Last Testament

Last Testament

by Benedict XVI

with Peter Seewald

Bloomsbury, £16.99

The most revealing book yet on Benedict XVI

A new book-length interview portrays a prophet of our age

by Luke Coppen

Thursday, 3 Nov 2016

The drill instructor surveyed the new recruits. He was expected to turn this pathetic rabble into an efficient fighting force for the Führer.

“Who’s holding out for longest,” he bellowed, “you or me?” There was an uncomfortable silence. Then the smallest soldier in the line – a weedy and bookish figure – stepped forward and said: “Us!”

That defiant young man became arguably the most influential Christian theologian of our age and served for eight years as the spiritual leader of a billion souls. He has never lost what he calls “the desire for contradiction”: a willingness to rebel against the dictates of the age, alone if necessary. Joseph Ratzinger

contra mundum.

The drill instructor anecdote is just one of many astoundingly fresh and revealing stories in

Last Testament. The book is based on interviews with Benedict XVI conducted before and after his resignation by German journalist Peter Seewald. This is therefore a historic document in which for the first time in centuries – perhaps ever

[No perhaps: EVER, period] – a retired pope evaluates both his own pontificate and his successor’s.

When the book was first announced it didn’t sound all that promising. Seewald and Benedict XVI had already collaborated on three book-length interviews:

Salt of the Earth,

God and the World and

Light of the World. As Benedict’s personal secretary, Archbishop Georg Gänswein, put it at the new work’s launch: “These questions were in a field that seemed to be already harvested.” Yet somehow Seewald has gathered in perhaps the finest harvest yet.

For more than a decade I have read everything I can about Benedict XVI, but I was amazed by the revelations in this new book. I never knew, for example, that Benedict’s mother was illegitimate, that he held his first meetings as Vatican doctrinal chief in Latin (his Italian was shaky), and that he has long been totally blind in his left eye (a fact that surprised even Gänswein).

Seewald teases out some wonderful vignettes. Benedict recalls going to a party at Ernst Bloch’s house with “an Arab” who offered the Marxist philosopher his first ever drag on a hookah (“He couldn’t handle it,” he comments).

He also describes how he took a choppy boat trip to Capri while serving as a theological adviser to Cardinal Frings at the Second Vatican Council. “We all vomited, even the cardinal,” he says, clearly cherishing the memory.

But Seewald is no mere biographer. He has a larger agenda: to bury the image of Benedict XVI as an aloof reactionary whose reign ended in dismal failure and replace it with one in which the German pope is the true prophet of our age.

The “much-maligned Panzerkardinal ”, he writes in the foreword, is actually

“one of the most significant popes ever, the modern world’s Doctor of the Church”. As an admirer of Benedict, I agree. But Seewald’s revisionism occasionally goes too far. He argues, for instance, that at the Vatican between 2005 and 2013 “liturgical extravagance was reduced” – which doesn’t quite ring true.

[I think the word is 'abuse' not 'extravagance' - abuse of the Novus Ordo was not perhaps not exactly reduced, but certainly, it was deterred from worsening o becoming more widespread.]

The book also unleashes heavy weaponry in what we might call “the Ratzinger wars” in Germany: a decades-long controversy about the direction of one of the world’s wealthiest and most influential local churches.

Benedict deplores his homeland’s “established and well-paid Catholicism” and says, wistfully, that “certain people in Germany have always tried to bring me down”. He says that they latched on to “the stupid Williamson case” – when he lifted the excommunication of the English SSPX bishop without realising he was a Holocaust denier – and attacked him right up to his resignation.

Seewald pushes Benedict to deny Hans Küng’s theory that he was a progressive theologian until student protests in 1968 turned him into an embittered conservative who pulled strings to silence Küng. Whether this will be enough to displace the Küng narrative, echoed and amplified for years by the global media, remains to be seen.

