Early on, the ravening unrelenting blood lust of BLMania homed in on tearing down statues of 'white Jesus' which speaks of the appalling ignorance, real as well as feigned, that the BLManiacs all seem to share. If

Early on, the ravening unrelenting blood lust of BLMania homed in on tearing down statues of 'white Jesus' which speaks of the appalling ignorance, real as well as feigned, that the BLManiacs all seem to share. If

those who screamed their heads off were even aware that Jesus was born a hunded percent Jewish, one could even accuse them of anti-Semitism, which is, of course, not as bad as being actually anti-Christ because

anti-religion in general.

A Jesus who looks like each of us

If we tear down white Jesus, then, by extension,

we have to tear down all images of Jesus

by David Bonagura Jr.

July 13, 2020

“Tear them down.” So ranted a liberal activist recently about “the statues of the white European they claim is Jesus.” Depicting Jesus in this way, he continued, is “a form of white supremacy.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury agreed that “white Jesus” should be reconsidered. [Justin Welby is a spineless ninny and will never be anything but.]

Are they right? Are we wrong to depict Jesus as white, or as any race other than Judean or Syrian?

No. The reason lies in the mystery of the Incarnation, and, ironically, is confirmed by the tenets of identity politics that liberal activists espouse.

In the Incarnation ,the eternal Word entered history, whereby he willingly subjected himself to the limits of space and time. Like all other men, Jesus of Nazareth was of a particular ethnicity and genetic make-up.

With only one human parent, he must have born a striking resemblance to his virgin mother, of whom no portrait exists. Of Jesus himself, two mystical images survive: the one imprinted on Veronica’s veil, and the other on the burial shroud of Turin, though the latter’s presence remained undetected until the negative photographs in the 19th-century exposed the face of a Middle Eastern bearded man.

Neither cloth captures Jesus’s face as a modern photograph would; we have only indirect, glancing impressions, and they were not widely circulated for the first 1800 years of Christianity. After the apostles and first disciples died, Jesus’s appearance became a feast for the imagination.

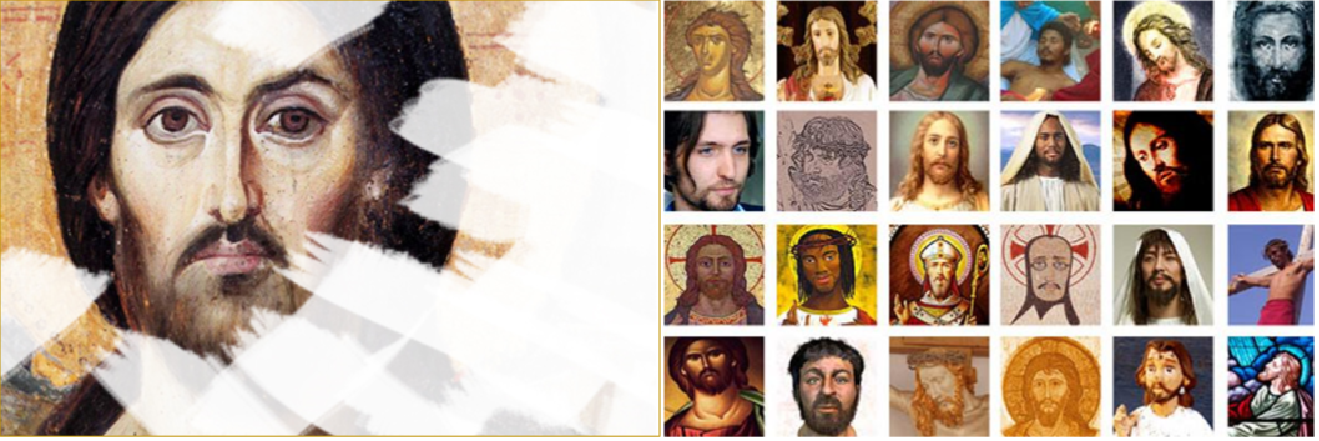

From the beginning, Jesus’s appearance in sacred art and icons depended on who painted him and where.

