I just saw it today, but it gets my vote so far for the most perceptive and original reaction to the February 11 shocker. Barber is the author of a book on The Early Fathers of the Church, so he knows his material...

Did Benedict XVI take a page

I just saw it today, but it gets my vote so far for the most perceptive and original reaction to the February 11 shocker. Barber is the author of a book on The Early Fathers of the Church, so he knows his material...

Did Benedict XVI take a page

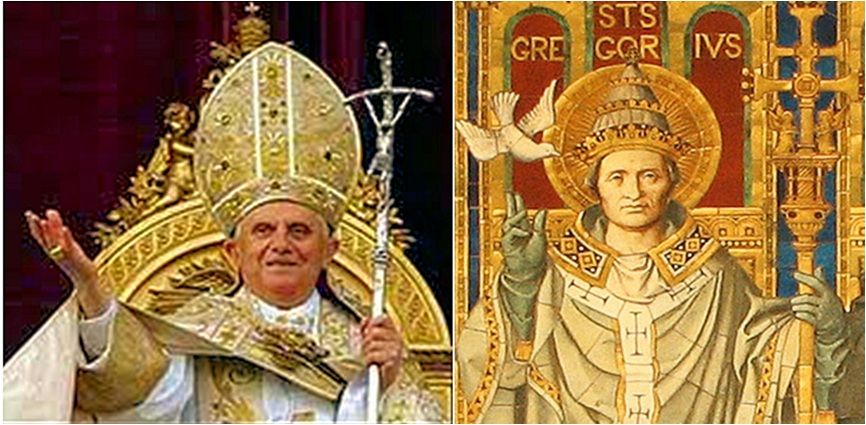

from Gregory the Great?

by Michael Barber

February 11, 2013

So why did Pope Benedict "renounce" his office? (I prefer "retire", but "renounce" is the most literal translation of the Latin text of his declaration).

Let me make a suggestion. Could it be that Benedict, who is well known for his encyclopedic knowledge of the Church Fathers, is taking a page not simply from Gregory XII, the last Pope to resign (1415), but also from Gregory the Great (540-604)? I have yet to see anyone point this out, but consider the following.

Gregory the Great wrote what is considered the classic treatment on the spiritual formation of pastors,

The Book of Pastoral Rule. Benedict clearly recognizes the importance of this work.

During the series of Wednesday audiences Benedict devoted to the early Church Fathers, he had the following to say about Gregory's Pastoral Rule:

Probably the most systematic text of Gregory the Great is the Pastoral Rule, written in the first years of his Pontificate. In it Gregory proposed to treat the figure of the ideal Bishop, the teacher and guide of his flock...

Taking up again a favourite theme, he affirmed that the Bishop is above all the "preacher" par excellence; for this reason he must be above all an example for others, so that his behaviour may be a point of reference for all...

Nevertheless, the great Pontiff insisted on the Pastor's duty to recognize daily his own unworthiness in the eyes of the Supreme Judge, so that pride did not negate the good accomplished.

For this the final chapter of the Rule is dedicated to humility: "When one is pleased to have achieved many virtues, it is well to reflect on one's own inadequacies and to humble oneself: instead of considering the good accomplished, it is necessary to consider what was neglected".

All these precious indications demonstrate the lofty concept that St Gregory had for the care of souls, which he defined as the "ars artium", the art of arts. The Rule had such great, and the rather rare, good fortune to have been quickly translated into Greek and Anglo-Saxon. (General Audience, Wednesday, 4 June 2008).

Now check out what Gregory says about the need for the "ideal bishop" to be free from the frailties of the body:

That man, therefore, ought by all means to be drawn with cords to be an example of good living who already lives spiritually, dying to all passions of the flesh; who disregards worldly prosperity; who is afraid of no adversity; who desires only inward wealth; whose intention the body, in good accord with it, thwarts not at all by its frailness, nor the spirit greatly by its disdain: one who is not led to covet the things of others, but gives freely of his own. . ." (Gregory the Great, The Book of Pastoral Rule, 1.10 (cited from NPNF2 vol. 12, p. 7).

It is hard to read Benedict's statement today and not think of Gregory the Great's advice:

In today's world, subject to so many rapid changes and shaken by questions of deep relevance for the life of faith, in order to govern the bark of Saint Peter and proclaim the Gospel, both strength of mind and body are necessary, strength which in the last few months, has deteriorated in me to the extent that I have had to recognize my incapacity to adequately fulfill the ministry entrusted to me".