Benedict’s own account of his pontificate is touchingly modest. He says it was “unreasonable” that he should have been elected at 78 and that he took the name Benedict because “I could not be a John Paul III … I had a different sort of charisma, or rather

a non-charisma”.

Charisma aside, he served the Church to the best of his considerable abilities, while being undermined by both bungling colleagues and sworn enemies. Now living in a monastic setting, he says that he looks forward to heaven, where he will stand “before God, and before the saints, and before friends and those who weren’t friends”.

The book’s title, Last Testament, is one rendering of the German

Letzte Gespräche. Another [

the literal one] might be “Latest Conversations”. While the book does have a valedictory feel, you can’t help thinking, as you finish it, that

Benedict XVI has a lot more left to say to the world.

[All these past 44 months - what he might have said to the world in place of the undisciplined yet clearly anti-Catholic stream of consciousness we have been getting by way of 'papal' communications!]

Call it Bavarian family values and Bavarian Catholic awareness of important family anniversaries, but it is quite surprising to find an article on Joseph and Georg Ratzinger’s older sister Maria in Bavaria’s largest newspaper on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of her death. Say a special prayer for her eternal repose and comfort to the brothers she left behind, especially Joseph to whom she devoted her service as confidante, secretary and housekeeper from the moment he started his academic career to the day she died on November 2, 1991.

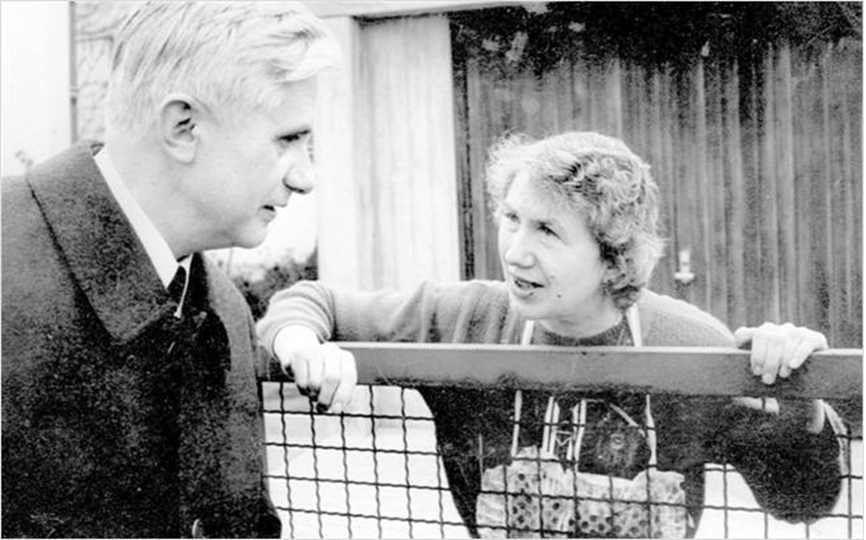

Prof. Fr. Ratzinger speaks to his sister across the back gate of their home in Pentling...

The Pope’s sister

Prof. Fr. Ratzinger speaks to his sister across the back gate of their home in Pentling...

The Pope’s sister

She served her brother Joseph for many years but little is known of Maria Ratzinger.

A look into the life of a woman who, others thought, thereby ‘sacrificed’ herself

By Andreas Glas

Translated by VB for benoit-et-moi/2016.fr from

October 28, 2016

There is a photograph from the 1980s which says a lot about Maria Ratzinger. In the background is a well-decorated Christmas tree. In front of the tree are the Ratzinger siblings: her brothers, both in priest’s cassock, standing straight as candles. Between them, Maria – head hunched on her shoulders and eyes cast down, her hands holding on to her brothers. One sees a woman so shy that she practically disappears between them, a woman who chooses to stay in the shadow of her brothers instead of living her own life. But does that photo reflect the truth?

