I am very grateful to Fr. De Souza for marking the tenth anniversary of Spe salvi, perhaps my favorite 'short work' by Benedict XVI. After the stupendous surprise he sprung on us all by his radiant first encyclical Deus caritas est, I did not expect to be swept off my feet by an even more dazzling work which in the process of presenting the reasons for Christian hope is also the best history of ideas I have had the pleasure of reading... Many of Benedict's short works are each the equivalent of a semester's course in Western thought - such as each of his famous 'September lectures' was (Regensburg, Paris Bernardins, Westminster Hall, the Bundestag, and even the lecture he wrote but never delivered to La Sapienza University...

Spe Salvi: A masterpiece of hope

I am very grateful to Fr. De Souza for marking the tenth anniversary of Spe salvi, perhaps my favorite 'short work' by Benedict XVI. After the stupendous surprise he sprung on us all by his radiant first encyclical Deus caritas est, I did not expect to be swept off my feet by an even more dazzling work which in the process of presenting the reasons for Christian hope is also the best history of ideas I have had the pleasure of reading... Many of Benedict's short works are each the equivalent of a semester's course in Western thought - such as each of his famous 'September lectures' was (Regensburg, Paris Bernardins, Westminster Hall, the Bundestag, and even the lecture he wrote but never delivered to La Sapienza University...

Spe Salvi: A masterpiece of hope

Lyrical and creative, it is the work of a brilliant mind

by Fr Raymond de Souza

Saturday, 9 Dec 2017

Ten years ago Benedict XVI issued one of the more curious encyclicals of recent times,

Spe Salvi (Saved in Hope), about the theological virtue of hope.

The nature of its appearance meant that it has been prematurely forgotten. [????] It shouldn’t be.

It was curious because almost all major papal documents are projects that involve long preparation and many collaborators. Consider

Veritatis Splendor of St John Paul II, some seven years in preparation. Or the mammoth works of Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium and Amoris Laetitia, the longest papal documents in history, so long that they are necessarily and evidently the work of several different drafters.

Spe Salvi was different. The Vatican drafters were at work on the social encyclical that would become

Caritas in Veritate in 2009. Benedict was devoting his spare time, such as a pope has, to his three-volume life of Christ, the first of which appeared in May 2007. But when he returned from his summer sojourn – a holiday it evidently was not – at Castel Gandolfo in the autumn of 2007, Benedict surprised everyone with a complete, polished magisterial meditation on hope.

It was then, confirmed by the second volume of Jesus of Nazareth published in 2011, that it became apparent that Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict was the most learned man alive.

Spe Salvi is uniquely the work of brilliant mind steeped in the Christian tradition, a pastoral heart who knows the aspirations and anxieties of his flock, and the soul animated by the simple piety of the faithful.

While Benedict ranges from ancient to modern philosophy on the nature of hope, it is the Sudanese slave turned Canossian Sister, St Josephine Bakhita – one of John Paul’s Jubilee year canonisations – that he proposes as a model of hope.

Benedict writes:

“Now she had ‘hope’ – no longer simply the modest hope of finding masters who would be less cruel, but the great hope: ‘I am definitively loved and whatever happens to me – I am awaited by this Love. And so my life is good.’ Through the knowledge of this hope she was ‘redeemed’, no longer a slave, but a free child of God.”

Spe Salvi is lyrical in its treatment about how only love can free us from the prison of history as just one damn thing after another.

“To imagine ourselves outside the temporality that imprisons us, and in some way to sense that eternity is not an unending succession of days in the calendar, but something more like the supreme moment of satisfaction, in which totality embraces us and we embrace totality,” he writes. “It would be like plunging into the ocean of infinite love, a moment in which time – the before and after – no longer exists.”

Yet the creativity of

Spe Salvi is not in its treatment of love but justice. Our hope for something more, something beyond this world and across the threshold of death, is not only a desire for a love beyond limits, but also a desire for a limit to evil, a desire for justice. Our hope demands the triumph of justice, which plainly does not prevail in this world.

