The following review of Ross Douthat's new book seems typical of those 'normalists' who have bent over backwards any which way to give Bergoglio the benefit

The following review of Ross Douthat's new book seems typical of those 'normalists' who have bent over backwards any which way to give Bergoglio the benefit

of the doubt in terms of his motivation for what he has been saying and doing as pope, although they acknowledge the obvious failings of his pontificate thus far.

At least, Mr White's title 'The pope's mess' gets it right!

The pope's mess

Five years into his papacy,

assessing Bergoglio'srecord

by STEPHEN P. WHITE

THE WEEKLY STANDARD

March 23, 2018

Pope Francis’s pontificate did not begin with doctrinal controversy. It began with the appearance of an amiable Argentine on the balcony of St. Peter’s and endearing stories about a pope who rides the bus and pays his own hotel bills.

His papacy seemed to present an opportunity to draw together two competing visions of Catholicism’s proper disposition toward the contemporary world. At the risk of oversimplifying, the first vision wants the church to be more open and democratic. The other has more traditional and hierarchical emphases.

Each, at its best, represents a legitimate, orthodox vision of Catholicism. Each, at its worst, flirts with dissent, rupture, and even schism. Like brothers who sometimes quarrel, each tends to be wary of the other. As inadequate as the political terms “liberal” and “conservative” are to this purpose, they can work as shorthand: If Francis’s immediate predecessors were more or less conservative, the newly elected pope appeared to be more or less a liberal, but

well within the bounds of Catholic orthodoxy.

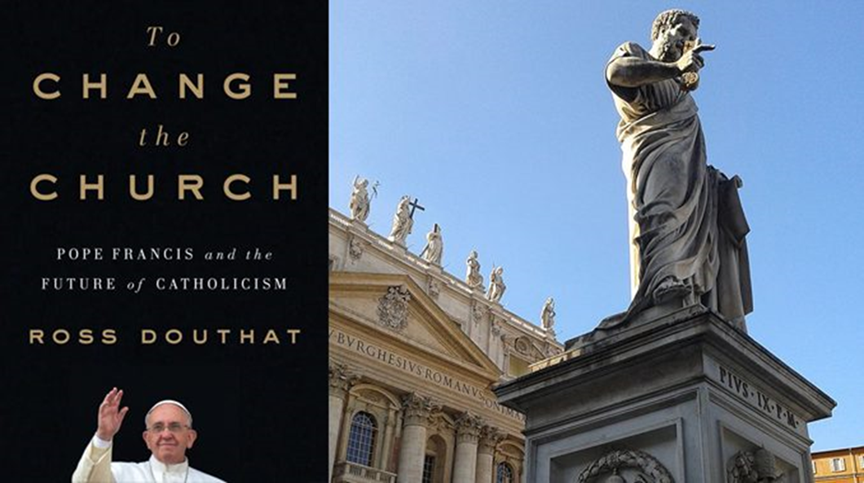

Five years later, these longstanding divisions have not been resolved; in fact, they have become so aggravated that the worst version of each side is often on display. Ross Douthat, in his new book,

To Change the Church, looks at Francis’s pontificate, examining both the missed opportunities and the ongoing search for a new, stable synthesis.

In even admitting the promise of this pontificate, Douthat is showing more good will and sense than many of the pope’s critics do. And Douthat is certainly himself a critic, if a thoughtful and pious one. Regular readers of his New York Times column will not be surprised to learn that Douthat has written the most balanced and least polemical of the recent critiques of this pontificate. Pope Francis tends to elicit strong reactions from commentators, and Douthat offers if not a dispassionate assessment then at least one that takes seriously the limits of assessing the legacy of any pontificate after just five years.

[But the assessment in this case is not a question of time - rather, of how much damage has been wrought by one man in so short a time!]

To help his readers understand this papacy’s initial promise and the controversies it has engendered, Douthat begins by walking them through the last few decades of Catholic history. In the years following the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), all manner of weirdness (and worse) wafted into the Church — some of it revealing how fragile and vulnerable the Church had already become by the time the council began.

