The pope’s ‘paradigm shift’

The pope’s ‘paradigm shift’

and its true import

Translated from

June 29, 2018

In the book

Il 'cambio di paradigma' di papa Francesco. Continuità o rottura nella missione della Chiesa?(Instituto

Plinio Corrêa de Olivera, 216 pp), José Antonio Ureta seeks to draw up a balance sheet of Bergoglio’s pontificate after five years,

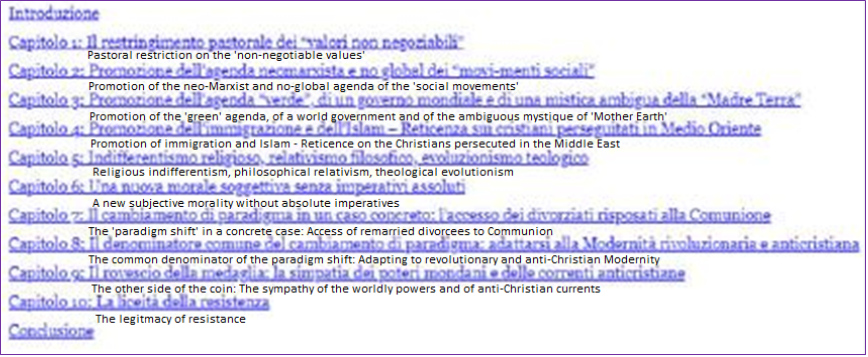

and the titles of the chapters into which he subdivides the text can well summarize the content of the author’s arguments. So it

suffices to list the titles to understand what Ureta thinks of Bergoglio’s doctrinal, pastoral, social and political line.

First of all, Ureta sees in Bergoglio’s Magisterium a ‘pastoral restriction on the non-negotiable values’ that were at the center

of the teaching of both St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI. This is followed by chapters dedicated to Bergoglio’s main secular obsessions.

And after providing an example of this ‘paradigm shift’ focused on allowing communion for remarried divorcees, Ureta discusses “the common denominator of the paradigm shift” introduced by Bergoglio ass the attempt to “adapt to revolutionary, anti-Christian modernity”.

[I think rather than ‘modernity’ per se, ‘modernism’ - as used by the Church since Leo XIII and Pius X to describe all the objectionable anti-Christian features of modernity - is the more appropriate term.] An effort well demonstrated by “the other side of the coin”, namely, “the sympathy of the worldly powers and anti-Christian currents” for this pontificate.

Before his conclusion, in which the author explicitly writes about the ‘confusion’ prevailing in ‘the Church’ today and arrives at taking note of a possible ‘practical scission’ as a consequence of the ‘virtual division’ between two currents that are clearly opposed to each other, Ureta asks

whether there can be ‘legitimate resistance’ to a magisterium which under many aspects no longer appears to be Catholic, and the answer, considering the preceding arguments, is obviously that resistance is not just possible but dutiful and obligatory.

What Ureta proposes has, for some time, been at the center of analyses that other writers have done in various forms, each one according to his own style. Everything that Ureta explains and underscores with great clarity – with recourse to a rich apparatus of citations – is verifiable, and for many Catholics, a source of great pain.

Some observers (only a few really) became aware of it right away, others needed a little more time to get to it.

[Which is understandable because the very idea that the pope himself should turn out to be so anti-Catholic in itself had always been unthinkable. Especially since this pope started out being called ‘the best pope that ever was’, which was a totally unwarranted and unsupported ‘rush to judgment’ analogous to but far worse than the awarding of a Nobel Peace Prize to Barack Obama when he had just taken office! The novelty of a pope being so totally and unconditionally heaped with hosannahs from ‘the world’ was obviously heady enough for most Catholics who readily bought the myth – and consequently, would be and are most unlikely to ever see anything wrong in a ‘pluperfect pope’ also hailed as ‘the most popular man who ever walked the earth’.]

But it is a fact that Ureta’s concerns appear justified.

[That is quite an understatement, Mr. Valli.] I would say that it lacks just another step to go deeper. One must ask: Why is all this happening? Which way is Bergoglio headed? What is his plan? And to try to give an answer, I think one must start from the observation that, in fact,

among all the many things this pope has said and written, one can find all the objectionable things Ureta and others point to, but one can also find their opposite, or almost, anyway.