“I am convinced that the question of justice constitutes the essential argument, or, in any case, the strongest argument in favour of faith in eternal life,” the Holy Father writes. “The purely individual need for a fulfilment that is denied to us in this life, for an everlasting love that we await, is certainly an important motive for believing that man was made for eternity; but only in connection with the impossibility that the injustice of history should be the final word does the necessity for Christ’s return and for new life become fully convincing.”

That God is love has been known since St John wrote it in his epistle. St James writes that mercy triumphs over justice.

Benedict, though, says that the strongest argument for eternal life is not that we might love forever, but that in eternity justice might be wrought for those who were denied it here.

It's as if Benedict XVI had foreseen that the faithful would be sold the false hope of mercy without justice even if he could not have imagined it would come from his successor!

It's as if Benedict XVI had foreseen that the faithful would be sold the false hope of mercy without justice even if he could not have imagined it would come from his successor!

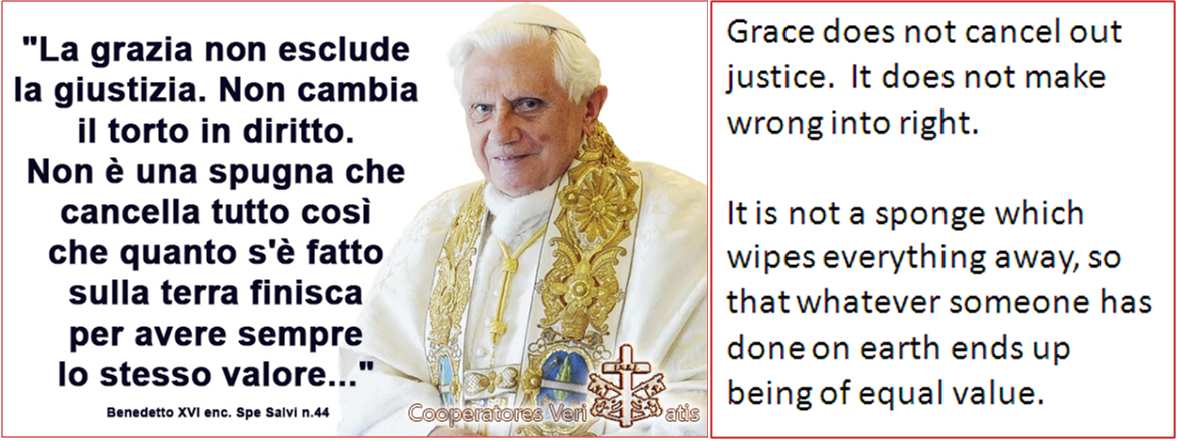

“God is justice and creates justice,” Benedict writes. “This is our consolation and our hope. And in his justice there is also grace. This we know by turning our gaze to the crucified and risen Christ. Both these things – justice and grace – must be seen in their correct inner relationship. Grace does not cancel out justice. It does not make wrong into right. It is not a sponge which wipes everything away, so that whatever someone has done on earth ends up being of equal value.

Dostoevsky, for example, was right to protest against this kind of heaven and this kind of grace in his novel The Brothers Karamazov. Evildoers, in the end, do not sit at table at the eternal banquet beside their victims without distinction, as though nothing had happened.”

What do we hope for? For life, for love, for mercy. But first we hope for justice. In the justice of the Cross we find the hope in which we are saved.

Fr Schall, of course, has written the best essays about Spe Salvi. Here is the two-part essay he wrote when the encyclical was first published in 2007.

by Fr. James V. Schall, SJ

IGNATIUS INSIGHT

December 3, 2007

"Perhaps many people reject the faith today simply because they do not find the prospect of eternal life attractive. What they desire is not eternal life at all, but this present life, for which faith in eternal life seems something of an impediment. To continue living forever — endlessly — appears more like a curse than a gift. Death, admittedly, one would wish to postpone for as long as possible. But to live always, without end — this, all things considered, can only be monotonous and ultimately unbearable."

- Benedict XVI, Spe Salvi, #10.