Pentling, a suburb of Regensburg, at the end of October 2016. The autumn sun is still quite warm, the cemetery is silent, and one can only hear the sound of one’s shoes walking over its gravel paths. Twenty-five years ago, Maria Ratzinger too was here to prepare the gravesite of her parents for All Saints Day. But on that October 30, returning home from the cemetery, she suffered a coronary infarct, and two days later, on Soul’s Day, she died at a hospital in Regensburg. She was 69.

The obituary that Georg and Joseph Ratzinger published in the SZ specifically mentioned that Maria had consecrated most of her life to her younger brother Joseph [who would become Pope]. “For 34 years,” one reads, “she served Joseph in all the stages of his life work with tireless devotion and with great kindness and humility”.

So Maria Ratzinger, servant. Was she anything else?

It’s only a few minutes walk from the cemetery to Bergstrasse, the quiet street where Maria lived with her brother Joseph until the latter went to Rome in 1992 to be Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and Maria went with him.

[ Actually, she left Pentling to be with him when he was named Archbishop of Munich in 1977.]

The house in Pentling is now a museum and study center, but it still needs ‘housekeeping’ – and it has been Therese Hofbauer, the Ratzingers’ next-door neighbor, who has done this for 34 years.

On this October afternoon,Therese, now in her 70s, is seated at her kitchen table. In the nearby Herrgottswinkel [‘the Lord’s corner], there is a Crucifix carved from wood and a framed photograph of the future Benedict XVI when he was ‘just a neighbor’. Many journalists have been seated at Therese’s kitchen table, especially in 2005, just after Joseph Ratzinger was elected Pope.

Newsmen came from all over the world, and also besieged Georg Ratzinger, who lives in the Regensburg city center near the Cathedral. Up until then, media had been more interested in Georg Ratzinger who, as longtime choir director of the Regensburg Cathedral’ boys’ choir, was a public personage in his own right.

What about their sister? Therese says, ”I often spoke to newsmen also about Maria, but it seemed she was of no interest to them”.

Born in 1921, Maria was the oldest of the Ratzinger siblings. She wanted to be a teacher, but college education was expensive for the family, and the parents chose to invest what they had in the two brothers who wanted to be priests. At the time, that was a normal choice for parents to make.

So Maria attended the Haustöchterschule in Au am Inn, a school run by Franciscan sisters to train young girls in ‘home economics’ and other useful skills. After the war, she found work as a secretary in a Munich law firm. When, in the summer of 1959, Joseph was named professor of dogmatic theology at the University of Bonn, Maria decided to accompany him – never leaving his side again until she died, keeping house for him and much more.

Was this a sacrifice of herself? “No,” says Therese Hofbauer. “It would be a great mistake to say that. Maria was a woman of great personal freedom”.

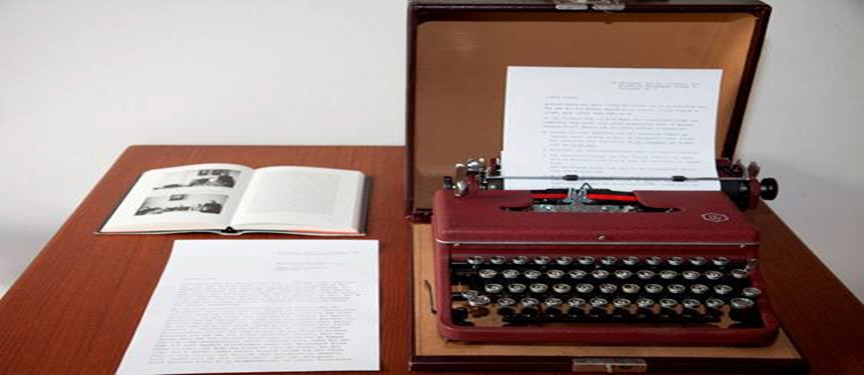

To understand what she means, one simply has to take a look at Maria’s bedroom in Pentling, as the Foundation that now owns the property has kept the rooms of Joseph and Maria as they were at the time they lived there.

