THE POPE IN CONCESIO

THE POPE IN CONCESIO

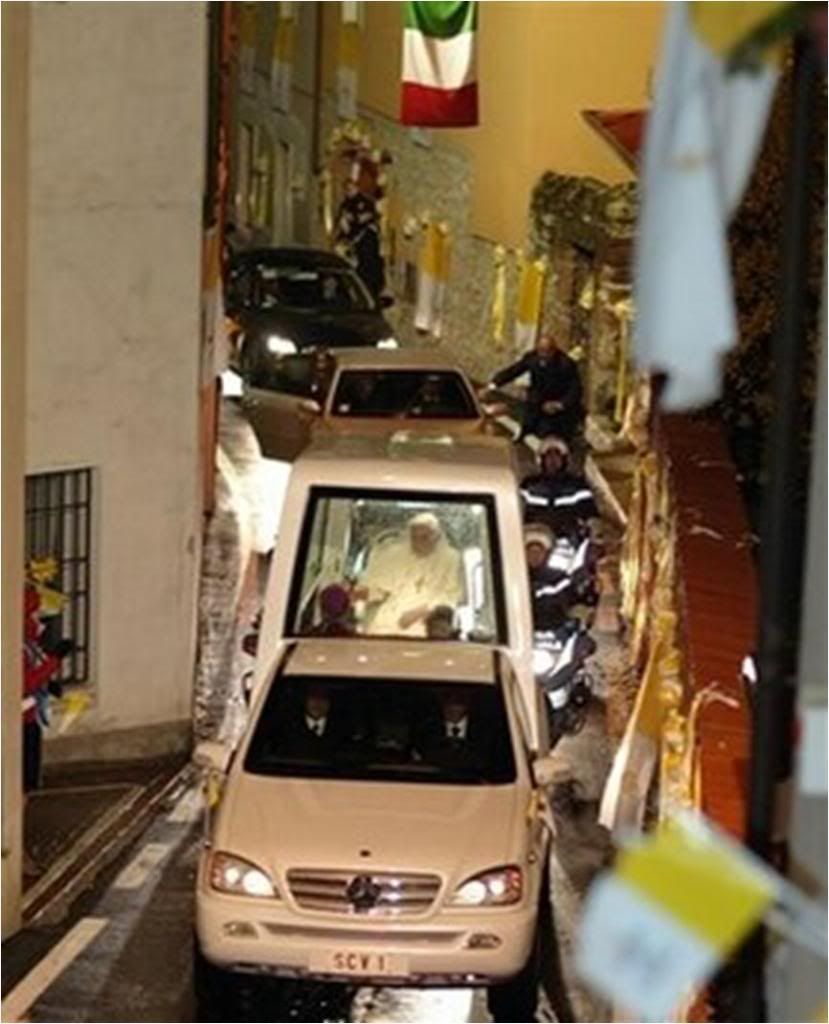

The Holy Father travelled by Popemobile along the 8 kilometers that separates the town of Concesio from the center of Brescia, and arrived in Paul VI's hometown to visit Montini's birthplace and the adjoining new headquarters of the Istituto Paolo VI which the Pope inaugurated.

