'It was a splendid day...'

'It was a splendid day...'

Foreword by BENEDICT XVI

'On the Teachings of the Second Vatican Council'

from the

Collected Writings of Joseph Ratzinger

Translated from the 10/11/12 issue of

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council, Germany's Herder publishing house will publish in November the conciliar writings of Joseph Ratzinger as part of his 16-volume Collected Writings, under the title Zur Lehre des Zweiten Vatikanischen Konzils (On the teachings of the Second Vatican Council), in two volumes edited by Archbishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller, now Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, who had established the Institut Paspt Benedikt XVI, publishers of the Collected Writings, when he was Bishop of Regensburg.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council, Germany's Herder publishing house will publish in November the conciliar writings of Joseph Ratzinger as part of his 16-volume Collected Writings, under the title Zur Lehre des Zweiten Vatikanischen Konzils (On the teachings of the Second Vatican Council), in two volumes edited by Archbishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller, now Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, who had established the Institut Paspt Benedikt XVI, publishers of the Collected Writings, when he was Bishop of Regensburg.

We publish herewith (in German and Italian) the Foreword to the volumes written by Benedict XVI recalling that time of widespread expectation and great hope, and in which he advocates a reading of the Council that may help in its effective reception into the life of the Church.

It was a splendid day when, on October 11, 1962, with the solemn entrance of more than 2,000 Conciliar Fathers into St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council opened.

In 1931, Pius XI had dedicated this day to the Feast of the Divine Motherhood of Mary, commemorating the fact that 1500 years earlier, in 431, the Council of Ephesus had solemnly acknowledged Mary as The Mother of God to express the indissoluble union of God and man in Jesus Christ.

Pope John XXIII chose the day for the beginning of the Council in order to entrust the great conciliar assembly he had called to the maternal goodness of Mary, and to firmly anchor the work of the Council in the mystery of Jesus Christ.

It was most impressive to see the entrance of bishops from all over the world, of all peoples and races - an image of the Church of Jesus Christ that embraces the whole world, in which the peoples of gthe earth know they are united in his peace.

It was a moment of extraordinary expectation. Great things were to happen. Previous Councils had almost always been called to discuss a concrete question to which they had to respond. This time, there was no particular problem to resolve.

But precisely because of that, there was a sense of general expectation in teh=he air: Christianity which had cuilt and shaped the Western world seemed to be increasingly losing its effective strength. It appeared to have become exhausted to the point that the future would be determined by other spiritual powers.

The perception of this loss of the present by Christianity and the task which followed from it was well summed up in teh word aggiornamento, bringing it up to date.

Christianity must be in the present so it can shape the future. In order that it could once more be a force that can shape tomorrow, John XXIII called Vatican II without indicating any concrete problems nor programs. This was both the greatness and the difficulty of the task that was presented to the ecclesial assembly.

The various episcopates doubtless came to the great event with diverse ideas. Some arrived looking forward to the program that ought to be developed.

It was the central European bishops - from Belgium, France and Germany - who had the most decisive ideas. In the details, the emphasis was necessarily on different aspects, but nonetheless, there were certain priorities in common.

A fundamental theme was ecclesiology, which had to be examined in depth form the point of view of the history of salvation, as trinitarian and sacramental. To this was added the need to complete the doctrine on the primacy of the First Vatican Council through a revaluation of the episcopal ministry.

An important issue for the central European bishops was liturgical renewal, which Pius XII had already started to carry out.

Another central emphasis, especially for the German bishops, was ecumenism: The experience of having to suffer together the persecution of Nazism had brought together many German Catholics and Protestants. Now this had to be understood and carried forward at the level of the universal Church. Then there was the subject of Revelation-Scripture-Tradition-Magisterium.

The French bishops gave priority to the relationship of the Church with the modern world, in practice, work on the so-called Schema XIII that would later give birth to the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the contemporary world (Gaudium et spes[Joy and hope]).

This dealt with the true focus of expectations from the Council. The Church which, even as late as the Baroque era, had shaped the world laterally, had since entered into an increasingly negative relation with the modern era, which began in the 19th century. Should things remain that way? Could the Church not take a positive step forward in these new times?

Behind the vague expression "the world today' was really the question of relating to the modern age. In order to clarify what the relationship should be, it would be necessary to better define what was essential and constitutive of modern times. This was not achieved by Schema XIII.

And even if the Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et spes expressed many important points in order to understand 'the world' and gave relevant contributions on the subject of Christian ethics, it was also unable to offer the substantial clarification required.

Unexpectedly, the encounter with the great themes of the modern age did not take place in the major document of the Pastoral Constitution, but in two minor documents of Vatican-II, whose importance only emerged little by little with the reception of the Council.

First of all, the Declaration on Religious Freedom, which was requested and prepared with great attentiveness most especially by the American bishops.

The doctrine of religious tolerance as it had been elaborated on by Pius XII no longer seemed adequate in the face of the evolution of philosophical thought and the modern concept of the State.