Let’s take, for instance, ‘non-negotiable values’. It is true Bergoglio has said it is no longer necessary to strike at the same keys all the time

[i.e., he does not think it is necessary to restate the Catholic position on these values over and over because, as he claims, ‘they are well-known to everyone” – ignoring, of course, that these values have had to be reaffirmed over and over by his predecessors precisely as a response to the constant assault of the world that has sought to finally obliterate Catholic teaching altogether in our day]. And he has even said that he doesn’t understand the very term ‘non-negotiable values’ itself.

It is also true that he has spoken of families with many children in terms that are hardly flattering (“breeding like rabbits”), and it is true that he has not really descended into the arena to defend the rights of the unborn with the power and consistency that his predecessors did, and indeed, at times, he has seemed to distance himself from those who are on the frontlines of the fight to save the lives of unborn children.

But at the same time, we can find words in which he defends the traditional family as that formed by a man and a woman in the state of matrimony, and occasionally, against abortion and euthanasia.

[Of course, we can – when he has no choice but to say them, in all those pro forma statements that a pope unavoidably has to make, if only to reassure the faithful he is still a Catholic. Even though he still gets it wrong - as Valli himself critiqued the pope's recent address to the Association of Italian Family Forums, in which he paid lip service to marriage as between one man and one woman and called abortion on demand as ‘Nazism with white gloves’ or something equally silly. The difference is that he speaks about all the items on his personal agenda for action with a passion and conviction, and with a frequency and consistency, that one does not find at all in his ‘Read-my-lips-I-am-a-Catholic’ protestations.]

As for what Ureta defines as his ‘promotion of immigration’

[here again, I would use the term immigrationism, not immigration per se, because it is not so much the actual immigration that Bergoglio advocates as much as the very idea – and ideology - that immigration is a ‘fundamental human right’ that can only be a fountainhead of benefits for the host countries and must therefore be favored and accommodated at whatever cost!] – it is useless to pass in review all the interventions this pope has expended admonishing ‘welcome’ for all immigrants wherever they may choose to debark. But in his words, we have also noticed a subtle and gradual adjustment which has, over time, forced him to acknowledge the difficulties faced by the host countries so that he now speaks generically of ‘refugees’ rather than’ immigrants’.

[A matter of cosmetic semantics, really, which does not change the burden and intent of Bergoglio's immigrationist advocacy. Genuine refugees do have a theoretical and legal right to seek asylum in other countries, whereas undocumented immigrants have no such analogous right, albeit the United Nations and the secular world - and with them, Bergoglio - have endowed them with the 'right' to be admitted to any country in violation of that country's immigration laws, in much the same way that liberals have declared every woman has a 'right' to abortion.]

Finally, it is true that on doctrinal aspects, we can find in Bergoglio a tendency towards ‘liquidity’, towards the primacy of ‘pastoral practice’ over doctrine, and of subjective experience over generally binding norms, but he also speaks about the centrality of Jesus and that Christians must not abandon the Cross.

[More pro forma lip service. Yet in his propaganda videos promoting the 'equality' of all religions, you will never ever hear him say the word Christ, lest other religions accuse him of being intolerant of all who are not Christian!]

In short, with the passage of time, the true characteristic of this pontificate appears to be be that of giving the papacy a connotation that we could well term ‘political’ in a lateral sense.

What do politicians do? They often say and do not say, one day they say A, the next day B, one day they place the emphasis more on A, the next day more on B.

The logic of politics is that of ambivalence, depending on who the interlocutor happens to be and on the circumstances. For the politician, nothing exists as absolute, but everything can be modified.

The typical response of a politician is “It depends…”, and we can see that Bergoglio the Jesuit, in general, proceeds precisely in this way. A typical example is the answer he gave at the Lutheran church in Rome to a question about interfaith communion, when his answer – extremely confused – could be substantially summarized as

“maybe yes, maybe no, I really don’t know, it depends, decide for yourself”.

[A great illustration of Bergoglio’s thinking. It’s not that he does not have an answer: he knows exactly what he thinks about whatever it is he decides to speak or write about. On interfaith communion, for instance, he has hardly tried to dissimulate that he is all for it, in other circumstances when he is actually saying Yes without having to say it explicitly, as in his latest “No one is putting a brake to intercommunion” when asked about the German bishops’ ‘unofficial’ publication of their guidelines allowing the practice. Of course, he found no fault with the German bishops who seemingly ‘defied’ Bergoglio’s admonition via the CDF not to publish the document (not because of its content) but because ‘it was not ready for publication’. Not ready because the text needed more editing, or not ready simply as a matter of timing?