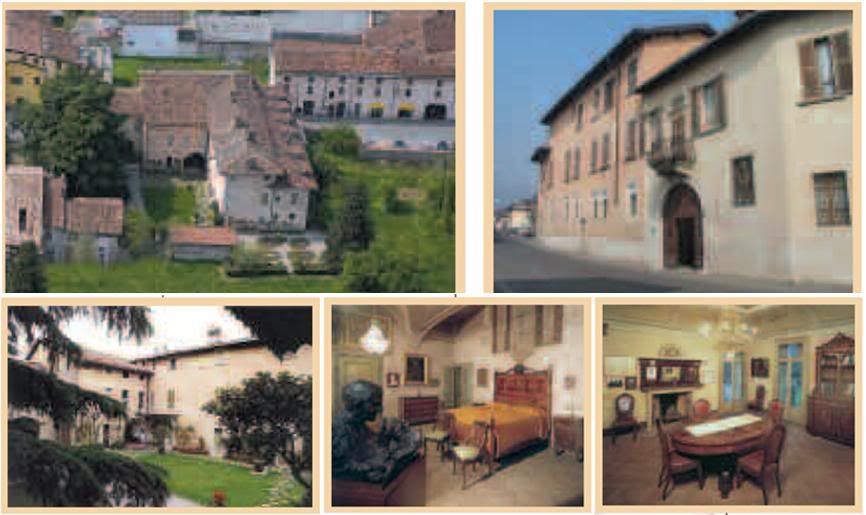

Photo shows from top left, clockwise, an aerial view of the Montini property; the street entrance to the house; the dining room; the room where the future Pope was born; and the house entrance seen from the inner courtyard. The new Istituto Paolo VI headquarters was built on the large expanse of meadow to the rear of the property (it would be the foreground of the top left photo).

Following background information on the Montini house and the new Istituto Paolo VI headquarters is translated from:

Photo shows from top left, clockwise, an aerial view of the Montini property; the street entrance to the house; the dining room; the room where the future Pope was born; and the house entrance seen from the inner courtyard. The new Istituto Paolo VI headquarters was built on the large expanse of meadow to the rear of the property (it would be the foreground of the top left photo).

Following background information on the Montini house and the new Istituto Paolo VI headquarters is translated from:

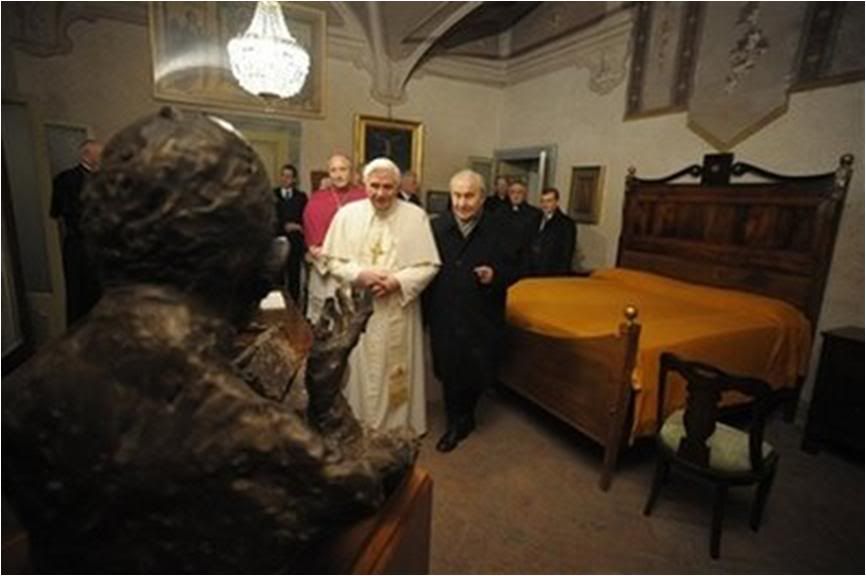

The house where Paul VI was born is a 17th-century structure built on the foundations of a 15th-century building. It was acquired by the Montini family from the Counts of Lodrone in 1830, and seerved as the country home for the parents of teh future Pope. It retains all its 17th century features, including frescoed ceilings, tiled floors, and an old-fashioned kitchen that features a large stone tub.

It is furnished the way it was around the turn of the century (19th to the 20th) when Giovanni Battista Montini was born. The room where he was born is kept as it was then.

The property was passed on to the Istituto Paolo VI by the remaining Montini heir, Vittorio.