Gregory the Great became Pope in 590 when he was 50 years old and died 14 years later. I have not found out what he died of, but his earliest biographer said he "suffered almost continually from indigestion and, at intervals, from attacks of slow fever, while for the last half of his pontificate he was a martyr to gout".

In any case, gout and chronic indigestion in his early 60s clearly did not incapacitate Gregory to be Pope, and cannot be compared to the accelerating physical debilitation of advanced age that has overtaken Benedict XVI at 86... The earliest point of comparison made between Gregory the Great and Benedict the Sublime (if I may be permitted to coin a phrase) was that Gregory's writings "were more prolific than those of any of his predecessors as Pope". Read more about the great Pope in the Catholic Encyclopedia

www.newadvent.org/cathen/06780a.htm

P.S. I beg pardon... but it turns out at least someone else wrote about the Gregory-Benedict connection on that fateful February 11, and in a larger context... The writer is President and Fellow of the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in Merrimack, New Hampshire...

The reason Benedict resigned

by William Fahey

February 11, 2013

The Catholic world is largely shocked by the publication of Pope Benedict XVI’s letter of resignation this morning. The secular world assumes the worst —no, it desires the worst, and by insinuation worms doubts into the minds of even the faithful.

The secular world will tear through the brief letter and fixate upon the line about a “world, subject to so many rapid changes and shaken by questions of deep relevance for the life of faith.” It will weave from these deconstructed words an existential tale of despair, scandal, and an authority which realizes it is no longer in touch with reality.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Benedict’s resignation is utterly consistent with his character. It is traditional — he brings from our history and our law a fact and feature of the Papal Office: one can and — under certain circumstance — should put aside that office.

His resignation demonstrates once again the firm mark of a father and a teacher. A father knows that his role is to provide example, instruction, and discipline, and ultimately put himself aside for the good of his own.

The Petrine ministry is not exercised for a man, or for bishops and priests, or even for Catholics alone. It is a ministry exercised for all those seeking God and for all those towards whom God’s mercy is extended. It is a demanding office.

As with every text published by Benedict, this letter of resignation has no imbalance, flab, impression, or vagueness. Not a word goes astray. It is shot through with paternal love and professorial clarity.

An honest reading of this document can only lead to profound gratitude and sympathy for a suffering father who must understand each act and decision he makes as having “great importance for the life the Church.”

No one could doubt that this Holy Father has meditated profoundly, and I expect repeatedly, on The Pastoral Rule of St. Gregory the Great — that sixth-century handbook for those who hold the highest spiritual authority, what Benedict and others have called the

ars artium (“the art of arts”).

Much of the book is a warning against the wrong reasons for grasping or holding on to power, followed by an outline of the virtues needed to exercise leadership well. In the first book of

The Pastoral Rule we find this line, which I believe has quietly echoed for some weeks in the Holy Father’s thoughts:

“He must be a man whose aims are not thwarted by the frailty of his body.”

The office of Peter is not just a spiritual thing which discounts human nature. That sacred ministry resides with a person, but that person must have the nature to exercise its rigors.

Benedict XVI has marked his pontificate by humility. If anything, he has tried to depersonalize the use of authority, even that uniquely personal authority, the Petrine Office. Yet we must always remember that the “person” of the Papal ministry is St. Peter, who with his successors acts in the person of Christ.

The papacy is a lived authority and a living authority and one that must respond to the needs of the Age. It is natural that we love the concrete that we know, and love the particular character of our popes.

And we must do our best to accept that like a humble and adored teacher, Benedict now forces on his students a hard lesson: that the teacher should never be the focus of our final attention and love.

{Oh, we all know that - he is the finger pointing to the sun that is Christ, but he was also the Vicar of Christ on earth for the past eight years, and what a Vicar! He has so internalized and assimilated Christ that he radiates Christ.]

Our age has become overly focused on a model of “leadership” which is nothing short of superficial, for whom the shallow gilt of charisma and “personality” have blinded everyone to questions of duty and responsibility. Benedict’s resignation teaches us once again that leadership — while exercised by a person — is not about that person.

Benedict has set before our eyes the old Roman sense of

officium— duty, office, responsibility. Benedict’s embrace of the Petrine office has always been a reluctant one, and that reluctance is born of clear self-knowledge and deep understanding of the history and purpose of papal authority.

The following words are taken from one of the Holy Father’s General Audiences in 2008. He spoke on St. Gregory the Great and his reluctance to sit on the throne of St. Peter, reluctance that gave way to grace, prayer, and action.