One might note Bergoglio plays this game only and always on matters involving Catholic doctrine and possible heresy or apostasy with regard to it, i.e., ever careful not to give any of his critics the opportunity to catch him red-handed in an act or statement that is clearly and unequivocally heretical or apostate, thereby enabling them to accuse him of material heresy. He’s not about to risk losing the papacy – and all the powers it gives him – by opening himself to the possibility of any such accusation. Better to sound muddled than to self-incriminate himself by plain talk and have Cardinal Burke, Bishop Schneider, and the entire militant Catholic blogosphere finally slap him down with a solid GOTCHA! accusation that meets the letter and the spirit of canon law on heresy and/or apostasy.]

It is basically the same logic that we find in Chapter 8 of AL in its proposal of situation ethics within a document that elsewhere appears to raise a hymn to sacramental marriage and on the family based on such a marriage. [And that perhaps is the supreme way in which Bergoglio is ever the politician – his ability to lie unflinchingly and/or contradict himself in the same breath. What does it serve to sing the praises of sacramental marriage and then concede that circumstances can be ‘discerned’ that justify violating everything Jesus taught about marriage and adultery, saying in effect that adultery is not always a sin?]

I have had occasion in the past to define Bergoglian logic as ”Yes but also no; no but also yes” since everything to him is fluid, indeterminate. Prof. Roberto Pertici in the essay he published not too long ago on Sandro Magister’s blog

spoke properly and opportunely of Bergoglio’s pontificate as ‘the end of Roman Catholicism’.

The Bergoglian paradigm shift is not so much in the attempt – which is ongoing – to come to terms with Modernism and enjoy the accolades and deference from the masters of contemporary secular thought, but in the process of deconstructing the papacy that Bergoglio has set into motion from the very beginning.

From the iron logic of the

Dictatus papae [Papal Dictation]

[a compilation of 27 powers attributed to the pope and published under Pope Gregory VII in 1075, advancing the strongest case for papal supremacy and infallibility], we have now come to what I call ‘politics’ which, as Pertici writes, “ends up by making an issue of the very principal of authority”.

Nor does Bergoglio do it out without awareness or from distraction, but because he really wishes to follow this line:

to minimize the juridical, hierarchical, authoritative and external features of the munus petrino [the Petrine office] while emphasizing its pastoral, dialoguing, anti-dogmatic weight in ‘the world’ to which it seeks assimilation to the point that the logic of the world becomes his logic.

The ‘peripheral character’ (as defined by Pertici) of Bergoglio’s formation certainly weighed for much in his concept of the papacy. It is one thing to be born and raised in Europe, and quite another thing to be ‘formed’, even in the ecclesial sense, in Argentina. Pertice says that

Bergoglio is so rooted in the Latin-American world that he is unable to incarnate in himself the universality of the Church. So even this must be taken into account in order to understand the deconstruction taking place in the Church today.

On the other hand, the obvious sympathy that Bergoglio has for Lutherans and the Protestant world is significant. For them, deconstruction – and everything it brings by and with itself – did take place, as did the depotentiation of authority and the decentralization of religion.

The real ‘forcing through’ on the part of Bergoglio is taking place In ecclesiology. In which he repeatedly underscores the importance of ‘the people’, to whom he gives an almost mystical [and mythical] dimension. In the center we no longer have the pope’s auctoritas, as the rock on which the church is built, but rather, the way that ‘the people’ must travel together, which is the literal meaning of the ‘synodal’ process.

This is also explains his preference for using the image of a polyhedron [with its theoretically infinite variations] to represent the church or any given community, rather than the sphere which is an image of perfection. He says he has never been attracted by perfection, nor the principle of non-contradiction, nor by structured thought, but rather by non-uniformity, by the encounter with diverse attitudes, by multiculturalism.

[In short, he revels in what he must think of as his ‘anti-intellectualism’. Yet in every interview he gives, he does not miss the chance to show off his erudition, sometimes on arcane matters, but who can doubt he also wants to ‘prove’ to everyone that he is a substantial ‘thinker’ as his two immediate predecessors were? Hence that ‘intellectual biography’ of him published last year – if a book can be written about it, his intellectual grounding must be pretty solid and impressive, right? And the Vatican’s instant mini-book series about ‘the theology of Pope Francis’ which Mons. Vigano thought he could ‘use’ Benedict XVI to endorse.]

Indeed, as he often says, he sees his task not as seeking solutions but as getting processes started. And so

he sees the Church “almost as if it were a federation of the local Churches”, in Pertici’s words,

each of them endowed with ample disciplinary, liturgical and even doctrinal powers”. [Ah so! “The United Churches of Bergoglio”! Whatever happened to the Church of Christ as a universal Church, a truly ‘catholic’ Church – in which I can go anywhere on the planet and have reasonable assurance that I will find myself at home in any church and in any Catholic liturgy celebrated anywhere on earth!]