A manic spirit of experimentation and worldliness spread through the Church, eventually exhausting itself in jaded cynicism. Seminaries emptied; religious orders imploded. Catholic catechesis and sacramental discipline entered a long slump. This was when the sexual abuse of minors by Catholic clergy was at its diabolical peak, although most of it wouldn’t come to light for many years.

In 1978, Pope John Paul II was elected. He set about restoring order after a decade of dissolution. Like a trauma doctor presented with a critical case, the young pope set about stabilizing the patient. Bleeding was stanched, bones were set, splints and casts and braces were applied. It took decades, but by the time John Paul’s successor, Pope Benedict XVI, abdicated in 2013, the patient appeared stable. There were crises, to be sure — the long-overdue reckoning on the sexual-abuse problem, notably — but the Church had survived the worst of its internal injuries.

Sooner or later, splints and casts and braces have to come off. Limbs that haven’t borne weight need strengthening and exercise. Joints that have grown stiff need to become flexible and limber again. If one is to become healthy, stability must sooner or later give way to a new stage of vulnerability. But if one proceeds too quickly and incautiously, old wounds can be reopened.

Enter Pope Francis. From the beginning, it was clear that his style was earthier, less formal, than that of his predecessors, especially the professorial Pope Benedict.

That’s part of Francis’s charm. [Yeah, right. Which was never apparent all those years he was the 'funeral-faced' Archbishop of Buenos Aires, as his own appointed successor to that office described him. That alone ought to have signaled to the media the phoniness of the public "Look-at-me-I-am-not-like-any-other pope" poses taken by Bergoglio once he became pope. On the other hand, he obviously revels in the supreme 'stature' and immense popularity he has as pope, so his conversion from pickle-faced martinet to jovial bonhomme Bergoglio may be genuine in that respect.]

If the Argentine pope’s politics have more of a Peronist flavor, it’s also true that

he is hardly the first bishop of Rome to warn against consumerism and the exploitation of creation or to remind the affluent of their obligations to the poor, the sick, the migrants. [Correct, but that is not how the media has portrayed him - in their portrayal of him, it is as if no pope before him had ever thought about the poor and the needy! The difference, of course, being that previous popes were more concerned about the spiritual needs of their flock, even if by the 20th century, the Church had become the single most committed 'social and charitable' organization around the world, which was active the year round in the daily lives of the people she helped, and not just during major emergencies.]

As Douthat points out, such remarks mostly seemed to threaten “a particularly American marriage of conservative Catholicism and free market ideology, which given the state of conservative politics in America perhaps deserved a period of papal challenge and self-critique". A pope with a moderately leftist view of the world might not be such a bad thing after 35 years of relative conservatism. As the Italians say, “A fat pope follows a thin one.”

[And in what way would a pope's leftist political and economic views be good at all for the Church? Popes are not supposed to make secular concerns override their spiritual obligations to their flock, and not one of the popes before Bergoglio since the 19th century has ever done what Bergoglio has been doing. If John Paul II is credited along with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher for having brought about the collapse of Communism in Europe a mere seven decades after the Russian Revolution, it is not because he went out of his way to play a role in it - it was because he himself, unlike Reagan and Thatcher, had personally endured the scourge of communism for decades and seen what it had done to his country. Therefore he used his moral authority as pope - and any material resources he could solicit - to strengthen the democratic opposition to communism in Poland primarily via the Solidarity movement. It was above all the Godlessness of communism that he resisted - a factor Bergoglio appears to completely ignore in his kowtowing to Beijing and his patronage of Godless Communist/socialist leaders like Raul Castro, Evo Morales and Nicolas Maduro.]

Beneath all this,

Pope Francis still clearly shared his predecessors’ conviction that the church exists to preach the gospel to a world desperately in need of it. [EXCUSE ME, NO, NOT AT ALL! How many times has he said he is not interested in converting anyone to Catholicism, or Christianity for that matter; that everyone, whatever faith he may profess or not profess, is just right where he should be; that what matters most is 'dialog' with one another - thus virtually killing the idea of mission in the Church! In one of his least subtle (but hardly noticed) critiques of this pontificate, Benedict XVI in 2015 denounced the idea that dialog could ever be a substitute for mission!]

