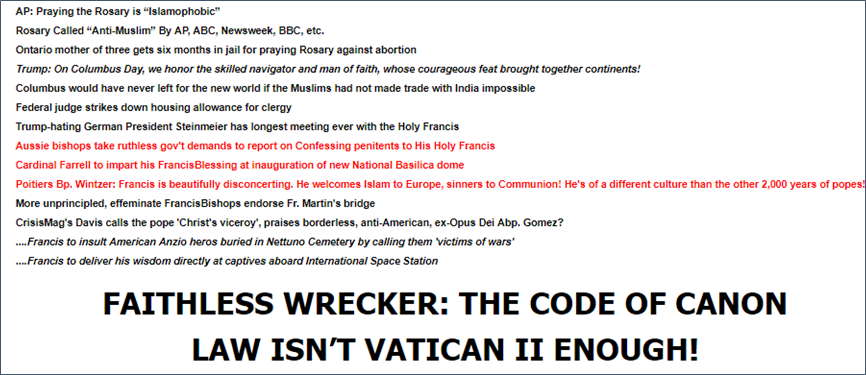

October 9, 2017 headlines

Canon212.com

PewSitter

PewSitter

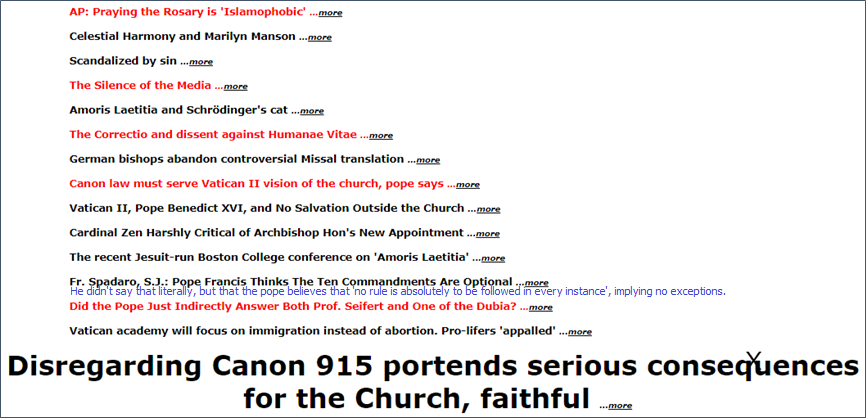

Disregarding the divinely-rooted Canon 915

Disregarding the divinely-rooted Canon 915

portends serious consequences for the Church and her faithful

Its object in prohibiting Communion for unqualified remarried divorcees

is to protect the faith community from scandal – but everyone seems

to be ignoring it in all the debates over the dubious points of AL

October 9, 2017

For several years I and others have argued that the question of admitting divorced-and-remarried Catholics to holy Communion turns primarily on Canon 915 (which norm, against a backdrop of canons protecting the right of the faithful to access the sacraments, sets out a minister’s duty to refuse holy Communion under certain conditions).

Asserting the importance of Canon 915 in this Communion discussion, however, has been an uphill battle as

virtually none of the official documents central to this debate—including Amoris laetitia,the Buenos Aires letter, the Maltese directives, the German episcopal conference document, and several others—so much as mentions Canon 915, let alone do they recognize that this canon directly regulates the sacramental disciplinary question at hand.

Till now I have but briefly noted the obligatory force of Canon 915 in terms of its being part of a Code of canons which “by their very nature must be observed” especially in that they are “based on a solid juridical, canonical, and theological foundation.”

(John Paul II, Sacrae disciplinae leges (1983) [¶ 19]). Faithful Catholics should need little incentive to follow a canon beyond the fact that the Legislator has made it a part of his universal law.

Discussions as to the proper interpretation of a law are to be expected, of course, but such discussions would always center on a canon that all sides recognized existed and was relevant.

In the wake of Amoris, however, something different is happening: Canon 915 is slowly becoming an Orwellian “uncanon”, its existence not mentioned in key official documents impacting the Communion debate, its relevance to the precise sacramental issue at hand not being acknowledged. This notable official silence concerning Canon 915 portends, I suggest, serious consequences for the debate over the admission of divorced-and-remarried Catholics to holy Communion, to be sure, but, unless checked, it will also negatively impact other looming issues wherein Catholic doctrine directly interfaces with canonical discipline.