Indetermination

[Might ‘equivocation’ be a more appropriate term?] is part of the design. Where should this common path lead? What would be the goal for that ‘discernment’ that is so often invoked these days? Does one see better from the peripheries? What direction is the ‘outward-going church’ headed for? Do not expect answers, because the pope himself is less interested in answers than in just getting ‘the process’ underway!

In short, there certainly has been a paradigm shift in the Church, and it is profound. Yet it concerns above all and substantially, the figure of the pope and the nature of the Pontificate. [Typically narcissistic, everything somehow ends up being about him !]

As for Ureta’s reflections on the legitimacy and need for criticisms of the pope, the discussion is open.

With the hope that the current ‘virtual division’ among Catholics of diametrically opposing views and sensibilities will never come to a formal schism! Because that would be the true tragedy.

Edward Pentin discussed the book with the author...

How should Catholics respond

to the pope’s ‘paradigm shift’?

Chilean author José Antonio Ureta believes faithful ‘resistance’

to destructive innovations is a necessary act of charity

July 5, 2018

In view of the “paradigm shift” said to be taking place during this pontificate, one that critics say breaks with the Church’s teaching and tradition, how should a concerned Catholic respond? Is it legitimate, for example, to resist Church authority, including perhaps even the Pope, and if so, how?

Chilean author José Antonio Ureta offers some answers to these questions in his new book,

Pope Francis’ Paradigm Shift: Continuity or Rupture in the Mission of the Church? — An Assessment of his Five-year Pontificate. The book has yet to be published in English but a detailed summary by the author can be found here

https://issuu.com/ureta.jose/docs/lecture-at-conference-on-neomodernism?e=33361900/63009532

In this June 23 interview with the Register in Rome on the sidelines of a conference examining new and old modernism, Ureta explains where he and others believe that Pope Francis is erring, why resistance to error is an act of charity rather than dissent, and why he believes

the term “paradigm shift” can only really apply to one event in the life of the Church: the Incarnation. The author also warns against the temptation to sedevacantism (the belief that the See of Peter is vacant), which he says is “no solution at all.”

Ureta is a member of the Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira Institute founded by the eponymous Brazilian Catholic thinker. The Institute to which Ureta belongs says it takes Oliveira’s “filial, sincere, and loyal spirit” to the Pope “as a model” and that resistance is a part of that. “It is not revolt, it is not acrimony, it is not irreverence,” the institute says in publicity that accompanies Ureta’s book. “It is fidelity, it is union, it is love, it is submission.”

Mr. Ureta, what made you want to write this book? Why did you feel this book needed to be written?

I think a lot of people — ordinary, good Catholics — are distressed with all the changes they see with this papacy. They are perplexed, they are confused, and they don't know what to say, what to do.

And so some of them say: “Well it’s the Pope or the bishops who are the leading magisterium so we have to follow. I don’t understand, but I will follow.” Others are getting so distressed that they say that all this is just pure heresy, and so if these are heresies he cannot be the Pope. Then they put one foot at least on this very slippery slope of sedevacantism which is no solution at all.

So [the book] is to show to them that it’s true:

There are very distressing statements and gestures, they don’t correspond to the traditional teaching of the Church, but they don’t involve infallibility. The popes can err and the bishops obviously can err when leading the Church into such a direction. We have the right to resist because St. Paul said “If we or an angel from heaven should preach [to you] a gospel other than the one that we preached to you, let him be anathema.”

So I took as issues the abandonment of the non-negotiable values. The accepting the neo-Marxist agenda of the social movement, these radical ecologies, immigration. Obviously on normal things the Pope can err and he is erring. So I go through each of them, with a lot of references — there are like 500 references.

Everything is just quoting his own words. It’s very well documented and so it’s undeniable that he is teaching or promoting wrong things. But we can disagree, we can resist. And what this book presents is a kind of middle of the way, a balanced attitude that any Catholic can take.

So what’s the solution for you? And what do you say to those who are perhaps tempted by sedevacantism? What is the answer to come to terms with the issues you mention?

The first is obviously to preserve our faith. That is our duty because it is our salvation, and the salvation of others, maybe people in the family. So we need to stick with the traditional faith. Now, that is a very practical and serious problem:

Can we still receive the teaching of the Church from the lips of those pastors who are demolishing the Church? Can we receive the sacraments from their hands?