In other words, he knew that for the Church to be what she must be, she couldn’t spend all her efforts looking inward. [But who, other than Bergoglio, ever said the Church was only looking inwards, gazing at her navel, as it were, and in Bergoglio's censorious term, 'self-referential'?] Chronic dysfunction and corruption in the Vatican curia, new waves of sex-abuse scandals in Europe, and the long war of attrition between the church and secular culture —especially on issues like same-sex marriage and abortion —

had left the Catholic church in a decidedly defensive posture. An overly defensive church can easily forget that it has a mission. [What claptrap! The best defense is doing right, which is what Benedict XVI's Pontificate sought to do in every way, and doing right means not abandoning the essentials of the Church, not just her articles of faith, but also everything worthy in her bimillennial tradition and magisterium, in order to 'accommodate the world', as Bergoglio is doing.]

And so Pope Francis’s early priorities reflected a refreshing reemphasis on the church’s primary mission. He wanted a church that is less self-referential, less closed in on itself; he wanted a church that leads with tenderness rather than judgment; he preferred a church that is “bruised, hurting, and dirty” from having been in the streets over a church that is “unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security”; he wanted shepherds “who smell like their sheep”; he said he wanted a church “that is poor and for the poor.” He envisioned the church as a field hospital, where those shattered by a “throwaway culture” can receive mercy’s balm. [YECCHHH! that faithful iteration of Bergoglio's worst (because ultimately meaningless) cliches makes me gag. They are false and fallacious to begin with. One could write a whole essay just tearing down the erroneous and even outrageous premises found in those statements, which everyone parrots without grasping the obvious fallacies they proclaim, much less denouncing them for being erroneous and outrageous!] In all of this, Pope Francis sought to move the church toward the very same goal his predecessors had desired: a “new evangelization” for the world and a “new springtime” for Catholicism. [How can there be 'new evangelization' if he thinks no one needs to be evangelized because "everyone is just right where he is", even and especially the Muslims (not that he would even think of asking any Muslim to convert! - because that will surely earn him instant 'fatwas' from all the imams and mullahs of the world)? And his idea of a 'new springtime' for the Church was to spring his own church of Bergoglio, built to his image and likeness, on the unsuspecting Catholics of the world, who certainly never expected -

nor realize just yet - that they have a genuinely anti-Catholic pope!...Isn't it amazing how much revisionist mythmaking is already at work - even among non-Bergoglidolators - when the events referred to are not even five years old yet.]

The decisive shift in Francis’s pontificate toward doctrinal brinksmanship arose, it seems, not out of deep ideological commitment to theological liberalism, but from his genuine fervor for bringing mercy and compassion to the fore. [Possibly the most disingenuous way to put an unmerited gloss on Bergoglio's 'doctrinal brinksmanship'! White is completely a-critical of the fact that Bergoglian mercy is totally divorced from justice and genuine charity towards those to whom one feigns mercy!]

On the question of communion for the divorced and remarried, the pope looked to aging German theologians whose pastoral conclusions —if not the Hegelian theology used to reach those conclusions —enthralled him, ultimately convincing him to push the doctrinal envelope in ways very few of his predecessors ever have and in ways his most immediate predecessors had rejected outright. In doing so, Douthat writes, the pope threw away a golden opportunity

by wedding his economic populism instead to . . . the moral theology of the 1970s, making enemies of conservatives (African, American, and more) who might have been open to his social gospel, treating economic moralism not as a complement to personal moralism but as a substitute . . . and driving the church not toward synthesis but toward crisis.

[White has also failed to acknowledge completely the absolute deliberateness with which Bergoglio has been pursuing his abracadabra legerdemain in mutating the Church he was elected to lead into his personal fiefdom which is more properly called the church of Bergoglio.]

