such a Mass existed. I was enthralled by it. When I celebrate the Mass, it has less to do with me, the priest, and is more about God.”

A third priest states: “The Tridentine Mass has changed me. I like its reverence, and it’s helped me see the Mass as a sacrifice, not just a memorial.”

Every priest I know who offers the traditional Latin Mass — and I have spoken with hundreds over the years — experiences in a powerful, almost visceral way the awesomeness of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and of the mystery of the priesthood on account of many elements in the liturgy that were unfortunately removed in the reforms of the 1960s:

- the humble approach to the altar at the beginning, which is saturated with the humility and piety that befits “being about the Father’s business”;

- the many times the priest must bow or genuflect, the many kissings of the altar and signs of blessing;

- the exquisite attention to meaningful detail in one’s posture, attitude, and disposition;

- the profound prayers of the Offertory;

- the immersion into silence at the Canon, so piercingly focused on the mystery by which the immolation of Christ is renewed in our midst;

- the care that surrounds every aspect of the handling of the Body and Blood of the Lord, from canonical digits to thoroughgoing ablutions;

- the Placeat tibi and Last Gospel, which bring home the magnitude of what has taken place: nothing less than the redemptive Incarnation continuing in our midst.

How could this not hugely benefit a priest in his interior life, and lead him further along the path of his vocation and his sanctification?

The second reason for a priest to make the usus antiquior available even when his congregation has not requested it is for the spiritual benefit of the congregation itself.

One of the priests interviewed in the aforementioned article points out: “Ninety percent of Catholics today have had no experience of the Church before Vatican II. They don’t know about its traditional art, architecture, or liturgy.”

As Joseph Ratzinger lamented more than once, there was a rupture if not in theory, then certainly in fact. Catholics were separated from the traditions of the Church; indeed, adhering to traditions came to be seen as a sort of infidelity to Vatican II and to the new spirit it ushered in, which was supposed to newly engage modernity and bear the harvest of a new evangelization.

- This does not seem to have happened, or not with the fullness that had been desired and promised.

- If anything, it tended to encourage skepticism towards anything preconciliar and a promethean temptation to refashion the Church according to the latest fads and theories.

Although the worst of the “silly season” may be over (at least in most places), the People of God still suffer from the effects of this widespread deracination.

What better way to root them again in the two millennia of Catholicism than by enriching them with the form of worship that nurtured the great saints of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Baroque, and the entire Tridentine period that stretched over four and a half centuries?

In the memorable words of Pope Benedict XVI’s letter to bishops, Con grande fiducia:

“It behooves all of us to preserve the riches which have developed in the Church’s faith and prayer, and to give them their proper place.”

This can only be a “win” for the faithful in the parish, stretching them in good ways.

- It will develop new habits of meditative and contemplative prayer; - it will strongly confirm the dogma that the Mass is a true and proper sacrifice;

- it will intensify their adoration of the Most Holy Eucharist and their veneration of the ministerial priesthood (which is not a species of clericalism);

- it will open their minds to a wider world of Catholic culture and theology; and

- last but not least, it will support the effort to celebrate the Novus Ordo in a more traditional manner by showing where the ROTR paradigm came from in the first place — in other words, why we do certain things this way rather than that way.

We may conclude this part of our exposition with the striking words of the late Darío Cardinal Castrillón Hoyos during his tenure as the president of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei:

Let me say this plainly: the Holy Father wants the ancient use of the Mass to become a normal occurrence in the liturgical life of the Church so that all of Christ’s faithful – young and old – can become familiar with the older rites and draw from their tangible beauty and transcendence. The Holy Father wants this for pastoral reasons as well as for theological ones. (London, 14 June 2008)

When asked at a press conference on the same day “Would the Pope like to see many ordinary parishes making provision for the Gregorian Rite?,” His Eminence replied:

All the parishes. Not many — all the parishes, because this is a gift of God. He offers these riches, and it is very important for new generations to know the past of the Church. This kind of worship is so noble, so beautiful — the deepest theological way to express our faith. The worship, the music, the architecture, the painting, make up a whole that is a treasure. The Holy Father is willing to offer to all people this possibility, not only for the few groups who demand it, but so that everybody knows this way of celebrating the Eucharist in the Catholic Church.

One question I am often asked by laity and clergy is: “How should the Extraordinary Form be introduced where it has not yet existed?” I think what they mean is largely practical: when, how often, and with what preparation or accompaniments.

My advice has always been to do it gradually: to start quietly (I mean, without fanfare) by scheduling a monthly Mass; then, once this Mass is known to be celebrated and there is some congregation for it, to offer catechesis to the rest of the parish in homilies, and a kindly invitation. After this has gone over well and has become an accepted fact, the frequency can be increased to once a fortnight or once a week.

At this point, the priest reaches a crossroads: if he judges that the community will respond favorably and his head will not be handed to him on a platter at the chancery, he could celebrate the usus antiquior several times a week. I have seen regular parish schedules where it is offered as the daily Mass on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, or where there is a Sunday Mass and a weekday Mass.

To get even more particular, it has often worked well to introduce a traditional Latin Mass on Saturday morning, because this is a “low traffic” time of the week, and least likely to ruffle feathers. In some parishes there isn’t even a normal Saturday morning Mass, so nothing has to be swapped out. Another possibility is First Fridays and/or First Saturdays, because these are well-loved but traditional devotions, and the Latin Mass can be viewed as their natural complement: it sounds like a special thing being done for a special devotion. Another pastor I know introduced a monthly evening Mass just for men and boys, as part of a program of adoration, rosary, Mass, and fellowship; he will soon introduce a monthly evening Mass just for women and girls.

Introducing the usus antiquior on Sundays or Holy Days is at once the most important step and the most difficult.

- It is important to do so eventually, because only in this way can the treasure of the old liturgy reach the largest number of faithful.

- It is obviously difficult because of the need (in some places) for many Masses offered by a single priest, as well as by the challenge of an already-existing schedule that parishioners are loath to see modified.

Still, even here there can be a way forward. For example, if there is already a quiet early morning Mass, one might convert this into a quiet Low Mass, being careful to repeat the readings from the pulpit in the vernacular before the homily.

If there is a “contemporary youth Mass,” why not try the wild and crazy New Evangelization experiment of substituting a Gregorian Missa cantata for it instead? A lot of young Catholics are bored or turned off by the pseudo-pop music and the implicit dumbing-down that liturgical planners assume to be necessary for the smartphone generation. As always, some youths might stop coming, but others would find in it a radically new experience that appeals to them in mysterious ways. New people would come — and bring more people. It could end up being quite successful.

In all of this, I am painfully aware of the reality on the ground.

- There are many priests who feel that their hands are tied on account of the hostility, on the part of the bishop, the chancery, the presbytery, or the parish, towards anything traditional.

- This is a deplorable aspect of our decadent situation, but it is not a dead end.

- In such cases, a priest still profits from learning the usus antiquior, as he can offer it privately once a week on his day off. -

This will be to his own spiritual benefit for all the reasons already given, and, by connecting him to a wealth of tradition, influence for the better his understanding of what liturgy is and how it should be celebrated in any rite or form.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 01/02/2019 05:48]