It’s a very difficult question because in the same way in the family, the relationship between a child and his father presupposes confidence. The relationship between the faithful and the pastors has to be in a climate of confidence, but now these pastors are so engaged in this self-demolition that there are no conditions for such coexistence (or

convivenza in Italian which is more expressive) — this familiar coexistence between pastors and the flock. So I think that in those cases we can stop a kind of daily coexistence with those pastors, and then come close to those who really defend true Catholic doctrine.

You say in the book: “The reader will find clear and substantiated answers to these questions over these five years of this pontificate, both in the doctrinal field and regarding the conduct that one should have.” Could you expand on what you mean by that?

It is mainly in the last chapter on resistance. The answer is precisely this: Theologians throughout history have insisted that because the charism of infallibility doesn’t cover every teaching and every gesture, every act of the pope or of the pastors, they can err. And if we are using our reason, we can recognize anathema with the teaching of our Lord and Savior in the gospel, and then recognize this disagreement.

We have the full right not to follow these novelties that are not guaranteed by either the previous dogmatic definition or the universal teaching of the Church — Quod semper, quod ubique, quod ab omnibus (That which has everywhere been believed in the Church, always been believed, and by all universally). And so there are a lot of quotes from theologians regarding this initiation of resistance.

You talk about resistance not as revolt, not as acrimony, and not irreverent but as an act of fidelity. Do you see that as an important point to get across, because some people say, for example, that the DUBIA represented an act against the Pope whereas its authors see it as an act of charity to the Pope and to the faithful, to ensure he does not err. Is that also the point you want to get across?

Exactly, because when someone does something wrong, a fraternal correction is an act of charity. Not warning of the mistake that’s being committed is complicity with the evil that's being done and with the bad effects of this evil on the person who had carried these out. So it is an act of charity and, yes, it’s very difficult to enact not fraternal but filial charity, because then how does one do it in a very respectful manner? But there are situations where we have to, even in our family lives. We have to. If we don’t, we are not fulfilling our filial obligation.'

On the definition of “paradigm shift': What should people understand by that? For the ordinary Catholic, how can they better understand what they’re trying to do with this paradigm shift?

It’s a very confusing use of the term. We can understand that in science to some extent there are some paradigm shifts.

In religious matters there was one paradigm shift, which was the Incarnation and Redemption of our Lord Jesus Christ. So we passed from the ancient law which didn’t save by itself through to the new law where we are saved.

So this is the real paradigm shift which actually is the kind Cardinal Kasper doesn’t recognize because he says that for the Jews, salvation is still about being faithful to the ancient law. So for them there is no paradigm shift. But now he proposes a paradigm shift for Catholics.

After our Lord came down to earth and became man, it is not possible to have another paradigm shift in the faith because that would mean that we are n denial of our Lord - by somehow turning away from him, departing from his teachings and from his saving actions.

But could it also mean, as some of its proponents contend, bringing the Church “up to date,” bringing her into the 21st century, into a fuller engagement with a whole new world which is different than how it used to be? Is here any truth to that?

The Church is one and is apostolic. She cannot suffer a metamorphosis in order to become something different than it was in the beginning.

Based on what the world is like?

Exactly. The great 18th-century theologian Jacques-Bénigne Lignel Bossuet said

“the Church is Christ shared and communicated.” So if the Church separates from Christ, there is nothing more to share, and nothing more to communicate, and what is being communicated is basically whatever the Church has received from the world!

So now we have to go out and preach again, since we’re living in a very neo-pagan society. Are we to adopt neo-pagan values to evangelize this neo-pagan society? St. Paul’s letter to the Corinthians is very interesting: Corinth at the time, because of the geographical situation, was a crossroads, with a lot of merchants and military men traveling through. So it was also a city of corruption, of prostitution. Plus, in earlier times, the people there worshipped a goddess of fertility. To these people, St Paul, in his letter to the Corinthians, preached not only fidelity in marriage but also virginity. For the first time, the Church proclaimed the ideal of virginity. To whom? To those who denied it.

At present, for instance, there’s this new [Oct. 3-28] synod on the youth. They’re saying now that all these young people don’t share at all the Church’s teaching on sexuality and this and that. Well, those are like the Corinthians whom St. Paul saw. Let’s preach to them the ideals of chastity and virginity.

The following reviews a much earlier book than the spate of books in 2017-2018 critical of Bergoglio...