The “marriage problem,” as Douthat calls it, was the focus of two synods (large meetings of bishops) that convened in Rome in 2014 and 2015. The synods were supposed to highlight the more collegial, less hierarchical style of governance Pope Francis wished to exemplify, but they instead became moments of intense controversy. Douthat covers the machinations and politicking at these synods in great detail, but what matters is that

the pope and his handpicked managers went to great lengths to achieve the outcome they preferred: some version of the German proposal to allow communion for the divorced and remarried. In the end, they were frustrated, but the fight exposed and solidified the deep divisions between those opposed to such changes and those in favor. [They may have been frustrated because they did not get the votes they wanted from the two synods, but that did not stop Bergoglio from legislating his own will anyway in Amoris laetitia - simply trampling on any vestige of collegiality or synodality by insisting on what he wanted from he start to begin with. I certainly hope Douthat did not present this the way White appears to synthesize him, because it is simply wrong, and in stark opposition to well-documented facts.]

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of this disagreement for Francis’s papacy and for the future of the church: Supporters of opening a new path to communion for the divorced and remarried claimed the matter was simply a question of “updating” and “reforming” church discipline in certain limited circumstances; opponents insisted that the proposed changes would create a rupture with the settled doctrine of the church.

But the changes Francis and his allies hoped to institute stretched the limits of what is doctrinally possible, even for a pope. The question of communion for the divorced and remarried has profound implications for nearly every aspect of theology. [Well, that's a sensible admission from White, for once!]

Standing in the way of the permissive, pastoral approach Pope Francis seemed to favor are the explicit teachings of numerous popes and ecumenical councils, two millennia of Catholic Christianity, and, above all, the unambiguous words of Jesus himself: “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery.” [Yet still, White would give Bergoglio the benefit of the doubt!]

When two baptized Catholics marry, nothing except death, not even the pope himself, can dissolve that union.

[Not entirely true, because the Church did allow for marriage annulments when merited. Of course, Bergoglio since then has relaxed and 'simplified' all the rules for the declaration of marriage annulment to the point that the Bergoglio annulment process is tantamount to a quickie Catholic divorce.] And so long as you’re married to one person, you can’t go starting a new marriage with someone else. Adultery, like any other serious sin, precludes a Catholic from receiving communion until that sin is confessed and absolved.

The reformers insisted their proposals would not change any of that. But they could not explain how their plan — to permit people who, as far as the church was concerned, were not married to receive communion while still living together as husband and wife — did not contradict in practice what the Church clearly taught in principle.

Something had to give: Christ’s own words on the indissolubility of marriage and the nature of adultery; or St. Paul’s teaching about the need to receive the Eucharist worthily, and thus not in a state of serious sin; or the Church’s perennial teaching that real repentance is required to receive absolution in confession; or her infallible teaching that the commandments are never impossible to keep, no matter how trying the circumstances. ['Something had to give'??? But why? The teaching of Jesus - and St. Paul's masterly enunciations of it - cannot suddenly be 'not true' in certain cases! I am still waiting for White to denounce the moral relativism at the rotten core of this pontificate.]

In early 2016, Pope Francis published the longest papal document in history, an apostolic exhortation called Amoris Laetitia

[an extreme at of self-indulgence I am tempted to call mental masturbation] which in Douthat’s words

“yearned in the direction of changing the church’s rules for communion . . . its logic suggested that such a change was reasonable and desirable. Yet [Pope Francis] never said so directly.” [For obvious reasons! He was not about to provide his critics with documentary evidence of material heresy. The moral cowardice of this man is beyond description. But of course, he would justify it on the practical grounds of self-preservation. He would be foolish to convict himself by saying clearly what he is saying indirectly in thousands of other ways!]

In the document, the most fraught and contentious question of the synods — the source of so much friction, drama, and division — was reduced to a single, studiously ambiguous footnote. When it came to the church’s pastoral care for those in irregular marital situations, the pope noted, “In certain cases, this can include the help of the sacraments.” [COWARDICE WRIT LARGE IN A FOOTNOTE FOR ALL THE WORLD TO SEE!]