Recognizing the will of God in what had happened, the new Pontiff immediately and enthusiastically set to work. From the beginning he showed a singular enlightened vision of the reality with which he had to deal, an extraordinary capacity for work confronting both ecclesial and civil affairs, a constant and even balance in making decisions, at times with courage, imposed on him by his office.

These are not words set down in a theoretical fashion. They rise from the Holy Father’s lips with experience behind them.

More moving are Benedict’s closing words from the following day’s audience. Again, speaking on St. Gregory and his lonely pontificate, he ends:

Gregory remained a simple monk in his heart and therefore was decidedly opposed to great titles. He wanted to be — and this is his expression — servus servorum Dei, servant of the servants of God.

Coined by him, this phrase was not just a pious formula on his lips but a true manifestation of his way of living and acting. He was intimately struck by the humility of God, who in Christ made himself our servant. He washed and washes our dirty feet. Therefore, he was convinced that a Bishop, above all, should imitate this humility of God and follow Christ in this way.

His desire was to live truly as a monk, in permanent contact with the Word of God, but for love of God he knew how to make himself the servant of all in a time full of tribulation and suffering. He knew how to make himself the “servant of servants.” Precisely because he was this, he is great and also shows us the measure of true greatness.

The Holy Father’s reasons for resignation spring from a grave sense of office and a faithful belief in what that office truly is. He has remained through his pontificate faithful and true to his vocation of father and teacher. Both father and teacher must daily put aside themselves to be true to their calling.

The papacy is not a mere person, it is not a great man, it is certainly not a bloodline or earthly principality. It is the ministry of the Bishop of Rome, Successor of St. Peter. It is a sacred office entrusted to the entire Church. It is an enduring stewardship through time. Behind the Vicar stand the Kingship of Christ and the enduring nature of His Church, yesterday, today, and forever.

By the grace of the Holy Spirit, Pope Benedict XVI has resigned. His Holiness has resigned because he understands his office and he wishes with firm resolve to help us to understand this and deepen our faith by remembering him for what he is and by lifting up our hearts and minds to the eternal Father and His Son, Our Supreme Pastor and Lord, Jesus Christ.

[Yes, but Mr. Fahey, you dropped the argument on the one and only reason he resigned - the very real and inescapable fact that advanced age has made him physically incapable of carrying out his mission in the only way he can carry it out and should carry it out: totally and with the maximum excellence. This very practical and logical reason should never be subsumed by all its possible extrapolations, no matter how lofty. The humble worker in the vineyard of the Lord has his feet planted firmly on the ground of realism, but for all that, he is sublime, with a spirit that soars, a heart that thinks and a mind that feels. I'm still giddy from his words this morning after the retreat that "to believe is to touch the hand of God in the darkness of this world". What better motto for the Year of Faith? The amazing things he pulls out all the time from his bag of graces... And we only have five more days of 'exterior visible communion' with him...Now I'm babbling...]

I still have not worked up the gumption to look at how the major newspapers covered THE ANNOUNCEMENT (though I have to do that eventually), because I fully expected the stories to be a hastily amended version of the obituaries they had in store when the time comes. So I was surprised to come across this Op-Ed article that the New York Times published on that fateful day. It is excellent for an instant commentary, even if the writer - who teaches world religions in Smith College - gets it wrong about Regensburg...

The humble Pope

By CAROL ZALESKI

Op-Ed Page

February 11, 2013

NORTHAMPTON, Mass. - POPE BENEDICT XVI is the latest of a small number of popes to resign the chair of St. Peter.

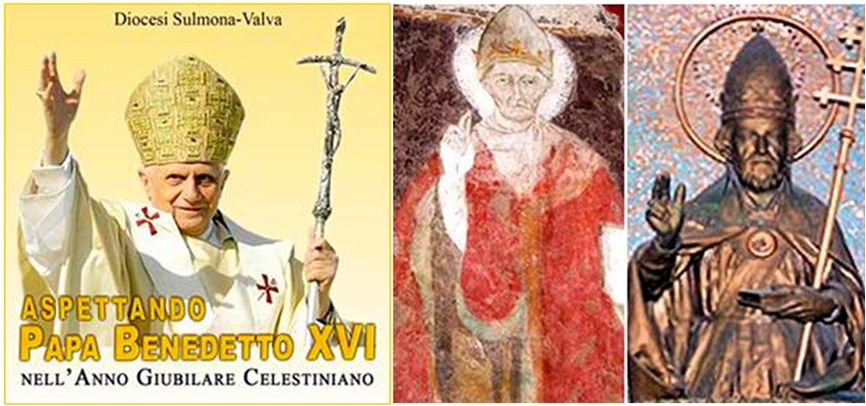

The most famous of these — the one whose resignation had all the earmarks of an abdication — was Pietro del Morrone, Pope Celestine V, the saintly Benedictine hermit who resigned in 1294 after only a few months, realizing that he was called to serve his church through prayer and penance rather than bitter politics and gorgeous, endless public ceremonies. It was a decision Benedict honored.