An idiosyncratic guide to

An idiosyncratic guide to

papally-minimalist, free-market Catholicism

John Zmirak’s 'Politically Incorrect Guide to Catholicism' is a witty, acerbic,

and clear book that shows up the ongoing crisis in contemporary Catholicism

by Leroy Huizinga

July 9, 2018

Recent months have seen the publication of several books critical of Pope Francis’s exercise of the Petrine office. Phil Lawler, Ross Douthat, and Henry Sire have all issued tomes critical of the direction Francis is taking the Church.

Contrary to the accusations of certain self-anointed Franciscan Fanboys come rather lately to ultramontanism, many of those uneasy with the direction of the Church under Francis are thoughtful people of substance and good will who developed grave concerns after a period of cautious optimism early in the current pontificate.

Perhaps Francis was engaging in a radical new style of papal display while maintaining the substance of Catholic teaching, a strategy very much in keeping with Pope St. John XXIII’s understanding of the very purpose of Vatican II, which was to keep the substance of the Faith while adapting forms of its expression to modern man’s needs and modes of understanding.

For instance, Matthew Schmitz of

First Things has recounted that he was able to appreciate and esteem Pope Francis’ early statements and documents using the lens of the hermeneutic of continuity.

But the synods on the family and Amoris Laetitia foreclosed that possibility going forward:

I was not then, and never will be, against Francis. In June of that year, I celebrated the publication of Laudato Si’: “Francis’ encyclical synthesizes the great cultural critiques of his two most recent predecessors.” I was glad to see Francis smashing the false idols we have made of progress and the market. […] [I seem to have missed this part of Schmitz's 'conversion' story, and I am sorry I think less of him now because of his misplaced and misguided plaudits for Laudato Si, a greatly flawed encyclical that espouses false science and all its falsehoods!]

My admiration for Laudato Si’ has only grown with time, but I fear the import of that document is bound to be obscured by Amoris Laetitia. A pope who speaks with singular eloquence of our need to resist the technocratic logic of the “throwaway culture” seems bent on leading his Church to surrender to it. What is more typical of the throwaway culture than the easy accommodation of divorce and remarriage?

And so I ended up criticizing Francis — the pope for whom I once had such great hopes — in the pages of the New York Times. “Francis has built his popularity at the expense of the church he leads,” I wrote. How little I had wanted to arrive at these conclusions — how much I had dragged my feet along the way.

Schmitz is representative of many thoughtful Catholic intellectuals (Phil Lawler has recorded his own shift);

it’s easy and honest to read much of what Francis wrote in (say) Evangelii Gaudium and Laudato Si’ in true continuity with what Benedict (and John Paul II) before him had taught. [And we're back at Bergoglio's pro forma 'Catholic' formulations! How can you take any of it seriously when in his genuinely Bergoglio statements - i.e., thoughts attributable to him alone and not to any other pope - are so anti-Catholic!] A fun game on social media early in Francis’s papacy was to post a papal quote and query one’s followers about which pope said it as a way of illustrating continuity among the three.

And yet the synods on the family and the resulting Amoris Laetitia proved a tipping point, where cautious optimism about Francis gave way to concern and loyal opposition in a sort of Emmaus moment, where for many their eyes were opened and they saw the Vicar of the risen Christ for who they now think he is: a radical dedicated to changing the Church in accord with the mischievous Spirit of Vatican II.

John Zmirak was there first. A witty, acerbic, and informed writer, he struck an anti-Francis tone from the first. And so the recent spate of books critical of Francis warrants taking a look at Zmirak’s

Politically Incorrect Guide to Catholicism, issued back in 2016. Zmirak describes his aim for the book as follows:

It’s my task to throw a wet blanket on the hootenanny that began with the election of Pope Francis and help the reader discover” that fundamental Catholic teaching and practice can’t change on matters of politics, economics, love, marriage, sex, and resistance to “evil ideologies” from “Islam to feminism, Nazism, and communism. (pp. 3-4)

Zmirak attempts to support

a papally-minimalist, free-market, pro-life, pro-marriage understanding of Catholicism by discerning a solid core of official Catholic articulation of the Tradition, interpreting certain documents and movements (such as “Catholic Social Teaching”) in ways counter to progressive readings, and claiming other documents and statements don’t represent the true Tradition.

Zmirak’s book puts into bold relief the problem faithful Catholics have in the post-conciliar era. It presents a defensible but idiosyncratic reading of modern Catholicism and a proposal for how faithful Catholics should situate themselves within it.

Zmirak begins the book with a couple of chapters covering basics, setting up general principles to move to his particular critiques. After running through some introductory preliminaries addressing the confusion many outside and inside have about Catholicism, the first chapter,

“The Church: What It Says about Itself, the World, and What Will Happen to you When You Die”, presents an efficient and helpful rehearsal of salvation history, beginning with the fact of sin bequeathed to the human race from the Fall, through the chosen people of Israel, through the Church founded by the Jew Jesus.