Which sacraments? Under which conditions? Was this a restatement of prior teaching or a reversal? The document didn’t say. Pope Francis apparently settled on a do-what-I-mean-not-what-I-say approach. He may have hoped to leave the matter ambiguous enough to prevent a doctrinal crisis while still allowing room for more permissive pastoral practices.

[Of course, he knew it would lead to division! What does he care as long as he gets his way, i.e., overturn Church teaching, never mind if that teaching goes back directly to Christ himself! His motto is 'Hagan lio! Make a mess!" and he is simply practising what he preaches.]

And that approach might have succeeded [How, in heaven's name? As if we have not had 50 years to live with the unfortunate effects of deliberate ambiguities in the Vatican -II documents!], if not for the fact that different bishops around the world began interpreting the ambiguous footnote in radically different ways.

[Isn't that the inevitable outcome of any ambiguity, as surely Bergoglio knew? Everyone then feels free to interpret the ambiguity as he wishes!] Even those who praised the new teaching couldn’t agree on just what was being taught. The sacramental discipline and moral teaching of the Catholic church began to divide along national and diocesan boundaries almost immediately.

In Poland, for example, the bishops reiterated existing teaching that the divorced and remarried could not receive communion. Other bishops, hoping to use the wiggle room created by Amoris Laetitia to push for far more radical changes, got straight to work. In Germany, where declining to pay the church tax gets you excommunicated and where pews are empty but coffers are overflowing, the bishops have pushed for opening communion to certain non-Catholics and have floated the idea of blessing same-sex partnerships.

In light of the more radical interpretations of the pope’s teaching, more traditionalist prelates have made official requests for the pope to clarify just what it is supposed to mean. These requests have been ostentatiously ignored, and the inquirers treated like ecclesiastical pariahs.

As the gaps in teaching and practice from diocese to diocese have widened, it has become clear that something more than the pope’s wink-wink-nudge-nudge approach is required. [Think about it! How can White, or any other Catholic, refer to Bergoglio's wink-wink-nudge-nudge tactic as if it were a mere peccadillo, when for a pope, especially, it represents the most bare-faced dishonesty!]

The pope retroactively elevated to magisterial status a private letter he had written to the bishops of Buenos Aires praising them for their guidelines for interpreting and implementing Amoris Laetitia and claiming “no other interpretations are possible.” [And was that not a blatant display of mala fides by Bergoglio - yet still vague enough for his action not to be interpreted as outright heresy, or, as I prefer to think of it, apostasy, which is worse than heresy?] This includes — presumably — the Argentine bishops’ claim that in certain circumstances, it is “not feasible” to not commit adultery and that in such cases folks might be able to receive communion. The pope could not be less interested in explaining how this interpretation squares with the Council of Trent’s teaching that following the commandments is never impossible.

So far, the debates over Amoris Laetitia have involved mostly bishops, priests, and theologians; Pope Francis has left the defense of his ambiguous magisterium to a coterie of advisers and subordinates who enjoy the deference afforded them by their proximity to him. Meanwhile, the acrimony of the marriage debate seems to have surprised the pope and pushed him away from consensus-seeking and more solidly toward the reform-minded prelates who supported him through the synods and who are now eager to cement Francis’s legacy,

lest it all be washed away in the next conclave. [In fact, however, bad legacies are always the most difficult to overcome and correct, and unfortunately, the evil Bergoglio has been working will live on long after he passes away.]

As Douthat notes, looking back at the last several years,

“Francis’s apologists knew very well that they weren’t just defending simple pastoral flexibility against the rigor of conservatives. Flexibility they surely wanted, but there was also clearly a more revolutionary vision implied and waiting underneath.” [There are revolutions and revolutions, and obviously, some can be very bad indeed! Just think of the 1968 overnight Cultural Revolution and how, in the Church, it synergized the 'spirit of Vatican II' that had already prefigured the 'spirit of 1968". Yet the way White, and Douthat, use the word, one would think that 'revolutionary' is always necessarily positive.] How far they will be able to press that revolution, and whether Pope Francis will eventually try to slow the revolution

being waged in his name, remain open questions.