In St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula, the oldest icon of Jesus, painted in the 6th century, portrays a light-skinned Egyptian man.

Left, oldest known icon of Christ; top right, earliest depiction of Jesus in the Roman catacomb of St. Priscilla; bottom right., St. Catherine's monastery at the foot of Mt. Horeb in the Sinai Peninsula, 2 km south of the Biblical Mt Sinai, houses over 160 icons from the 5th and 6th

Left, oldest known icon of Christ; top right, earliest depiction of Jesus in the Roman catacomb of St. Priscilla; bottom right., St. Catherine's monastery at the foot of Mt. Horeb in the Sinai Peninsula, 2 km south of the Biblical Mt Sinai, houses over 160 icons from the 5th and 6th

centuries, as the monastery was untouched during the great Byzantine iconoclasm.

In Rome’s catacombs, we find the earliest depiction of Jesus as a Roman without a beard, especially in the famous Good Shepherd mosaic.

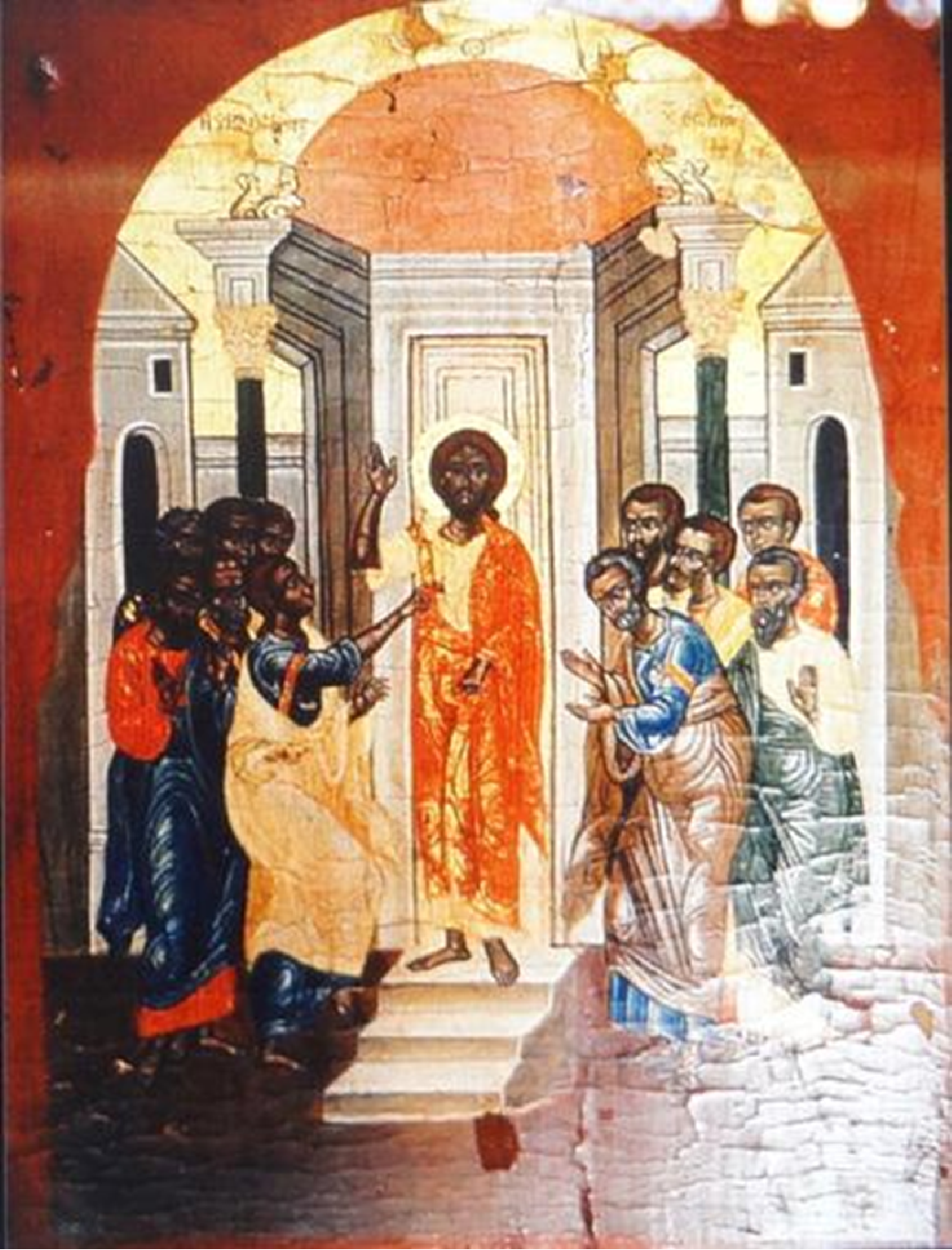

In Egypt, the Coptic Museum of Cairo houses an icon of Jesus flanked by his apostles; Jesus and the disciples to his right are black men, while the five to His left are brown.

As the gospel spread over time, we can find Jesus depicted differently in every land, from Chinese, as is found in the art of the Xishiku Cathedral in Beijing, to, yes, a white European. And this illustration itself is not monolithic: Jesus can be drawn as a western European or a Slavic European, depending on who is doing the painting.

What unites these varying depictions of Jesus across cultures and centuries is not a hatred of every race except one’s own. Quite the opposite.

In desiring ourselves to become more like him, we unwittingly imagine him like us — as our brother, which includes his physical resemblance to us.

Gaudium et Spes teaches that

“Christ, the final Adam, by the revelation of the mystery of the Father and His love, fully reveals man to man himself and makes his supreme calling clear” (no. 22).

n addition to revealing our supernatural destiny, Christ enables us to know ourselves better and to realize, by divine grace, our human potential in and through him. This includes accepting the vocation he has given us, as well as accepting our natural gifts and shortcomings. Our physical make-up — size, shape, health, heritage, and ethnicity — forms part of who we are and how we encounter Christ. With grace, we integrate all the aspects of ourselves into our singular personality, which is vivified by knowing that God has made us his own.