Religious freedom has to do with the freedom to choose and practice a religion, but also the freedom to change it, as a fundamental human right. In its most intimate motivations, the concept of religious freedom could not be alien to the Christian faith which had entered the world claiming that the State cannot determine truth and cannot demand any kind of worship.

Christian faith claimed the freedom of religious belief and its practice in worship, without violating the law of the State in its own domain: Christians prayed for the Roman emperor but did not worship him.

From this point of view, it can be stated that with its birth, Christianity brought the world the principle of religious freedom. Nonetheless, the interpretation of this right to religious freedom in teh context of modern thought was still difficult, because it would seem that the modern version of religious freedom presupposed the inaccessibility of truth to man, thus displacing the religion to the realm of the subjective.

It was certainly providential that 13 years after the Council ended, Pope John Paul II came on the scene from a nation in which religious freedom was contested by Marxism, namely, from a specific form of a modern philosophy of the State.

The Pope came from a situation that was almost like that of the ancient Church, since the intimate place of faith in the issue of freedom, especially feedom of religion and of worship, was once more newly visible.

The second document that would show itself to be increasingly important for the encounter of the Church with modern times was born almost by chance and developed at various levels. I refer to the declaration Nostra aetate on the relationship between the Church and the non-Christian religions.

Initially, the intention was to prepare a declaration on the relationship between the Church and Judaism, a text that had become intrinsically necessary after the horrors of the Shoah. The Conciliar Fathers of the Arab nations did not oppose such a text, but they pointed out that if the Council were to deal with Judaism, it also had to say something about Islam. How right they were would be understood in the West only little by little.

Finally, the intuition grew that it would be correct to speak of the two other great non-Christian religions, Hinduism and Buddhis, notg to mention, the theme of religion in general.

To all this was spontaneously added a brief instruction regarding dialog and collaboration with other religions whose spiritual, moral and socio-cultural values must be acknowledged, conserved and promoted (cfr No. 2).

Thus, a precise and extraordinarily dense document initiated a theme whose importance at the time of the Council was not foreseeable. The magnitude of the task implied, how much effort was necessary to clarify and understand it, have since been increasingly evident.

During the process of its active reception, a weakness of this text also emerged that is in itself extraordinary: It speaks of religion only in a positive way and ignores the pathological and disturbed forms of religion which have a great impact from the historical and theological viewpoints. Because of this [improper use of religion], the Christian faith itself has been widely criticized both within the Church and outside it.

While the central European bishops and their theologians may have had a dominant influence at the start of the Council, the radius of work and common responsibilities increasingly widened during the Council.

The bishops recognized they were apprentices in the school fo the Holy Spirit and in the school of reciprocal collaboration, but precisely in this way, recognized that they were all servants of the Word of God who live and work in the faith.

The Conciliar Fathers could not and did not want to create a new and different Church. They had neither the mandate nor the authority to do so. They were Conciliar Fathers with a voice and the right to decide only as bishops, that is to say, by sacramental virtue in the sacramental Church.

And so they could not and did not want to create anew faith or a new Church, but rather to understand both the faith and the Church more profoundly in order to truly 'renew' them. That is why a hermeneutic of rupture is absurd and contrary to the spirit and to the will of the Conciliar Fathers.

In Cardinal Frings, I had a spiritual father who lived this spirit of the Council in an exemplary way. He was a man of strong openness but he knew that only faith can guide us towards the open, to that wide horizon that remains pre-emptively closed to the positivistic spirit.

It is that faith that he wished to serve with the mandate he received upon his episcopal ordination. I cannot but be forever grateful that he had asked me - at the time, the youngest theology professor in the University of Bonn - to be his theological consultant at that great ecclesial assembly, allowing me to be present at the school of the Council and follow its course from within.

This volume assembles the various writings with which, in that school, I asked to be heard. They are requests that are fragmentary, which also show the process of learning that the Council and its reception meant and still mean to me.

I hope that these contributions, with all their limitations, can altogether help to understand the Council better and to translate it into the right ecclesial life.

With all my heart, I thank Archbishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller and his co-workers at the Institut Papst Benedikt XVI for the extraordinary effort that they took on in order to publish this book.

Castel Gandolfo

Feast of St. Eusebius of Vercelli

August 2, 2012

There is obviously much more to the Joseph Ratzinger of Vatican II that the world has not been privy to, and these new volumes should be an amazing mine of new discoveries. The Foreword in itself already uncovers quite a few facets previously not seen.

One can imagine the ferment these two volumes will cause in the world of Church historians - not to mention the commentariat and the chatterati. Writings which not a few will seek to mine not so much for the contemporaneous insights that the younger Joseph Ratzinger had about the Council and its issues, but for anything they might be able to point to as contrary to his statements and actions as Pope (a chop-licking, lip-smacking exercise voraciously indulged in by the Mellonis and Komonchaks out there.

