Here is a review by Fr. Rutle rof George Weigel's third biographical volume on John Paul II... Don't be put off by the inexplicably frivolous title

Here is a review by Fr. Rutle rof George Weigel's third biographical volume on John Paul II... Don't be put off by the inexplicably frivolous title

that the Herald chose to give it.

St John Paul II was a sublime visionary,

but had an Achilles heel

by Fr George Rutler

Oct. 20, 2017

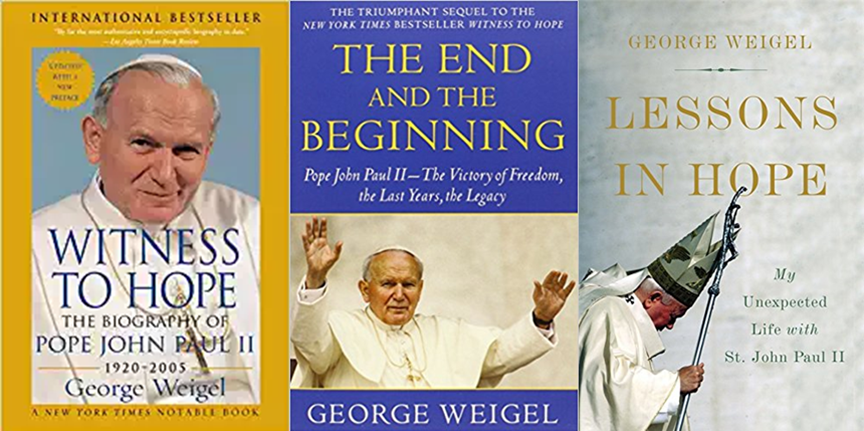

George Weigel’s

Witness to Hope was written before its subject was canonised, but that exhaustive biography vibrated with confidence that the day of universal recognition would be inevitable. Weigel has become something of a pontifical Boswell, and his third volume about John Paul II is like the last wing on a vivid triptych by Memling or Rubens.

The first two books were analytical, while this one –

Lessons of Hope (Basic Books, £25) – is a portrait more ruminative and personal, and not without humour. It may even be more valuable precisely for that. History is disserved by those who think that private asides and impressions are secondary to major dates and deeds.

Weigel’s classical theological formation and his own urbane humanism made him a good fit for understanding Karol Wojtyła, and it would seem that the Holy Father sensed the same, enjoying his company and table talk. Through that association, Weigel was able to perceive the pope’s sources and initiatives, beginning with his pastoral work in Poland.

Wojtyła’s Polishness was not something to be thrust aside when he became Universal Pastor, like some gnostic shedding of irrelevant skin. Poland was an icon of Christ in its heroic deeds and salvific suffering, far more than most nations. That land, with trembling borders but unflagging chivalry, was crucified over centuries, only to rise with valour when its people cried out in 1979: “We want God.” And Wojtyła was there to hear them.

Carl Jung spent considerable effort trying to explain a dimension he called “synchronicity”, commonly shrugged off as mere coincidence. For the Christian, that dimension is often Divine Providence at work, and it would be pedantic to think that Wojtyła’s early suffering and experience of socialised atheism were not part of a supernatural scheme to prepare him for the papacy. Weigel’s familiarity with Polish culture may be the most important theme in what he writes of hope.

Another subject for another day is

how the theological dissidents and dilettantish revisionists who patronised Wojtyła and loathed Ratzinger burrowed into the cultural underground, suborning the media and academies, waiting for their moment which, if tenuous and fragile, they think had arrived. The geriatric modernists are breathing fresh air, and the test will be how long their moment will actually last.

With scholastic realism, John Paul II believed that, in theology, 2+2 = 4. He did not subscribe to a Hegelian synthesis whereby truth is what is left after “making a mess”. His Theology of the Body was of a vision loftier and more demanding than instruction in how to kiss.

If anyone could express that even more clearly than Wojtyła it was Ratzinger, whose masterful articulation confounded all stereotypes of German obscurantism. John Paul evidently recognised that himself, which he is why he relied on him so much, and that may have been another instance of the wheel of Providence at work.

Both of them were like Bunyan’s pilgrim contending against “dismal stories” but

they did so without subjecting doctrine to casuistry, or condescending to rudeness and insults.

The way John Paul focused on the horizon may at times have distracted him from what was going on around his doorstep. His episcopal appointments sometimes were perplexing and his idealism beclouded his willingness to acknowledge abuses within the clerical system.