In light of the foregoing, then, I want to develop a point about Canon 915 that, while implicit in my earlier discussions of the Communion admission issue, seems now must be more explicitly made, namely, that

the obligation to observe the sacramental provisions set out in Canon 915 when considering the administration of holy Communion to divorced-and-remarried Catholics rests not only on that norm’s inclusion in a set of positive ecclesiastical laws but on its reflecting universally binding divine law itself.

Part 1 - The divine law roots of Canon 915

The canonist in me would be content to note that the character of Canon 915, as a modern articulation of a divine law precept that dates back to St. Paul and/or that aims at preventing divinely-forbidden scandal, is expressly and resoundingly upheld in

- a declaration on Canon 915 issued by the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts in 2000 and, further,

acknowledged by numerous canonical commentaries including

- the Exegetical Commentary (2004) III/1: 614-615;

- Code of Canon Law Annotated (2004) 709; and

- Codice di Diritto Canonico Commentato (2009) 767, to name just three.

There being zero question among canon lawyers that Canon 915 deals directly with the question of admitting, here, divorced-and-remarried Catholics to holy Communion, I would turn promptly to Canon 915 for directions.

But additional, more theological, foundations for demonstrating the divine law basis of Canon 915 are available.

The

Catechism of the Catholic Church 2284-2287, for example,

outlining the respect owed to the immortal souls of others, identifies scandal as “an attitude or behavior which leads another to do evil”, teaches that scandal “takes on a particular gravity by reason of the authority of those who cause it”, notes that scandal can be given by policies “leading to the decline of morals and the corruption of religious practice”, and warns community leaders that using their power “in such a way that it leads others to do wrong” makes them “guilty of scandal and responsible for the evil that he has directly or indirectly encouraged.”

Per the Catechism, then, individuals giving personal scandal to others violate divine law; Church officials giving institutional scandal to the community (say, by countenancing the personal scandal given by certain individuals) violate divine law more gravely still.

Furthermore, by prohibiting ministers of holy Communion from giving that “most august Sacrament” (1983 CIC 897) to any Catholic who “obstinately perseveres in manifest grave sin” (understanding those terms as they have long been understood in canon law), Canon 915 serves the common ecclesial good in, I suggest, at least three ways:

- first, it supports to some extent the faithful’s personal obligation under Canon 916 to examine their consciences (perhaps with the guidance of a confessor) prior to approaching for holy Communion;

- second, it reduces, though it does not eliminate, the chances that sacrilegious Communions will be made by the faithful;

- third—and most importantly, I suggest—it directly prevents ministers of the Church from giving institutional scandal to the faith community (and indeed to the wider watching world) such as would inevitably arise if the Church’s greatest sacrament were administered to Catholics whose observable conduct or status (such as, say, living together with another as if a spouse although at least one person in the relationship already was already married) contradicts core values of the faith (here, Christ’s repeated proclamations against divorce and remarriage).

In short,

Canon 915 blunts the individual scandal given by the faithful who openly live lives contrary to fundamental Christian values and it prevents Church officials from giving institutional scandal by engaging in ministerial actions that would appear to treat such contrarian behavior as compatible with Church teaching.

But the problem of disregarding Canon 915 goes deeper still, I fear.

Into the void created by ignoring Canon 915, a canon fashioned over many centuries as a community defense against scandal and specifically against scandal given by ecclesiastical leaders, there has rushed in

the contrary idea that the private judgement of individuals (perhaps reached with priestly advice) concerning their taking of the Sacrament, whenever they consider themselves fit for it and regardless of how inconsistent their public conduct or status might be with the teachings of Christ and his Church, is to be preferred to the common ecclesial good of protecting the faith community from the harm of public bad example. In other words,

personal conscience is being urged as a substitute for public conduct as a key criterion controlling certain questions of ecclesiastical governance.

Moreover, this abandonment of the faith community to the dangers of scandal contrary to the divine law protections reflected in Canon 915 is presently being pushed in regard to Catholics living in “public and permanent adultery” (CCC 2384) but the logic of substituting personal conscience for public conduct in regard to ecclesial governance issues does not and will not stop at marriage questions.

Part 2: How the problem took hold and is spreading

That the question of admitting divorced-and-remarried Catholics to holy Communion should henceforth turn largely on an individual’s perception of (diminished or even absent) personal culpability for sin as that might be discerned in personal conscience, and need not honor primarily the divine law prohibition against giving personal and institutional scandal to others, is a proposal so startling in its novelty and so shocking in its implications that it seems to have taken over, almost invisibly, the very framing of the question of admitting divorced-and-remarried Catholics to holy Communion. It is as if the world of sacramental discipline groaned and awoke to find itself subjectivized.