"Good structures (of society) help, but of themselves they are not enough. Man can never be redeemed simply from outside. Francis Bacon and those who followed in the intellectual current of modernity that he inspired were wrong to believe that man would be redeemed through science. Such an expectation asks too much of science; this kind of hope is deceptive.

Science can contribute greatly to making the world and mankind more human. Yet it can also destroy mankind and the world unless it is steered by forces that lie outside it. On the other hand, we must also acknowledge that modern Christianity, faced with the success of science in progressively structuring the world, has to a large extent restricted its attention to the individual and his salvation. In so doing it has limited the horizon of it hope and has failed to recognize sufficiently the greatness of its task...."

- Benedict XVI, Spe Salvi, #25.

I.

Modern philosophy, particularly political philosophy, has been characterized by mislocating the supernatural virtue of hope.

Philosophy endeavored to incorporate the transcendent order within the world. It gave man, so it surmised, a practical "hope" of a fully happy life as a result of his own efforts through the sciences of man and nature. Thus the virtue of faith became "belief" in progress. The virtue of charity became the effort to rearrange man, family, and polity so that all that separates man from man would be eliminated through no personal effort of the human subjects.

As a result of this tremendous effort of modernity to make philosophy "practical," the classical notions of the last things —d eath, purgatory, heaven, and hell — were likewise relocated within this world. The result has been, at every level, a distortion of man and a failure to understand his real dignity and destiny.

The greatest aberrations of human history have resulted from this effort to reject the Christian understanding of the proper worldly and transcendent purpose of man. Heaven, hell, purgatory, and death appear in new forms.

In

Spe Salvi, the present encyclical on hope, Benedict XVI, with his usual insightful brilliance, re-establishes the proper understanding of the

eschaton, the last things. The place of hope in our lives is grounded in the transcendent destiny of man. He is ultimately to become personally a member of the City of God. Death and suffering remain realities within the human condition. Both can be redemptive. The actual plan of salvation included them, once the Fall occurred.

In a famous phrase, Eric Voegelin characterized the intelligibility of modernity as the "immanentization of the eschaton." By this complicated phrase, he meant that

far from rejecting Christianity, modernity attempted to accomplish the transcendent ends of man, still present in the modern soul as secular hopes, including the resurrection of the body, by means under his own power. Much of the energy devoted to science had this aim as its not so hidden purpose.

What Benedict does in this encyclical is, to coin a phrase, "de-immanentize" the eschaton. That is,

he restores the four last things and the three theological virtues to their original understanding as precisely what we most need to understand ourselves.

These things have been subsumed into a philosophy that denies a creator God. It replaces Him with human intelligence and inner-worldly purpose as the proper destiny of the human race in the cosmos. This effort has simply failed, as Benedict shows in numerous ways. Thus, it is proper to re-present the central understanding primarily of hope. Benedict had already attended to charity in his first encyclical and to

logos, (reason) in his Regensburg Lecture.

II.

John Paul II, among other encyclicals, wrote three devoted to God — one on the Father, one on the Son, and one on the Holy Spirit. Benedict XVI's first encyclical was

Deus Caritas Est, "God is Love". His second encyclical, published on the Feast of St. Andrew, November 30, 2007, was on hope. Its opening Latin words quote from Paul's epistle to the Romans, "By hope we have been saved."

Logically, we probably can expect a later encyclical on "faith." "These three, faith, hope, and charity, but the greatest of these is charity," as Paul wrote in

1 Corinthians 13. Paul is central to the present encyclical on hope.

The basic questions are: "Is there anything to hope for?" and "Are the alternatives to Christian hope tenable?" The answer to the first question is "yes," and to the second "no."

Such a consideration on hope is particularly timely. During the Marxist era, there was a brief period, with the publication of books by Ernest Bloch and Jürgen Moltmann, in which hope was of particular ideological currency. This interest was largely because of the Marxist effort to transfer the transcendent object of hope to this world. Even many Christians were tempted to shift their focus from God to this world. The "eschaton" was to be "immanentized," to use Voegelin's phrase.

That is, following Feurerbach, the Christian idea of everlasting life was all right — its location was just misplaced. It could be achieved in this world by human efforts alone, or so it was thought by not a few great intellectuals. We have no need of a "redeemer" or of "grace."