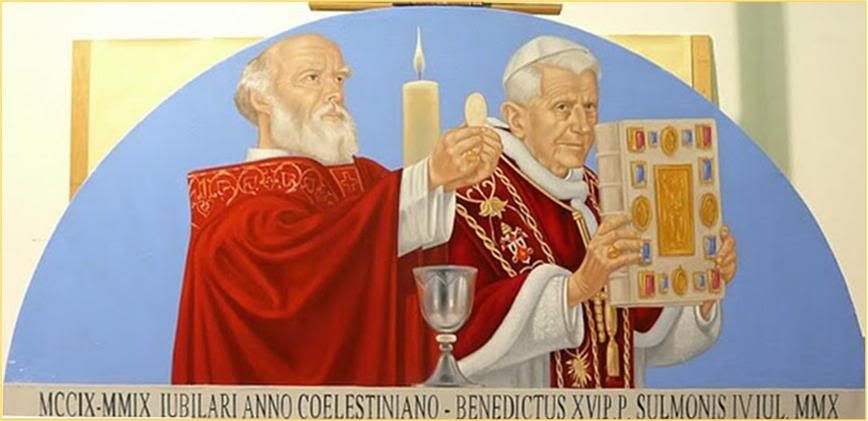

Mural depicting the two Popes in Sulmona Cathedral

Mural depicting the two Popes in Sulmona Cathedral .

It was a decision Benedict honored. In July 2010 he attended the celebration of the 800th anniversary of Celestine’s birth in Sulmona, Italy, and spoke of this medieval pontiff’s capacity for inner silence and “vivid experience of the beauty of creation.”

The previous year, while visiting the same region after a devastating earthquake, Benedict placed his pallium — the narrow band of wool with which he was invested at his inauguration — over the case containing Celestine’s remains, and left it behind. It was a significant foreshadowing of the moment when he too would resign and, like Celestine, face the uncertain verdict of history.

It cannot have escaped Benedict’s notice that, according to a traditional (though debatable) interpretation of “The Inferno,” Pope Celestine is the figure Dante met in the vestibule to hell: “I saw and recognized the shade of one who, through cowardice, made the great refusal.” Anyone who has this job can expect to be misunderstood.

Chief among the misunderstandings of Benedict’s pontificate are those that cluster around the unhelpful label of “conservative.” He is far too astute a scholar and too modern a churchman for such a label to be of much use.

Unfortunately, one still hears him accused of turning the clock back on the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, thwarting the liturgical renewal it mandated and keeping the laity firmly in its place — an impression that would not survive a careful reading of his papal documents alongside the actual texts of the council.

In fact, under Benedict’s leadership, the celebration of Mass, the “source and summit” of Catholic life, has begun to mirror more faithfully the reforms that the Second Vatican Council intended. Beauty is back in season, and millions of Catholics around the world are embracing this change with gratitude.

For the intellectuals of many faiths who admire him, Benedict is a profound religious thinker in the Augustinian tradition according to which the longing for truth is innate and universal and the various disciplines of philosophy, theology and the natural sciences all have as their ultimate aim a personal union with truth.

With his distinctly non-fundamentalist interpretation of the Book of Genesis; his sophisticated handling of recent trends in biblical criticism (most notably, though least noticed, his book “Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life”); his role in the creation of the modern Catholic catechism; and his papal writings on faith, reason and love (beginning with his extraordinary first encyclical “God Is Love”), Pope Benedict has opened a new era in the dialogue between religion and secular reason.

His

errors, of course, have been amply recorded. Less attention has been given to his efforts to make amends.

The speech he made in 2006 at the University of Regensburg was a public relations disaster: one wonders how, in the midst of a deeply thoughtful reflection on faith and reason, he failed to foresee the damage he would cause by quoting, without evaluation, the Islamophobic remarks of a 14th-century Byzantine emperor.