Now,

this erosion of the canonical protection of the faith community against scandal is not being achieved by a frontal attack on Church teaching (indeed Church teaching is often verbally honored) nor so much by turning a blind eye toward disciplinary abuses (as has always been with us), but rather, first, by the simple expedient of pervasively ignoring Canon 915 and its scandal-prevention orientation, and second, by treating the norm (if it must be mentioned at all, and which must, one supposes, deal with something) as if it dealt with the Church’s (in itself, quite legitimate) pastoral concern for sin, as follows:

First, as noted above, mention of Canon 915 itself has been almost completely absent from the most important documents dealing with the question of admitting divorced-and-remarried Catholics to holy Communion. But, realizing that admitting divorced-and-remarried Catholics to holy Communion is somehow “not okay” canonically, some mechanism for addressing that “not okay-ness” needed to be developed.

That mechanism is, I suggest, the constant repetition of certain tropes or themes according to which Canon 915 (or at least some unnamed law dealing with the faithful going to Communion), deals largely with questions of personal sin, not scandal.

Once the conversation about Canon 915 (or some unnamed restrictive norm) has, by the steady repetition of nearly invariable refrains, been shifted away from this norm’s primary task of protecting the community against scandal and toward its allegedly being a response to personal sin, the rest proceeds easily:

Upon correctly pointing out, say, that divorced-and-remarried Catholics are often in situations of reduced moral culpability and after rightly stressing the pastoral importance of weighing case-by-case factors in pastoral accompaniment—and being careful to avoid acknowledging that such considerations have basically nothing to do with the operation of Canon 915,

a norm concerned with the prevention of objective scandal, not internal assessments of conscience —

the conclusion comes gradually to be accepted that, as no law or human being can judge another’s culpability for sin, so no law or human being may prohibit another from taking Communion based on that other’s “culpability” for conduct.

Ministers of Holy Communion thus become sacramental ATMs. To the minister’s prompt, “Body of Christ”, a Catholic responds with the password “Amen” [although of course, one is not supposed to say Amen to the priest’s words when he administers the Eucharist], and the Eucharist is disbursed. Scandal is ignored; Canon 915 is diverted; and the community is left to deal with the effects of the bad example of others and of their ministers as best it can.

In short, once people think that Canon 915 (the few times it is mentioned) is

mostly about assessing the sacramental consequences of the personal sins of the faithful and is not concerned with preventing institutional scandal by ministers, then anything that mitigates one’s culpability for personal sin (and many things do mitigate such culpability) necessarily mitigates the force of Canon 915.

The subversion of the Communion debate concerns over scandal is complete, and its resolution in favor of a highly subjective determination of eligibility for holy Communion is achieved.

A final note

There is, alas, another consequence of wrongly framing the question regarding the admission of divorced-and-remarried Catholics to holy Communion as if it were [merely] a question of culpability for sin instead of it turning on the community’s right to be protected from personal and institutional scandal.

It is this: in consequence of the urgent need to reorient the debate over Canon 915 back toward protecting the faith community against scandal as required by divine law, the discussion of many other pressing pastoral questions on marriage (such as the terrible ill-preparedness of so many people to enter marriage, the inadequacies of certain canonical formulations of various points of marriage doctrine, the correct operation of the ‘internal forum solution’, the worsening anomalies of requiring canonical form for valid marriage, the procedural problems of the older canon law on annulments and of Francis’ newer norms, and a dozen points besides) is repeatedly delayed.

Because of the need to respond to the deeper threat to ecclesial order that ignoring and misrepresenting Canon 915 poses to the Church, people calling attention to Canon 915 are dismissed as legalists for their harping on esoteric laws while there are real people with real marriage problems to be tended.

As if we didn’t know that, and as if we didn’t prefer to make positive contributions to the pastoral advancement of canon law instead of having, nearly constantly these days, to take time out to defend norms such as Canon 915, and the very important values they represent, against destruction by those unaware of, or not concerned with, what such canons mean “in the life both of the ecclesial society and of the individual persons who belong to it.”

(John Paul II, Sacrae disciplinae leges (1983) [¶ 16]).

If you still doubt that there is method in Bergoglio's hubristic madness, consider the ff story, in the light of Ed Peters's eye-opener on the systematic 'shelving' of Canon 915 by the Bergoglians. Now, it seems he is bent on turning all of canon law on its head to suit his agenda. This pope is acccelerating his demolition of the one true Church and replacing it with his own church which he presumptuously dares to still call the Catholic Church.