Zmirak here is reminding his readers that salvation of souls is the first thing for which the Church and its teaching and practices exist, often forgotten in an age where many inside and outside the Church assume it’s both a caucus for advancing secular policy goals and a club for a sort of group therapy in which people can have an opportunity to feel good about themselves.

From there, Zmirak in the second chapter deals with the episcopacy, from your friendly local Ordinary to the Pope, as bishops are the authentic teachers of the Faith. The title is,

“The Pope, the Other Bishops, and When and Why Catholics Have to Believe What They Say—and When They Don’t.” This chapter is the most important for the book, as it grounds Zmirak’s critiques of what many left-leaning clergy have asserted in recent decades. Zmirak herein affirms a certain magisterial minimalism:

There is just one thing that Catholics believe about every pope who legitimately held that title: not one has ever taught ex cathedra (“from the chair” of Peter) — that is, when he was making a solemn pronouncement of a dogma for the whole Church —anything on faith or morals that contradicts “the Deposit of Faith”. (p. 30)

Zmirak then flirts with conciliarism, noting that papal infallibility itself was affirmed by a council (Vatican I, 1870), and that “virtually everything that Christians share in common as points of faith was…arrived at as the decision of often contentious councils of bishops”

(p. 31), such as Christ’s equality of divinity with the father and Mary’s appellation as Mother of God.

Indeed, Zmirak is concerned that many contemporary Catholics see the pope as an “oracle”

(p. 39), whose words on economics and politics must be obeyed and cannot be challenged. Helpfully, Zmirak reminds his readers that the Holy Spirit does not directly choose popes (pp. 42–45, a point Cardinal Ratzinger also once made, with real force).

Zmirak notes that it’s actually Mormons who treat their president as an oracle who can declare heaven’s will directly and change doctrine on a dime, as with polygamy

(pp. 44–46). Positively, Zmirak explains the ordinary and extraordinary magisterium and what sort of obedience and assent is owed to each. The upshot for Zmirak is that

Catholics must obey (but have only to obey) authentic teaching on faith and morals. False teaching, however subtle, or clerical statements 0n (say) economics or politics outside the bounds of faith and morals, merit no necessary obedience.

Against “cafeteria Catholicism” and “Feeding Tube Catholicism,” then, Zmirak advocates for “Knife-and-Fork Catholicism.” Instead of picking what teachings we like in the cafeteria of faith and morals or lying back “as the latest pope’s latest statements are downloaded into our brains” as if (here mixing metaphors) hooked up to a feeding tube, Zmirak would have us “sit up like men and women with knives and forks at a restaurant,” accepting “balanced, healthful meals sent out by a chef whom we trust”

(p. 50).

“But,” he continues, “if there seems to be some kind of mistake,” like the serving of “prison rations,” then “we drop our forks” (p. 50). “We send the chef a message that we will pass, in the happy faith that the restaurant’s Owner will agree and understand” (p. 50). We are to side with Our Lord against his unfaithful shepherds.

This, here, is the key issue of Zmirak’s book:

Under what conditions do ordinary, faithful Catholics get to reject what some ecclesial authority asserts, from their parish priest to the pope?

Zmirak’s model requires faithful Catholics to know ecclesial documents backwards and forwards and assumes a high place for sanctified reason — that is, it presumes that Catholics have the ability to know the Faith and sift and sort contemporary pronouncements by it.

The Church issues official documents - conciliar constitutions, apostolic exhortations, encyclicals, dicasterial directives, catechisms, and so on — and publishes them in myriad languages in many media, from traditional booklets to the Web, because the Church esteems reason. It believes Catholics can read, understand, interpret, and apply them.

But a problem arises when thinking Catholics of whatever stripe interpret them in a way that seems to others at odds with what a document says, or simply rejects them because they seem to err in facts of morality or history or seem to contradict prior binding teaching. And so progressives reject

Humanae Vitae because it supposedly relies on an outmoded and insufficient conception of natural law, most Catholic biblical scholars reject what the Church really teaches about the authorship of many books of the Bible, and Amoris Laetitia gets interpreted and implemented in radically different ways in different dioceses and parishes. What’s a Catholic to do? Zmirak would have them think for themselves as informed and faithful Catholics, and if they do so, they’ll agree with him.