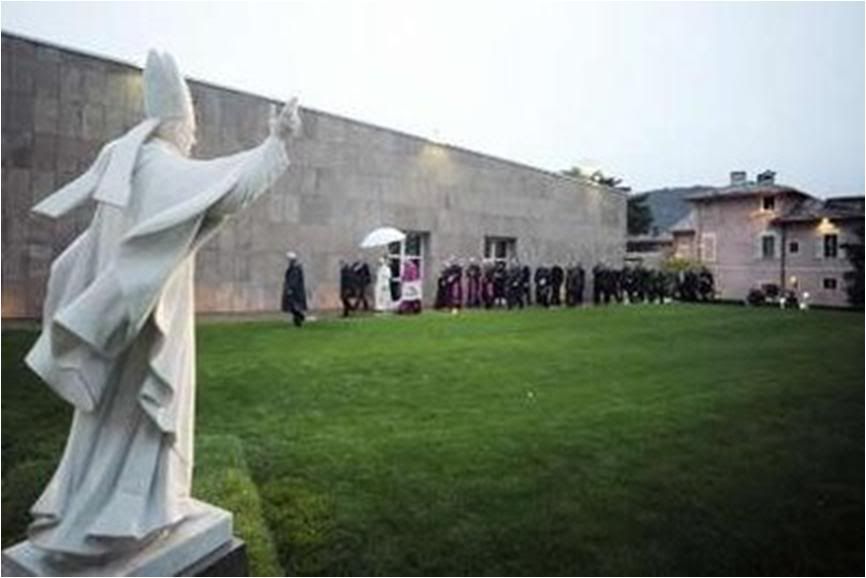

From the house, the Holy Father and his party walked towards the Institute headquarters in the 'rear' of the Montini property.

From the house, the Holy Father and his party walked towards the Institute headquarters in the 'rear' of the Montini property.

The new headquarters of the Istituto Paolo VI is a three-story modern building of 2500 square meters, which houses a museum of contemporary sacred art, a library with 30,000 volumes, an archive of 500,000 documents, of which 50,000 are directly on Paul VI, as well as an auditorium that holds 250 people (where the ceremony with the Pope was held today).

For 30 years since it was established in 1979, the Institute worked out of the Centro Pastorale Paolo VI in Brescia. The new headquarters is located in the area behind the Montini country home where the future Pope was born.

The property had 3,500 square meters of meadow, part of which is now occupied by the building, with a still considerable area of lawn left. The modern 3-story building is built with stone that matches the hilly pre-Alpine landscape of Concesio.

The Institute's museum of art now has some 250 paintings on display, including works by Picasso, Chagall, Manzù, De Chirico, Sassu, although all in all, the collection already owns some 7000 works.

Paul VI had a great passion for the arts and started the Vatican's own Museum of Contemporary Religious Art.

Giuseppe Camadini, a Brescian lawyer adn entrepreneur, is president of the Institute. At a news conference last week, he said:

"The Institute is an international center for study and documentation, originally sponsored by the Opere per l'Educazione Cristiana of Brescia and founded on April 10, 1979. The initiative has a civic as well as religious value."

He said that primarily, it offers Italian and foreign scholars the possibility of finding the tools and research materials they may need to conduct studies on the life and work of Paul VI. The archive contains published and unpublished documentation on the late Pope. The library has focused on books concerning the history and culture of the period during which the Pope lived. The Institute has published 60 monographs on Paul VI as well as a semestral newsletter of which there are now 57 issues.

The Paul VI International Prize was called the Catholic Nobel Prize by John Paul II, and given to persons and/or institutions who have made outstanding contributions to religious culture and education.

The sixth award went this year to the publishers of Sources Chretiennes, a French book series republishing the texts of early Christian writers. It has published over 350 volumes since it was started in 1947 by the French theologians Henri de Lubac and Jean Danielou. Its work has contributed to the resurgence of interest in the Fathers of the Church in the late 20th century.

Previous winners of the Prize were Hans Urs von Balthasar, in 1984; to French composer Olivier Messieaen in 1988; Oscar Cullmann (1902-1999), outsstanding Lutheran theologian who took part in the Vatican II and was a mainstay of the ecumenical movement just before he died in 1999; Canadian Jean Vanier, a retired naval general who founded L'Arche, an international organization which creates communities where people with developmental disabilities and those who assist them share life together, in 1997; and French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, in 2002.