With

Spe Salvi, Benedict returns to this topic of hope. He is not now so much reacting to a Marxist inner-worldly utopian claim. He is rather looking for

a way to straighten out our minds about the purpose of man both on earth and in his transcendent dimensions.

Benedict wishes to rejoin hope both to its inner-worldly and to its primarily transcendent meanings. He wishes to put to rest once and for all the idea that Christians, by virtue of their transcendent end, neglect the world. It is quite the opposite, as he also shows in

Deus Caritas Est. What is most needed in the world for doing what can be done there is precisely charity and hope.

Benedict XVI is far and away the most learned and incisive mind in the public order anywhere in the world today. He is quite dangerous to public orders and religions that will not see themselves against a criterion of logos, of truth. His initiatives (as this encyclical is one and his "Regensburg Lecture" another) are magisterial. They all include historical, philosophical, theological, and scientific dimensions. He covers the whole sweep of intellectual history. His knowledge of scripture and tradition is profound. For those unbelievers who are weak in their chosen faith, it is best not to read him.

There is nothing that the unbeliever has thought that Benedict has not also thought and, indeed, spelled out in terms at least as clear as any unbeliever himself has set down. He is like Aquinas in this sense. The atheist has nothing to teach him that he has not already thought about and analyzed. His thought has that Germanic thoroughness and clarity that make us aware that he has seen issues in their whole sweep.

This encyclical cites words in Greek, Latin, French, and German, usually words he needs to spell out in technical terms to make a point. In addition to St. Paul and Scripture, it cites — by no means at random — Dostoyevsky, Francis Bacon, Marx, Kant, de Lubac, Horkheimer, Gregory Nazianzen, Adorno, Luther, Bernard of Clairvaux, Aquinas, the Fourth Lateran Council, Saint Hilary, Cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan, Augustine, Maximus the Confessor, Paul Le-Bao-Tinh, pseudo-Rufinus, St. Benedict, Frederick Engels, St Ambrose, Plato, and Josephine Bakhita, a former slave from the Sudan. He already cited Aristotle in the Regensburg Lecture, so he can be excused. He manages to touch on the history of slavery, the notion of modernity, the importance of prayer, and the revitalization of the teachings on Purgatory and Hell, all in one relatively brief document.

In a recent review in Asia Times (November 7, 2007),

"Spengler" remarked that Benedict is the most important man in the world public order today. He is the one man capable of seeing political problems in their theological and philosophical origins. To see politics only as politics is in a way not to see it all. He provides in the public order, as I like to put it, precisely what it most lacks, namely, the intelligibility of what is going on with man in the world. Get this wrong, as we do, and everything else turns against man.

It has been clear for some time, as I have written elsewhere, that

Benedict is the one who explains what the most fundamental issues are that face mankind. Islam is only one of them, though it is a central one. The most important one is the very soul of the West itself and its rejected Christian roots. This act has far more consequences than we are wont to admit.

We are in political confusion because we are in an intellectual and moral confusion. In the Regensburg Lecture, Benedict traced the main issues in modern time back to a Europe that is in the process of losing its understanding of itself by its failure to see the relation of revelation to reason.

The Hebrew, Greek, Roman, and medieval traditions are fundamental for knowing what and where we are. Modernity rejects this tradition because it chooses to do so. There is nothing "inevitable" about it. Evidence that it ought not to do so, however, abounds, especially in its own declining populations. And Europe chooses to do so because it rejects the traditions of reason and revelation out of which it arose in the first place.

III.

The burden of this encyclical is on restoring order to the mind of our kind in thinking about its own destiny.