There is little sign that Catholics in the pews on Sunday — or not in the pews, as the case may be — are much concerned with the debates over Amoris Laetitia.

[They couldn't care less about the debate! What matters to them is what their bishops and priests lay down to them in the form "The pope says..." Which they will accept as the 'new teaching' of the Church, and few will ever question, the way hardly anyone protested in 1970 when the pope said - Paul VI at the time - that overnight, the Church was dumping the traditional Mass into the dustbin of history, and here is your new Protestantized Mass!]

But the stakes are too high and the interpretations of its teachings too diverse for the current situation to remain stable for long.

The Church can tolerate, and for a long time, a great deal of diversity in pastoral practice. But diversity in principle? Deep disagreement about the moral law, the sacraments, and the limits of doctrine itself? Divisions on issues so fundamental have a way of leading to deep and lasting damage to the unity and credibility of the church—to schism and worse. [Another sensible paragraph from Mr. White!]

On this point, Douthat takes a pessimistic view:

The Church has broken in the past, not once but many times, over tensions and issues that did not cut as deeply as the questions that undergird today’s Catholic debates. Other communities have divided very recently over precisely the issues that the pope has pressed to the front of Catholic debates. And for good reason: Because these issues, while superficially “just” about sexuality or church discipline, actually cut very deep — to the very bones of Christianity, the very words of Jesus Christ.

[Does Douthat come out in the book to openly censure Begoglio for falsifying the Word of God with his determined omissions and false exegesis of Christ's words in the Gospel? I cannot understand why there is little outrage at - and even less acknowledgment of - Bergoglio's habitual tampering with the Word of God. What could be more hubristic and Satanic than that???]

Toward the end of his book, Douthat turns to history and attempts some synthesizing of his own, trying to find some precedent for or analogue to the season of division in which the church finds itself. He focuses on two past controversies — between Athanasians and Arians in the 7th century, and between Jansenists and Jesuits in the 17th — as templates for thinking about how the current crisis might resolve itself in the long term. Applying the lessons of these episodes, Douthat guides the reader through various permutations, balancing one interpretive narrative with another and offering likely, or at least possible, scenarios.

To his credit, Douthat is willing to entertain the idea that he is simply wrong and that others — Pope Francis and his advisers — are right. The Spirit, after all, blows where it will. And for all the clarity of the pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI,

they didn’t stem the rising tide of secularism or restore the confidence and vitality of the Church in the West. [They were fighting a battle already lost before their time, against the overwhelming social and political reality of a European Union so hostile to Christianity that it would not even acknowledge Christianity in the Preamble to its Constitution. Which should not neutralize or ignore the missionary growth of the Church in Africa all of these years - in numbers triple or quadruple the population of Europe - against social and political odds of a different kind than Europe poses, but strong odds nonetheless.] Doctrinal clarity may be necessary to the Church’s mission, but it’s hardly sufficient. [It certainly does not help any mission to have no clarity in stating what it is. Or if the pope has abandoned the primacy of the Church's spiritual mission in favor of his agenda as the now de-facto leader of the global left. Bergoglio is certainly clear enough about his intentions when he spells out the agenda for his pontificate as in Evangelii gaudium. That's when he is speaking of himself and for himself. In the same way that he is pretty clear when he is the prime endorser of Islam on the globe, and of indiscriminate mass migration. But you can't expect him to have doctrinal clarity about doctrines he wishes to do away with or change completely, because he cannot afford to self-incriminate himself with heresy or apostasy! He needs the papacy to be able to achieve his agenda completely - without the papacy, he would just be another tinpot evangelist. Luther must be writhing in hell in throes of envy over the fact that he was not pope like Bergoglio back in 1517!]

Douthat shows more confidence in his evaluation that while it may not play out in any of the ways he imagines, the crisis precipitated by the recent synods and Amoris Laetitia is not going away anytime soon. Too much is at stake.