AT THE INSTITUTE

The following pictures are my videocaps from the CTV feed, which I can only get through the Vatican Radio page. A distortion in the video results in a slight vertical elongation of the images.

AT THE INSTITUTE

The following pictures are my videocaps from the CTV feed, which I can only get through the Vatican Radio page. A distortion in the video results in a slight vertical elongation of the images.

Below right, the Pope gives the Paul VI International Prize to Bernard Menier, director of Sources Chtretiennes.

Below right, the Pope gives the Paul VI International Prize to Bernard Menier, director of Sources Chtretiennes.

'The encounter with Christ

'The encounter with Christ

is a liberating educational experience'

Here is a translation of the Pope's discourse:

Eminent Cardinals,

Venerated Brother Bishops and Priests,

Dear friends:

I thank you all from the heart for having invited me to inaugurate the new heacdquarters of the institute dedicated to Paul VI, built next to the home where he was born.

I greet each of you affectionately, starting with the cardinals, bishops, authorities and other personages present. I address a special greeting to your president, Giuseppe Camadini, thankful for the kind words which he addressed to me, and for illustrating the origins, purpose and activities of the Institute.

It is my pleasure to take part in the solemn ceremony of awarding the Paul VI International Prize, given this year to the French book series Sources Chretiennes. A choice made in the field of education, which is meant to highlight - as it has been well underscored - the profuse activity of this historic book series, started in 1942 by Henri de Lubac and Jean Danielou, among others, for a renewed discovery of ancient and medieval Christian sources. And I thank the series editor Bernard Meunier for the greeting he addressed to me.

I take this propitious occasion to encourage you, dear friends, to increasingly bring to light the personality and doctrine of this great Pontiff, not so much from the hagiographic and celebratory aspect, but rather - and this has been rightly noted - from the aspect of scientific research, in order to offer a contribution to the knowledge of truth and understanding of the history of the Church and the Popes of the 20th century.

To the degree that he is better known, the Servant of God Paul VI is better appreciated and more loved. A bond of affection and devotion unites me to this great Pope, starting from the years of the Second Vatican Council. And how can I forget that in 1977, it was Paul VI who entrusted me with the pastoral care of the Diocese of Munich and then made me a Cardinal? I feel I owe this great Pontiff so much gratitude for the esteem that he showed me on various occasions.

I would love to speak in depth, in this headquarters, of the different aspects of his personality. But I will limit my considerations now to one single aspect of his teaching, which I think to be of great relevance and in tune with the motivation for this year's Prize, which is educational capability.

We live in a time in which we note a true educational emergency. To form the young generations, on whom the future depend.s has never been easy, but in our time, it seems to have become even more complicated. And this is well known to parents, teachers, priests and those who have direct educational responsibilities.

An atmosphere, a mentality, and a form of culture iare becoming widespread that result in casting doubt on the value of the person, on the meaning of truth and of goodness, and ultimately, on the goodness of life itself.

And yet one also notes strongly a similarly widespread thirst for certainties and for values. It is therefore necessary to transmit to future generations something valid - solid rules of behavior, high objectives towards which to decisively orient their existence.

The demand is growing for an education that is capable of taking responsibility for the expectations of young people: an education that must be above all else, testimony, and for the Christian educator, a testimonial of faith.

In this respect, what comes to my mind is this incisive statement by Giovanni Battista Montini, written in 1931: "i would like my life to be a testimonial to truth... I mean by testimonial the custody, the search for and the profession of the truth" (Spiritus veritatis, in Colloqui religiosi, Brescia 1981, p. 81).

Such a witness, Montini noted in 1933, is made impelling by the observation that "in the profane field, men of thought - even and perhaps especially in Italy - think nothing of Christ. He is unknown, forgotten, absent, in a great part of contempoary culture"

(Introduzione allo studio di Cristo, Roma 1933, p. 23).