[Too bad even someone like Prof. Zaleski missed the point completely about that citation. It was most definitely part of the deep thought that went into the Regensburg lecture - it was an actual, rare and most dramatic illustration of civilized frank dialog between a Christian emperor, on the verge of being dethroned by the Muslim Turks, and a learned Persian Muslim, who did not scream blasphemy and cut off the emperor's head for what he said about Mohammed, but in fact, sustained further conversations with him enough for the emperor to write a book about it afterwards. To be consistent, the Muslims who protested the citation in 2006 should also have condemned the Persian Muslim for calmly listening to those words about Mohammed, or at the very least, contested that a Muslim could ever have done so! The citation was not just a frivolous footnote in a scholarly presentation, but integral to its thesis of faith and reason. Benedict XVI admitted to Peter Seewald in 2010 that he did not foresee his academic discourse to an audience of scholars would be turned into a cause celebre, but he did not regret making the citation. Besides, Regensburg must never be brought up without mentioning Istanbul and the Blue Mosque as well, because they represent the parameters of Benedict XVI's thinking on reason and faith.]

The upshot of the resulting debate, though, was an improvement in Catholic-Muslim relations, for which Pope Benedict deserves some credit.

['Some credit'? There would never have been any improvement without Regensburg-Istanbul. Istanbul convinced moderate Muslim thinkers that this was no gratuitously provocative Pope but the partner they could have in an effort to stimulate a much-needed Islamic enlightenment, as he had proposed in Regensburg!]

His critique of New Age versions of Buddhism as narcissistic was

poorly phrased, and instantly misunderstood; yet even this gaffe provided an occasion for fruitful dialogue.

[It wasn't poorly phrased, it was poorly translated. But I am happily surprised that Prof. Zaleski used the word 'narcissistic', because the common English account that has been perpetrated of that statement is based on a literal translation of the French phrase 'auto-erotisme spirituel' as 'spiritual masturbation'. An item I posted back in 2009 in the Papa Ratzinger Forum

http://freeforumzone.leonardo.it/lofi/ENCOUNTERS-WITH-THE-FUTURE-POPE-Stories-about-Joseph-Ratzinger-before-he-became-Pope/D354530-4.html

was written by a blogging Buddhist monk who met Cardinal Ratzinger in San Francisco in 1999, and he said about the controversial phrase: "It turns out that the Cardinal's views were written first in a French Catholic journal[he gave the interview in French actually], and in French, the phrase 'auto-erotisme' means 'self-absorption', or narcissism. Unfortunately, the English-language press heard the term without benefit of translation..."

I have not managed to find the original interview given in 1997, but the English translation of the controversial remark quoted in various Anglophone sources puts it thus: "If Buddhism is attractive [to people in the West], it is because it appears as a possibility of touching the infinite and obtaining happiness without having any concrete religious obligations. A sort of spiritual masturbation..." Of course, the statement makes more sense if that offensive translation of 'auto-erotisme' were replaced by 'self-absorption', which has, in fact, been the hallmark of the 'me, myself and I' generations that have emerged since 1968. Indeed, a Buddhist reader, reacting to the monk's blog, observed quite rightly that the cardinal was not referring to Buddhism as such, but to the idea that Westerners have of it. Not surprisingly, the Dalai Lama has consistently polled much higher than Benedict XVI among Germans who are asked about their idea of a spiritual leader!]

He was willing to allow that condoms might have value in preventing the transmission of H.I.V. in Africa. And where bioethics and sexual ethics are concerned, he has sought to clarify the consistent rationale of Catholic teaching, to defend the dignity of the human person, and to carry on the version of feminism that one associates with John Paul II.

Pope Benedict’s announcement that he is retiring — made on the feast day of Our Lady of Lourdes, the World Day of the Sick, on the threshold of an early Lent — was his “Nunc dimittis”

[the old Simeon's canticle at the presentation of Jesus in the Temple, which starts with the words "Now, Master, you may let your servant go in peace, according to your word..." What a lovely and appropriate simile to bring up! Thank you, Prof. Zaleski!]

It is his final summons to a weary Church to look beyond politics and the calculus of power, and to recover its real sources of renewal.

Even the “spiritual but not religious” set might be intrigued by a Pope who, by resigning his position, admits not only his own frailty but that of the throne on which he has been seated.

What I see in Pope Benedict XVI is not the shade of one who through cowardice made the great refusal, but the substance of one who through humility and wisdom made the great acceptance.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 25/02/2013 23:48]