My friend Fr Stanley Jaki once expressed to me his caution that phenomenology might be Wojtyła’s Achilles heel rather than the strength of his philosophical narrative. It is curious that such a sublime visionary should have been remarkably atonal in matters liturgical and artistic. His pontificate boasted no Borromini, and its cultural landscape was pockmarked with such offences as the Jubilee Church in Rome, the Divine Mercy Shrine in Kraków, Los Angeles Cathedral and the pharaonic John Paul II Cultural Center in Washington DC.

With John Paul II and Benedict XVI now distant if venerable echoes, and even censored in some quarters, we find ourselves now much like Bernard of Chartres’s

nanos gigantum humeris insidentes – dwarfs on the shoulders of giants.

Weigel’s generous spirit hoped for the best when the Church’s present ambiguities and unprecedented confusions began. He is enough of an authority about hope to know that hope is sturdier than optimism. While his completed triptych goads the reader to realise what great things the Holy Spirit has done, it also makes us something like the men in their doldrums on the Road to Emmaus. But there is still the Lord reminding us that all these things had to have happened.

These are perplexing and even scandalous days for the faithful. But if Bernard of Chartres thought himself a mere afterthought and unworthy heir, his image of dwarfs on the shoulders of giants is radiantly depicted in the south transept window of Chartres cathedral whose glorious construction began just a few years after he died. That then vindicates hope as a virtue, more than optimism as a wish.

Weeks ago, CWR published an interview with George Weigel by its editor Carl Olson but that was when I was hors de combat. But it's not too late to post it:

George Weigel on the 'lessons in hope'

he received from John Paul II

The papal biographer’s new book describes his relationship with Pope John Paul,

as well as the great challenges the pope faced in the final years of his life

Interview by Carl Olson

September 18, 2017

George Weigel’s two biographies of St. John Paul II —

Witness to Hope and

The End and the Beginning — are widely considered the authoritative volumes on the life and work of the Polish pope.

Weigel has a new book out,

Lessons in Hope: My Unexpected Life with St. John Paul II (Basic Books), which focuses on his decades-long friendship with St. John Paul and on the inspiring witness the pope offered the world in the face of great suffering in the last years of his life.

Weigel recently spoke to CWR editor Carl E. Olson about his new book.

At the start of Lessons in Hope, you note that you thought Witness to Hope and The End and the Beginning, which totaled about 1,600 pages, contained all you could or would say about St. John Paul II. Why this third book? In what ways is this “album of memories,” as you describe it, different from the two biographies?

Lessons in Hope is almost entirely anecdotal; it tells the stories that wouldn’t have “fit” into two volumes of biography, but that illuminate, in one way or another, interesting facets of John Paul II’s personality and way of conducting the papacy. I’ve discovered in recent years that this is what people want, now: not so much analysis of a remarkable personality and his accomplishment, but story-telling that brings him alive in a personal way.

You write that the “experience of learning John Paul II and his life taught me a new way of looking at events in my own life…” What are some examples of that? And what are some of the events that paved the way for you to become John Paul II’s biographer?

At Fatima in 1983, one year after the assassination attempt that came within a few millimeters of taking his life, John Paul said, “

In the designs of Providence, there are no mere coincidences.” What we think of as “coincidence,” or just happenstance or randomness, is actually a part of God’s providential guidance of history that we just don’t understand yet.

That insight of his helped me to see how, for example, my philosophical and theological studies in college and graduate school, my work as a columnist and essayist, the people I met at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in 1984-85, and a week in Moscow in 1990 fomenting nonviolent revolution were all providential experiences that prepared me to take on the job of being John Paul II’s biographer.

One point made in several places is the importance of understanding John Paul II’s philosophical perspective and project. What are some key features of his philosophical work? And how has this been either misunderstood or even misrepresented?

John Paul II is persistently misunderstood as some sort of pre-modern mind, when in fact his was a thoroughly modern mind with

a distinctive critique of modernity. At the heart of that critique was

- the conviction that ethics had come unglued from reality;

- that the moral life was wasting away into subjectivism and sentimentality; and

- that human beings (and society) were suffering as a result.

The entire philosophical project he and his colleagues at the Catholic University of Lublin launched in the 1950s was an attempt to get the moral life back on a sound footing: not from top down but from bottom up —through a rigorous and compelling theory of the human person, our capacity for responsibility, and the dynamics of our moral decision-making. That’s why his philosophical masterwork was called “Person and Act.”