Maria’s room has a bed, shelves full of books, a desk and a typewriter on it. The books appeared to have been read by her in order to better understand her brother’s work as a theologian, and the typewriter was the last one she used to type his lectures and manuscripts because Joseph never learned to type.

Therese says Maria was not just her brother’s housekeeper and cook – but she also served as his first editorial reader [in publishing houses, readers have the task of ‘screening’ manuscripts, as it were]. Does that mean she had any influence on what he wrote? “In any case, they discussed these manuscripts between them,” Therese says.

[Cardinal Ratzinger often said that he always ‘tried out’ his lectures and homilies on her first, like a sounding board.]

Far from being a servant or ‘sacrificing herself’ for her brother, Therese Hofbauer says, Maria felt that as a secretary for a lawyer’s firm, she was intellectually ‘under-employed’.

So this reading of Maria Ratzinger indicates that the woman who was unable to pursue higher education transformed herself consciously into a scientific assistant of her brother, the university professor. The woman whom critics today would think unemancipated was someone who was not content to simply be a housekepper.

But why did she never marry? “I do not know,” says Therese. “We never spoke about this. But she was very content with her life”.

Instead of being bound to a husband, her own children and a permanent home, she lived with her brother in Bonn, Muenster, Tuebingen, Regensburg, Munich and finally Rome.

She was surprisingly progressive in the way she led her life, Therese notes, but people simply did not know her. “In considering her as nothing more than an appendage of her brother, people did not know what she had in her”.

“As their neighbor, I know that Maria was never just the ‘servant’ of her brother”, she adds. “For instance, it was always he who did the dirty jobs like getting rid of the garbage. And she had her rules – like, he could never enter the house with dirty shoes.” .

[ [One can imagine all the house rules an older sister could have for a younger brother when they had no house help.]

Indeed, Maria was always the Big Sister, five years older than Joseph. And she could be ‘very strict’ with him, notes Therese.

On the other hand, there is a wealth of proof that Maria realized her own wishes for herself by sharing her brother’s life. After having lived in Rome a number of years, she told a nun in a convent in Munich that she was happy to be carrying out the task their mother had entrusted to her, namely, to take care of her two brothers, especially Joseph”. This is recounted in a biography of Benedict XVI by Johann Nussbaum.

More than any other biographer of the emeritus pope, Nussbaum – a resident of Rimsting

[ one of the ancestral villages that their mother’s family lived in] – was interested in Maria Ratzinger, describing her as her brother Joseph’s ‘silent companion’. She was with him at practically all the public and social events attended by him.

Nussbaum is surprised that there was very little interest in Maria Ratzinger: “In order to get a full picture of the Ratzinger family, one cannot simply ignore her”. But he does not believe she influenced his work at all. “Of course, she did more than just type his texts. She also corrected errors of form, but never interfered with the content”.

Later, when they came to Rome, she learned to speak Italian “because that was indispensable in order to feel at home in Rome”, Nussbaum says in his book.

But others say that she was never really at ease in the masculine world of the Vatican. Only Joseph Ratzinger can tell us if his sister was happy in Rome. Maybe Georg Ratzinger also could, but we were unable to reach him for comment because he spent much of the summer at the Vatican with his brother.

Clearly, the sudden death of Maria profoundly affected the Ratzinger brothers. Those who were at her funeral services said Joseph Ratzinger cried openly. Every year after her death, he visited the family gravesite in Pentling, says Therese Hofbauer. This stopped only when he was elected pope.

He came, perhaps for the last time, during his state visit to Bavaria in 2006. With Georg standing nesrby, he knelt in prayer before the resting place of their parents and sister.

“His final minutes before the tomb of his parents” was the headline of one of the local newspapers at the time, which accompanied the photographs with a history of the Ratzinger family, in which sister Maria was only mentioned in passing.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 06/11/2016 04:16]