[Not only that, but the practical reality that it is infinitely harder to get rid of an error and its effects once it has been institutionalized. As Bergoglio is laboring hard to institutionalize his errors.]

In the meantime, Pope Francis’s hopes for

a genuinely outward-looking church, a church less turned in on itself, [Dear Lord!, how can any sensible man repeat those Bergoglian cliches as if they meant anything at all???] have likely diminished:

The theological crisis that [Pope Francis] set in motion has made Catholicism more self-referential, more inward-facing, more defined by its abstruse internal controversies and theological civil wars. The early images of the Francis era were missionary images, an iconography of faith-infused outreach. [That's baloney! It was all and only ever the stuff of media narrative, none of it real at all! What faith was his 'outreach' infused with, when, from the very beginning, he made it his calling card to say, "I am not interested in converting anyone to Catholicism. Everything is fine just where they are. God accepts them as they are, where they are"?] The later images have been images of division — warring clerics, a balked and angry pope, a church divided by regions and nationalities, a Catholic Christianity that cannot preach confidently because it cannot decide what it believes.

It’s not really the case that Catholicism can’t decide what it believes. [But Douthat was making a hyperbolic statement. The Church, the timeless eternal Church, knows what she believes, and her ministers will preach her faith for as long as they share that faith. When they preach something else, as Bergoglio does, then you don't want them to preach confidently because they would undermine the faith inestimably, as Bergoglio does.]

In the end, the church is not merely a collection of ideas and doctrines [But whoever said that it was? It is an integral seamless garment, if you will. In which every part is just as significant as the whole!] —

about this Pope Francis is surely right [one of those Bergoglian premiseless maxims!]] — and her faith is not in men, nor even popes, but in the One who said to the first pope: “You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell will not prevail against it.” Francis is Peter

[the Peter who denied the Lord three times?], for better or worse (most likely both). The same will be true of the next pope.

If looking to history reminds us that crisis and schism are real dangers to the church, history is also a reminder, to Catholics anyway, of the old adage that the greatest proof for the truth of the Catholic church is that 2,000 years’ worth of Catholics haven’t managed to destroy it. The next conclave, the conclave that chooses Francis’s successor, whenever it comes, will be important. But it will not be, to coin a term, a Flight 93 conclave.

[If by Flight 93, White is alluding to the 9/11 airplane that crashed in Pennsylvania after a heroic attempt by some of its passengers to thwart the hijackers, I think the 2013 Conclave was itself the Flight 93 conclave that has dug for the Church what promises to be her 'grave', at least in this era.]

Douthat concludes by pointing out that, at least for now, we have a bishop of Rome who has taken to heart his own advice: “Hagan lío! . . . ‘Make a Mess!’ In that much he has succeeded.” Douthat, for his part, has succeeded in helping make at least a little sense of that mess, in ways that are both disconcerting and, taking a long enough view, reassuring. His readers will be grateful.

I am obviously too biased to think of the current state of the Church in any nuanced way at all. Simply because none of what Bergoglio is saying or doing to hasten its demolition is in any way nuanced - there is nothing nuanced about brutality in the name of change, and that is what Bergoglio displays in spades with his blatant and lurid headline-baiting exploits. And how can one continue to give him the benefit of the doubt when with every day that passes, his 'offenses' keep growing in number and degree???? No, I do not and cannot trust this man to do anything that will not be primarily self-serving for him.

BTW, I looked up Stephen White on the site of the Ethics and Policy Center in Washington (the same think tank George Weigel belongs to). White is, in fact, the coordinator since 2005 of the Tertio Millennio Seminar on the Free Society, a three week seminar on Catholic social teaching with an emphasis on the thought of St. John Paul II which takes place every summer in Krakow, Poland (and about which Weigel often writes admiringly). It therefore surprises me greatly that White fails to address Bergoglio's major problem with TRUTH! One might think that an expert on Wojtylian thought would always have Veritatis splendor in mind! But apparently not.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 28/03/2018 06:16]