It is not the elemental spirits of the universe, the laws of matter, which ultimately govern the world and mankind, but a personal God governs the stars, that is, the universe; it is not the laws of matter and of evolution that have the final say, but reason, will, love — a Person. And if we know this Person and he knows us, then truly the inexorable power of the material elements no longer have the last word; we are not slaves to the universe and of its laws, we are free. (#5)

What this encyclical is about, in part, then, is the untenableness of other versions of what man can hope for, particularly modern versions supposedly deriving from science. This "future," I believe, was what Kant asked about. And Benedict in this encyclical pretty much shows the impossibility of Kant's version of an inner worldly alternative to eternal life as the destiny of man. (#19-20)

In a remarkable analysis of both Horkheimer and Adorno, the two famous Frankfurt school thinkers whom the popes treats with great attention, Benedict shows how they, in a way, re-invent Christian concepts of God and eternal life. They even recognize the need for the resurrection of the body, yet in a specifically un-Christian context (#22, 42-43).

The pope suggests that modern thinkers could not get rid of Christianity except by re-inventing it in some odd and contorted manner. The result was never superior to the original. It is time to look again at the original. This is what this encyclical is about.

The pope makes the same point about the Christian background to modern thought in another way by citing Dostoevsky, himself one of the great prophets of our destiny:

Both these things — justice and grace — must be seen in their correct inner relationship. Grace does not cancel out justice. It does not make wrong into right. It is not a sponge which wipes everything away, so that whatever someone has done on earth ends up being of equal value. Dostoevsky, for example, was right to protest against this kind of Heaven and this kind of grace in his novel, The Brothers Karamazov. Evil doers, in the end, do not sit at table at the eternal banquet beside their victims without distinction as though nothing had happened (#44).

In Benedict's view, Plato, in the

Gorgias, had essentially the same idea (525a-24c). Both of these citations relate to the good sense contained in the too much maligned doctrine of Purgatory and the hope it implied, a hope that did not overlook the heinousness of our sins, even when forgiven. This was Dostoevsky's point about the banquet.

The primary candidate in the modern world for what replaces the Christian idea of hope is "progress." This term has both a tenable and an untenable meaning.

Up to that time, the recovery of what man had lost through the expulsion from Paradise was expected from faith in Jesus Christ: herein lay 'redemption'. Now, this 'redemption,' the restoration of the lost 'Paradise' is no longer expected from faith, but from the newly discovered link between science and praxis. It is not that the faith is simply denied; rather it is displaced onto another level—that of purely private and otherworld affairs (#17).

The kingdom of God is now said to be on earth and a product of man's own efforts. Even Kant, the pope noted, suspected that this new kingdom might in fact turn against man (#23). It is very nice to have a pope who reads Kant carefully.

Early in the encyclical, Benedict says that

the Christian message is not only "informative" but "performative" (#2). What does he mean by this? "The Gospel is not merely a communication of things that can be known — it is one that makes things happen and is life-changing." Revelation is, of course, also "informative."

In a very touching comment about parents bringing their child to baptism, the pope recalls what parents ask of baptism. The answer is specifically "eternal life." That is, the parents want to know the real destiny of a real child born into this world whom they know and we know will die. Eternal life is not an abstraction (#10). Continued life in this world, as I cited in the beginning from the same paragraph, simply won't do on its own grounds.

The virtue of hope is a "performative" virtue. It is utterly realistic. It sees that the hope we want is for this individual person. While we want the salvation of all, we want the salvation of each of us. This is not "selfish" but what we are to hope for, precisely death, resurrection, eternal life. This is our sole real end.

"In this sense it is true that anyone who does not know God, even though he may entertain all kinds of hopes, is ultimately without hope, without the great hope that sustains the whole of life" (#27).

Here Chesterton's point that the only real charge against Christianity rings true. It is too good to be true, for it offers what we would want, if we could have it. But it does not promise any other way or route than the way that God has offered to us in Christ, that is, in freedom and suffering. We must choose it.

IV.

Socrates says in the sixth book of the

Republic: "Nobody is satisfied to acquire things that are merely believed to be good, however; but everyone wants the things that really are good and disclaims mere belief here" (505d). Benedict's presentation of the virtue of hope is entirely in conformity with what Socrates says here (#2).

What we believe to be true is true. The guarantee is the presence of Christ in the world.