Pope says canon law must serve

Vatican II vision of the Church

[For this pope, of course, the vision is that of total rupture

with the past - what hermeneutic of continuity?]

by Cindy Wooden

CATHOLIC NEWS SERVICE

Oct. 9, 2017

ROME - The Catholic Church’s Code of Canon Law is an instrument that must serve the church’s pastoral mission of bringing God’s mercy to all and leading them to salvation, Pope Francis said.

Just as the first full codification of Catholic Church law was carried out 100 years ago “entirely dominated by pastoral concern,” so today its amendments and application must provide for a well-ordered care of the Christian people, the pope said in a message Oct. 6 to a canon law conference in Rome.

Leading canonists, as well as professors and students from all the canon law faculties in Rome, were meeting Oct. 4-7 to mark the 100th anniversary of the first systematic Code of Canon Law, which was promulgated by Pope Benedict XV in 1917.

Work on the code began under the pontificate of St. Pius X and was a response in part to the need to examine, systematize and reconcile often conflicting church norms, Francis said.

After the Vatican lost its temporal power, he said, St. Pius knew it was time to move from “a canon law contaminated by elements of temporality to a canon law more conforming to the spiritual mission of the church.”

The 100th anniversary of the code, which was updated by St. John Paul II in 1983, should be a time to recognize the importance of canon law as a service to the church, Francis said.

When St. John Paul promulgated the new law, the pope said, he wrote that it was the result of an effort “to translate into canonical language … the conciliar ecclesiology,” that is, the Second Vatican Council’s vision of the church, its structure and relation to its members and the world.

“The affirmation expresses the change that, after the Second Vatican Council, marked the passage from an ecclesiology modeled on canon law to a canon law conforming to ecclesiology,” Francis said.

The Church’s law must always be perfected to better serve the church’s mission and the daily lives of the faithful, which, he said, was the point of his amendments to canon law streamlining the church’s process for determining the nullity of a marriage.

Canon law, he said, can and should be an instrument for implementing the vision of the Second Vatican Council.

In particular, Francis said, it should promote

- “collegiality;

- synodality in the governance of the church;

- valuing particular churches;

- the responsibility of all the Christian faithful in the mission of the church;

- ecumenism;

- mercy and closeness as the primary pastoral principle;

- individual, collective and institutional religious freedom;

- a healthy and positive secularism; (and)

- healthy collaboration between the church and civil society in its various expressions.”

[He touches all the code words of his pontificate - using seemingly unexceptionable terms to mask his ruinous agenda.]

Also very apropos is Ed Peters's earlier comment on a 'new' defense of AL in the light of the CORRECTIO, in which he points out how the defender Rocco Buttiglione, appears to ignore canon 915 altogether, in addition to other canonical errors :

A corrective to some of Prof. Buttiglione’s

recent assertions about canon law

He has misunderstood and/or misrepresented some important, if more subtle,

canonical points in his recent critique of the Correctio Filialis.

October 6, 2017 Edward N. Peters

October 6, 2017 Edward N. Peters

It is simply not possible for me to re-explain, every time I address the latest canonical misstatements proffered by some writer or another, the whole canon law on the reception of holy Communion and the administration of that Sacrament by ministers. Further information on those crucial topics is available elsewhere.

Here I comment only to caution others that some of Prof. Rocco Buttiglione’s recent comments on the administration and reception of holy Communion are not canonically sound. [In the light of Bergoglio's virtual dismissal of existing canon law as mutable by his will and fiat, perhaps his apologist Buttiglione does not care about existing canon law, either!]

Readers might recall that a year or so ago Buttiglione authored an essay alleging that divorced-and-remarried Catholics had been excommunicated until John Paul II courageously eliminated that supposed sanction from the 1983 Code. I showed that no such excommunication existed in universal law (searching back more than 100 years) and suggested then that Buttiglione was not a reliable historian of canon law. To my knowledge he did not modify his claims. Oh well.

Now Buttiglione has authored another essay, this time against the Correctio Filialis. As stated earlier I have no position on the Correctio itself but I pause to suggest that, once again, Buttiglione has misunderstood and/or misrepresented some important, if this time more subtle, canonical points. Our discussion is hampered by Buttiglione’s failure to specify exactly which disciplinary norms he has in mind at various stages of his essay. Sorry, we’ll proceed as best we can.

For example, Buttiglione writes:

There is an absolute impossibility of giving Eucharist to those who are in mortal sin (and this rule is of Divine law and therefore imperative) but if, due to the lack of full knowledge and full consent, there is no mortal sin, communion can be given, from the point of view of moral theology, also to a remarried-and-divorced.