Race is an important part of our being. Polling data suggests that people are more apt to respond to advertisements and films if those portrayed are of the same race as the spectators. In other words, the motivation for modern cinematic casting and for depicting Jesus as a member of one’s own race is the same.

As our creator, God knows this better than we do. So, to name just one example, when the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared in 1531 to St. Juan Diego, a member of the Nahua people in Mexico, she spoke his Nahuatl language and appeared with brown skin, as she miraculously appears on his tilma that survives to this day.

Depicting Jesus as a member of one’s own race, then, is natural, not racist. Racism requires us to denigrate other races willingly in the false belief that they are inferior. Sadly, in history a few have convinced themselves that Jesus’S race was like their own, because he could not have been, they asserted, some “lesser” race. The reality of the Incarnation, again, immediately refutes such a facile and, frankly, stupid claim that need never be taken seriously.

On the other hand, today’s identity politics movement, in transforming race from part of a person’s life to the constitutive factor of one’s being, has chosen to perceive race only in terms of power; differing races, in this view, are perpetually at war with each other as oppressor and victim. With a mindset of perpetual warfare, such advocates can insinuate racial conflict where there is none. And there is none when one projects Jesus, in longing to imitate him, as an image of oneself, be he European, African, Asian, or of any other ancestry.

If we tear down white Jesus, then, by extension, we have to tear down all images of Jesus, because to do so would be to impale faith and deny the Incarnation. This would also inhibit our natural longing for God that is stamped into our human nature. In our limited horizons, we picture God as we are.

But God became man not so we could make him more like us, but so that we could become like him — ”conformed to the image of his Son,” as Paul puts it, “in order that he might be the first-born among many brethren”

(Rom 8:29) — who is perfectly just, perfectly mercifully, and loves all men and woman indiscriminately as his own.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 14/07/2020 14:32]