Montini the educator - as student and priest, Bishop and Pope - was always aware of the need for a well-qualified Christian presence in the world of culture, art and social aitivity, a presence rooted in the truth of Christ that is at the same time, attentive to man and his vital needs.

That is why attention to the educational problem and the formation of youth was such a constant in the thought and actions of Montini, an attention that also came from his family environment.

He was born to a family belonging to the Brescian Catholicism of that time, which was committed and fervent in works, and he grew up with the example of his father Giorgio, who was a protagonist in important battles to affirm freedom of education for Catholics.

In one of his earliest writings dedicated to Italian schools, Giovanni Battista Montini observed: "We do not ask more than a bit of freedom to educate as we wish the young people who come to Christianity attracted by the beauty of its faith and traditions"

(Per la nostra scuola [For our school], a book by Prof. Gentile, in Scritti giovanili [Youthful Writings], Brescia 1979, p. 73).

Montini was a priest of great faith and wide culture, a leader of souls, an acute inquirer into the 'drama of human existence'. Generations of young university students found in him, when he was spiritual director of FUCI [federation of Italian Catholic universities], a point of reference, a former of consciences who was able to arouse enthusiasm, to call them to their mission to be witnesses at every moment of life in order to show off the beauty of the Christian experience.

When they heard him speak, his students said of him, they perceived the interior fire that animated his words, in contrast to his frail appearance.

One of the bases for the educational offerings by the university circles that he led at FUCI consisted in orienting the personality of the young people towards spiritual unity - "No separate compartments in the soul," he said, "with culture on one side, and faith on the other; or school on one hand, and Church on the other. Doctrine, like faith, is one" (Idee=Forze (Ideas=Power] in Studium 24 [1928], p. 343).

In other words, for Montini, full harmony and the integration of the cultural and religious dimensions of formation were essential, with particular emphasis on knowledge of Christian doctrine and the practical developments of life.

Because of this, from the start of his activities in the Roman circle of FUCI, he promoted among university students, along with serious spiritual and intellectual commitment, charitable initiatives to serve the poor, through the conference of St. Vincent [de Paul].

He never separated what he would later call 'intellectual charity' from social presence in taking on responsibility for the needs of the neediest. This is how the students were educated to find continuity between the rigorous duty to study and their concrete tasks among the shanty dwellers.

"We believe," he wrote, "that the Catholic is not one tormented by a hundred thousand problems, even if these may be spiritual in nature. No! The Catholic is he who has the fecundity of certainty. Thus, faithful to his faith, he can look at the world not as an abyss of perdition but as field of harvests" (La distanza dal mondo, in Azione Fucina, 10 Feb 1929, p. 1).

Giovanni Battista Montini insisted that the formation of young people must make them capable of relating with modernity - a difficult and often critical relationship, but always constructive and dialogic.

He underlined some negative characteristics of modern culture, both in the field of knowledge as well as in practice - such as subjectivism, individualism, and the unlimited assertion of the subject. At the same time, he thought dialog was necessary but must always start from solid doctrinal formation, whose unifying principle is faith in Christ, therefore, a mature Christian 'consciousness' able to confront everything without falling into the fashion of the time.

As Pontiff, he said to the Rectors and Presidents of the universities of the Society of Jesus, that "doctrinal and moral mimetism is certainly not in conformity with the spirit of the Gospel".

"Moreover," he continued, "those who do not share the position of the Church ask us for extreme clarity in our positions in order to establish a constructive and loyal dialog".

That is why cultural pluralism and respect "should never let the Christian lose sight of his duty to serve the truth in charity, to follow the truth of Christ which, alone, gives true freedom" (cfr. Insegnamenti xiii, [1975], 817).