In a very Augustinian passage, Benedict puts it this way, now in terms of the very education of youth of which Socrates was so concerned:

Young people can have the hope of a great and fully satisfying love; the hope of a certain position in their profession, or so some success that will prove decisive for the rest of their lives. When these hopes are fulfilled, however, it becomes clear that they were not, in reality, the whole. It becomes evident that man has need of a hope that goes further. It becomes clear that only something infinite will suffice for him..." (#30)

The story of modern youth, in this sense, is the story of disappointment over any alternative but the one that lies at the origin of their creation, that of eternal life.

The alternative utopias and destinies do not cohere.

"This is simply because we are unable to shake off our finitude and because none of us is capable of eliminating the power of evil, of sin which, as we plainly see, is a constant source of suffering. Only God is able to do this; only God who personally enters history by making himself man and suffering within history" (#36). Here we find that the actual hope given in revelation when spelled out describes our condition better than any "rationalistic" alternatives: eternal life (#12).

V.

Let me conclude these preliminary remarks on the encyclical on hope by pointing out how Benedict distinguishes progress in terms of science and the same idea in the field of morals and ethics (#24-25). There can be no "progress" in the field of ethics or politics because each person must himself decide what he will do. We do not exist as one "corporate" being, but as many within the same nature.

"Man's freedom is always new and he must always make his decisions anew. These decisions can never simply be made for us in advance by others — if that were the case we would no longer be free."

Human beings in each of their acts are free. They could choose to do otherwise. If they are bad, they can choose to be good, or to be bad.

"Freedom presupposes that in fundamental decisions, every person and every generation is a new beginning. Naturally, new generations can build on the knowledge and experience of those who went before, and they can draw upon the moral treasury of the whole of humanity. But they can also reject it, because it can never be self-evident in the same way as material inventions." The very doctrine of the eternal salvation of each individual person as an acceptance or rejection of what is given to him depends on this basic principle.

Benedict is careful not to place himself in an individualist position. Man is a political and social animal, even in his salvation. But structures alone cannot save him. The hypothesis that they can, one of the tenets of modernity, is precisely a denial of the freedom that makes eternal, not to mention daily, life worthwhile.

"Freedom must constantly be won over for the cause of good. Free assent to the good never exists simply by itself. If there were structures which could irrevocably guarantee a determined—good—state of the world, man's freedom would be denied, and hence they would not be good structures at all." It is at this point that Benedict cites Francis Bacon in the passage found at the beginning of this essay. To repeat, "man can never be redeemed simply from outside."

What is perhaps amusing about this encyclical is that Benedict simply takes the oft-derided notion of Purgatory and shows how and why it is a perfectly sensible doctrine, one that has sensible philosophical and psychological origins. Most of us, he recalls, are neither wholly good nor bad, and we die that way. It is not irrational to think that a period of purgation is not good for us, in view of our final end (#45). Nor have we gotten rid of the notion of hell. We just re-invented it in our thinking of totalitarian regimes, themselves the product of the darker side of modernity.

Again let me recall the spirit of this encyclical:

"In the modern era, the idea of the Last Judgment has faded into the background. Christian faith has been individualized and primarily oriented towards the salvation of the believer's own soul, while reflection on the world history is largely dominated by the idea of progress. The fundamental content of awaiting a final Judgment, however, has not disappeared; it has simply taken a totally different form" (#42).

Spe Salvi is given to us to show that the original form remains the really reasonable one. Benedict has indeed "de-immanentized the eschaton."

He has returned politics to where it should be in this world as a limited effort to do what we can for one another, now motivated by a caritas and a gratia that did not exist without the divine intervention.

But our end, for each of us, remains transcendent. We seek not just our personal salvation and resurrection, but also that into eternal life, the City of God. "Paul reminds the Ephesians that before their encounter with Christ they were 'without hope and without God in the world'

(Eph 2:12)." (#2)

We have failed to understand the "greatness of our task" (#25). We are not without hope in the world because we are not without God. By testimony of the futile search in modernity for the "immanent eschaton" itself, no other alternative exists but that of our hope to be saved.

As Paul says in 1 Thessalonians, we are not to "grieve as others do who have no hope." How unerring is Benedict's sight to see that it is precisely the virtue of hope that gets to the bottom of what most unsettles the modern mind.