There is also another prohibition, not moral but legal. Extra-marital coexistence clearly contradicts the law of God and generates scandal. In order to protect the faith of the people and strengthen the conscience of the indissolubility of marriage, legitimate authority may decide not to give communion to remarried-and-divorced even if they are not in mortal sin. However, this rule is a human law and the legitimate authority can allow exceptions for good reason.

There are many canonical mistakes in the above passage though I will deal with only three at present. Also I will rephrase some of Buttiglione’s words because I think bad translations might have interfered with his message.

(1) There is an absolute impossibility of giving the Eucharist to those who are in mortal sin. [Even plain common sense tells us this is FALSE! A priest administering communion does not know who is in mortal sin and thereby committing sacrilege by receiving Communion!]

This claim is wrong. Setting aside the impossibility of one human being knowing for sure whether any other human being is “in mortal sin” — why do so many people think that reading souls is part of a canon lawyer’s stock-in-trade? — it is quite possible, indeed,canonically required, to administer holy Communion publicly to members of the Christian faithful whom a minister suspects (perhaps on excellent evidence) to be “in mortal sin” unless all five elements of Canon 915 (obstinate perseverance in manifest grave sin) are simultaneously satisfied.

This is standard sacramental law, yet Buttiglione seems unaware of this norm and unaware that Canon 18 requires its strict interpretation such that, doubtless and sadly, sacrilegious Communions can be made in accord with Church law — something hardly possible if divine law absolutely prohibited it. This botching of a crucial point in his argument does not instill confidence that Buttiglione will handle other points reliably.

(2) Extra-marital cohabitation clearly contradicts the law of God and generates scandal.

Sometimes false. I am aware of no divine law that prohibits “extra-marital cohabitation” per se (let one alone “clearly” prohibiting it) and can imagine situations wherein such “cohabitation” (not extra-marital sex, but cohabitation), strictly speaking, could be prudently countenanced, at least for a time (complex discussion omitted).

Rather I suspect that Buttiglione is, wittingly or not, confusing “cohabitation” with “divorce-and-remarriage” and thereby substituting what the Catechism of the Catholic Church 2384 describes as “a situation of public and permanent adultery” for something that mightbe morally acceptable. Again, such an assertion hardly exhibits the level of precision that discussion of these points requires.

(3) To protect the faith of the people and to strengthen the respect for the indissolubility of marriage, legitimate authority may decide not to give communion to remarried-and-divorced even if they are not in mortal sin. However, this rule is a human law and the legitimate authority can allow exceptions for good reason.

Again Buttiglione assumes that ministers and canonists know who is “in mortal sin” and who isn’t. For the last time, that’s balderdash. But more to the point, Buttiglione’s earlier erroneous assertion that divine law always prohibits ministers from giving holy Communion to persons “in mortal sin” (assuming we even know who they are), returns now to create new confusion between canons resting on divine law (as some do) and canons supposedly resting on mere human law (such as, one surmises, Buttiglione believes Canon 915 does when it prohibits administration of holy Communion to divorced-and-remarried Catholics) which law, because it is ‘just a law’, and not ‘morals’, can supposedly be changed.

But, as has been explained numerous times, Canon 915, operating in the face of obstinate perseverance in manifest grave sin (here, the sin of contradicting the permanence of marriage by purporting to marry again while a prior spouse is yet alive), prohibits ministers from giving holy Communion to certain persons when such administration causes scandal to others, scandal being defined by the Catechism as “a grave offense” which is worsened “when given by those who by nature or office are obliged to teach and educate others”. (CCC 2284-2287). In other words, Canon 915 rests at least in part on divine law, the divine law that prohibits, among other things, anyone (especially ministers of the Church!) from giving scandal to others. Buttiglione seems unaware of this aspect of Canon 915.

Canon 915 is not about withholding holy Communion from a couple that one thinks is illicitly “doing it”; it is about withholding holy Communion when its administration would lead the community to, here, doubt the gravity of the contradiction that civil divorce-and-remarriage gives to marriage as proclaimed by Christ and his Church.

Even the much-invoked and usually misunderstood “brother-sister” accommodation is to be considered only if the couple’s status as divorced-and-remarried outside the Church is not known in the community (and if the couple promises continence which, obviously, ministers cannot monitor).

But at this point, I must repeat that these wider matters are explained elsewhere, and my focus now is on Buttiglione’s latest essay, which essay, I think I have shown, is not a reliable guide to the canonistics in question here.[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 10/10/2017 19:57]