How did you first meet John Paul II and how did your friendship develop?

Our first real conversation was in September 1992, when I gave him a signed copy of

The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism, which he had already read on galley proof. Things snowballed after that, both in terms of personal conversations and correspondence, and both conversation and correspondence continued after the publication of

Witness to Hope. The details of how our relationship evolved over the course of my preparing

Witness to Hope and afterwards — during the dramas of the Long Lent of 2002, the Iraq War, and his last illness — are described in detail in

Lessons in Hope.

John Paul II strongly encouraged you to meet with many of his friends from his time in university. Why was that so significant to him? How did that period of time shape the rest of his life?

It was not so much his friends from his own time in university (although I did meet with the surviving members of his underground wartime theatrical troupe, the Rhapsodic Theater), but the friends he made while he was a university chaplain in the late 1940s and early 1950s. As he was helping form them into mature Catholic adults, they were helping form him into one of the most dynamic and creative priests of his generation. He thought that story was crucial to understanding him “from the inside,” so he encouraged me to talk with these men and women, several of whom are now close friends of mine.

You emphasize, as you have many times over the years, that your two biographies of John Paul II were not “authorized biographies.” What does that mean and why is it so important?

An “authorized biography,” in the usual sense of the term, is one that has been vetted (and perhaps edited) by the subject or the subject’s heirs, in exchange for access and documents; so an authorized biography should be read with a certain reserve, given what one has to assume was the vetting involved.

At the very outset of the

Witness to Hope project, I told John Paul over dinner that he couldn’t see a word of what I wrote until I gave him the finished copy of the book, and he immediately responded, “That’s obvious.” He knew, as I knew, that there could be no one looking over my shoulder as I wrote if the book was to be credible; he also thought that the book was my responsibility and he wasn’t about to change a lifelong pastoral habit of challenging others to be responsible without imposing his own judgments.

So while I hope

Witness to Hope and

The End and the Beginning are as authoritative as possible, they are in no sense “authorized.” I also hope that L

essons in Hope ends, once and for all, the urban legend that John Paul II asked me to write his biography. He didn’t. I suggested the project and he agreed to cooperate with it.

What were some of the more challenging aspects of researching the life of John Paul II?

There were a lot of people in the Roman Curia who weren’t as eager for me to have full access to people and documents as John Paul II was, and the stories of my adventures in getting through that Italianiate obstacle course are very much part of

Lessons in Hope.

[That would explain Weigel's habitual negative appraisals of the 'Roman Curia' as a whole.]

Then there were the problems posed by my predecessors in the papal biographers’ guild, like Tad Szulc and Carl Bernstein: people who had spoken freely with them felt that they had been burned, in the sense that Szulc and Bernstein had slotted their reflections into what these men and women who knew John Paul II well thought were nonsensical analyses. And it took a while for me to convince some of them that I was different.

There was also the challenge of inviting a man with a deep sense of privacy to talk about aspects of his life he had rarely if ever discussed before; but John Paul answered every question I posed to him and in fact pushed me into exploring areas of his life to which I might otherwise have given short shrift.

In discussing the “Long Lent” — the clerical sexual abuse scandal that broke in early 2002 — you explain that there existed an “information gap” between Rome and the United States. Why did that gap exist? How well or poorly was John Paul II informed of what was happening?

The gap existed because of curial incapacity and the general Roman sense that “things can’t be as bad as all that,” which is too often applied to crises. The story of how the Pope got more fully informed of the situation, and my role in helping facilitate that, is told in detail in

Lessons in Hope.

What are some lessons from John Paul II that you think are especially apt now, in 2017?

In this time of turbulence in the Church, it’s important to remember that we’re not in 1978.

The growing parts of the Church throughout the world are the parts of the Church that have embraced what I’ve come to call “all-in Catholicism” as exemplified by the teaching of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, and the dying parts are those parts that continue to embrace Catholic Lite.

This distinction is true of pastoral life, Catholic intellectual life, and the Church’s public witness. And that makes for a very, very different circumstance than the situation in 1978, when Catholic Lite pretty well ruled the roost.

Catholic Lite is a failure and has no future; there is a compelling alternative to it, created by the Second Vatican Council as authoritatively interpreted by John Paul II; and if we all remembered that, things would be a little calmer these days.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 23/10/2017 03:46]