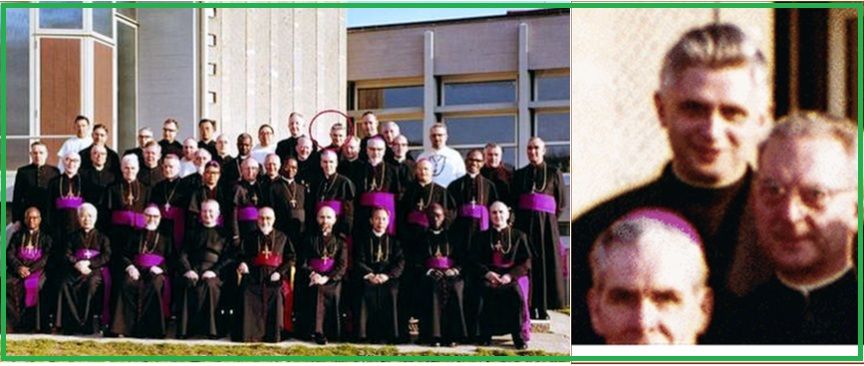

Joseph Ratzinger with the Vatican-II commission on missions which drew up the final decree Ad gentes in 1965 at the Servites' retreat house in Nemi near Castel Gandolfo. In the right photo, the Venerable Fulton Sheen is the man in front, left, of Ratzinger.

That incisive and engaging

Joseph Ratzinger with the Vatican-II commission on missions which drew up the final decree Ad gentes in 1965 at the Servites' retreat house in Nemi near Castel Gandolfo. In the right photo, the Venerable Fulton Sheen is the man in front, left, of Ratzinger.

That incisive and engaging

young theologian brought to

Vatican-II by Cardinal Frings

by Elio Guerriero

Translated from

Oct. 11, 2012

Elio Guerriero (born 1948) is an Italian theologian who is the editor of the Italian edition of the works of Hans Urs Von Balthasar, as well as the editor of the Italian edition of Communio, the international theological journal founded after Vatican-II by Von Balthasar, Henri de Lubac, and Joseph Ratzinger, among others.

At the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church was represented for the first time in an ecumenical council by bishops coming from all the continents.

Then there were rhe observers from other Christian communities and almost 500 experts on various Church disciplines who were called to provide the Council Fathers with a scientific basis for their interventions.

The texts that were to be the basis for Council discussions had been prepared by various committees in Rome and sent on to the Council Fathers in advance. for their study. Not all the episcopates prepared adequately.

A book with the suggestive title,

The Rhine flows into the Tiber, highlights the role played by the nearly 60 German-speaking bishops at the Council, among whom a leading protagonist was Cardinal Josef Frings of Cologne.

By his side was a young theologian from Bavaria, Joseph Ratzinger, who had been teaching fundamental theology at the University of Bonn since 1959. There, he had developed a close friendship with Hubert Jedin, the great historian of the Council of Trent, a circumstance that led Prof. Ratzinger to seriously 'prepare' for the Second Vatican Council announced by John XXIII in January 1959.

Invited to give a lecture about the coming Council at the Catholic Academy of Bamberg near Cologne, the young professor caught the admiring attention of Cardinal Frings, who then started consulting him on the advance schema or draft documents sent from the Vatican, and asked him to be his tehological consultant at the Council.

Ratzinger arrived in Rome on October 9, 1962, and the following day, he made a presentation to the German-speaking bishops criticizing the schema on "the sources of Revelation", which had been prepared by the Theological Commission in Rome.

His critique was severe. Making full use of his prevous studies on St. Bonaventure, he questioned the assumption that 'Scripture and Tradition' were the 'sources of Revelation', as well as the concept of 'inerrancy', and postulates about the relationship between the Old and New Testaments.

By the middle of November 1962, Cardinal Frings brought up his consultant's critique formally in the Council discussions. Subsequent voting on the draft document showed that many of the Fathers objected to a the text which they considered "alien from the language and ideas of the Fathers of the Church and of the Council".

Pope John XXIII had to intervene personally to salvage the situation. He ordered the disputed shema withdrawn to be re-elaborated by a mixed commission that would not simply be drawn from the Roman Curia and academia.

It was not until the fourth and last session of the Council in 1965 that the commission was able to present the definitive text of the Constitution on Divine Revelation,

Dei verbum, which is considered by many to be the most original and innovative of the Vatican II documents.

Ratzinger also carried out similar work for the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church,

Lumen gentium. In this case, he started out from his study on the People and the House of God in St. Augustine - which had been the subject of his doctoral thesis in theology.

He pointed out that in Scripture, the expression 'people of God' did not have a sociological significance but a theologico-sacramental one. In the Old Testament, it was God who gathered the chosen people, and in the New Covenant, it is Jesus who unites the Church around the Eucharistic table.

This brief recollection intends to show that when Pope Benedict XVI speaks of the place of Vatican-II within the living Tradition of the Church, he does not at all mean to diminish the novelty of the great ecclesial event in which he had personally taken part.

When he convoked Vatican II and specified that its principal characteristic would be pastoral, John XXIII was following the impulse of the Holy Spirit, seeking to illuminate and lead the faithful and all men of good will to accept and bear witness in our time to Christian Revelation.

Fifty years since Vatican-II begun, the Year of Faith is an invitation to communion with God, to announce the Word that warms the heart and takes us through the door of faith.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 12/10/2012 02:56]