For Papa Montini, the young person must be educated to evaluate the environment in which he lives and works, to consider himself as a person and not a number in the crowd: in a word, he must be helped to have 'strong thinking' capable of 'strong action', while avoiding the danger that he may sometimes risk of placing action before thought, and turning experience into the source of truth.

He said in this regard: "Action cannot be a light to itself. If one does not wish to bend man to think as he acts, he must be educated to act as he thinks. Even in the Christian world, where love, carita, has supreme and decisive importance, one cannot do without the light of truth, which presents love with its ends and its reasons" (Insegnamenti II [Teachings, Vol II], 1964, p. 194).

Dear friends, the years of FUCI, which were difficult because of the political context in Italy, but exciting for the young people who recognized in the Servant of God a leader and an educator, left a lasting mark on the personality of Paul VI.

As Archbishop of Milan and then Successor of the Apostle Peter, his yearning and his concern for the subject of education never waned. This is attested to by his numerous interventions dedicated to the new generations, in tempestuous and tormented times, as in 1968.

With courage, he showed the way to an encounter with Christ as a liberating educational experience and the only true response to the desires and aspirations of young people who had become victims of ideology.

"You, the young people of today," he reiterated, "are sometimes captivated by a conformism that can become habitual, by a conformism that unconsciously bends your freedom to the automatic domination of external currents of thought, of opinion, of sentiment, of action, of fashion: and then, caught up in a gregariousness that gives you the sense of being strong, you become rebels as a group, en masse, often without knowing why".

"But then, if you acquire a consciousness of Christ, and you adhere to him... you will become free interiorly... you will know why and for whom you live... And at the same time, like something marvelous, you will feel born in you the science of friendship, of sociality, of love. And you will not be isolated" (Insegnamenti vi [Teachings VI, [1968], pp 117-118).

Paul VI called himself 'an old fieind of young people': he could recognize and share their torment in the debate between the will to life, the need for certainty, and the yearning for love, on the one hand against their sense of disorientation, the temptation of skepticism, the experience of disappointment, on the other.

He had learned to understand their spirit and reminded them that the agnostic indifference of current thought, pessimistic criticism, the materialistic ideology of social progress, do not suffice for the spirit, which is open to other horizons of truth and life (cfr. Insegnamenti xii [Teachings, XII, [1974], p. 642).

Today, like then, an unavoidable question emerges for the new generations, a demand for meaning, a search for authentic human relationships. Paul VI said: "Contemporary man will more gladly listen to witnesses than to teachers, or if he listens to teachers, he does so only because they are witnesses first" Insegnamenti xiii [Teachings XIII], 1975, pp 1458-1459).

My venerated Predecessor was a teacher of life and a courageous witness of hope, who was not always understood, and indeed many times was opposed and isolated by the dominant cultural movements in his time.

But as solidly as he was physically fragile, he led the Church without hesitations. He never lost his trust in young people, renewing to them, and not just to them, the invitation to trust in Christ and to follow him on the road of the Gospel.

Dear friends, once more, thanks for giving me the opportunity to breathe in, here, in his hometown and in these placed full of memories of his family and his childhood, the atmosphere in which the Servant of God Paul VI was formed, the Pope of the Second Vatican Council and of the immediate post-Conciliar years.

Here, everything speaks of the richness of his personality and his vast doctrine. Here, there are significant memories of other pastors and protagonists of the history of the Church in the past century, as for instance, Cardinal Bevilacqua, Bishop Carlo Manziana, Mons. Pasquale Macchi, his trusted private secretary, and Fr. Paolo Caresana.

I hope from the heart that the love of this Pope for young people, his constant encouragement to entrust themselves to Christ - an invitation taken up by John Paul II, and which I, too, wished to renew at the start of my Pontificate - may be perceived by the new generations.

For this, I assure my own prayers, as I bless all of you who are present, your famlies, your work, and the initiatives of the Istituto Paolo VI.

After the program, the Holy Father signed the Institute's Guest Book and was given a brief tour of the new building, inclduing its museum of contemporary sacred art.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 10/11/2009 18:33]