Having established the basics of Catholicism and how magisterial authority is supposed to work within, Zmirak moves both to hot-button issues and how progressives on one side and orthodox and traditionalist Catholics on the other have operated since the Council. Zmirak rightly emphasizes that

the “Spirit of Vatican II” is a nebulous, even Gnostic concept that allows its advocates the sole role of determining what the Spirit is saying, often in spite of the explicit statements of the conciliar documents, and argues convincingly that the texts of the council are normative.

In one of the best chapters in the book, “How Birth Control Tore the Church Apart,” Zmirak does an admirable job summarizing the context and aftermath of

Humanae Vitae, explaining how modern medicine and urbanization (thanks to which children became an economic burden more than an asset) made possible a reconsideration of the Church’s historic teaching on contraception.

Zmirak also notes that Pius XII made a “theological development” in 1951 in a speech to Italian midwives by asserting that limiting and spacing births was legitimate by means of periodic abstinence. But by the time of the Second Vatican Council, many leading laity and clergy were in the fevered grip of the ideology of technological progress and so rejected

Humanae Vitae absolutely.

Issued fifty years ago this month, it served to unmask the fissures simmering during and before the Council, making public and unavoidable a rift between progressive Catholics on one side of the divide and orthodox and traditionalist Catholics on the other.

As progressives came to dominate the conversation as well as chanceries and institutions in the West, the orthodox (associated later with John Paul II, who sought to receive the Council and implement it rightly) and traditionalists (who largely rejected the Council and joined splinter groups like the SSPX) retreated into subcultures.

Zmirak observes that progressivism became an exercise in autophagy [self-consumption], as the Church and its institutions have withered under their reign. Vocations have plummeted, and measures of fidelity among the laity indicate collapse. The orthodox and traditionalists persisted in maintaining a certain fidelity to the Faith, but have been ineffective in seizing real control of the Church.

Zmirak here is ecumenical in a way, calling the orthodox and traditionalists to get along and work together, whatever they make of John Paul’s actions and legacy, the state of the liturgy, and other items on which they might disagree.

As he does often in the book, Zmirak also reminds his readers that we need the other ninety-five percent of Catholics who reject Church teaching or don’t go to Mass because they simply don’t know any better

(see pp. 119–120): instead of writing them off or retreating to the righteous enclave of a subculture, Zmirak would have faithful Catholics see them as objects of gentle mission.

From here Zmirak moves on to hot-button political issues, such as economics, amnesty for illegal immigrants, gun rights and capital punishment, climate change, and sex. Whereas much of the Church’s clerical and lay leadership leans left on these issues, Zmirak contends that right-wing positions are compatible with Catholicism.

The Church, he thinks, has approved of market economics from the Middle Ages to today, and Zmirak accuses Francis and others of launching “straw-man” bromides against capitalism and economic freedom. Amnesty for illegals, Zmirak argues, will empower leftist politics in the United States and thus lead to ever more abortion.

Zmirak finds that Catholic calls for gun control are ill-informed and at real odds with Catholic teaching regarding the right of self-defense. So too with calls to abolish capital punishment; this of course is the most obviously problematic case for the so-called “development of doctrine,” as there was a papal executioner until 1870 and capital punishment remained on the Vatican City State’s legal books until 1969

(see p. 194).

As regards climate change, Zmirak reminds us that

the Church and its magisterium can pronounce definitively only on faith and morals, not matters of science. In the penultimate chapter, “Sex, Sanity, and the Catholic Church,” Zmirak describes the carnage left by the sexual revolution and shows in contrast how perennial Catholic teaching on marriage, sex, and family is sane and humane.

But he also decries how contemporary progressive Catholics —including, for him, Pope Francis — are seeking to undermine perennial teaching under the banner of a supposedly “pastoral” approach, rehearsing the drama surrounding the synods on the family and Amoris Laetitia.

Zmirak offers his own five-point plan to “make us prophetic witnesses to the reality of marriage, in the face of the pale pansexual temporary sex contract that our laws call by that name”

(pp. 282–283). The plan includes NFP training, a “covenant” binding Catholics to Catholic teaching (lifelong marriage; a renunciation of divorce and remarriage, and an agreement that the aggrieved party gets all common property in the case of a civil divorce); the making of a civil divorce a result of an annulment, not a prerequisite; strict application of canon law; and a waiting period of three to five years for marriage after annulment.

Zmirak closes the book with a chapter dealing with “Temptations and Opportunities for the Church.” For Zmirak, the temptation is retreat: either a retreat into progressivism (he names several prominent, supposedly orthodox Catholics active on the internet who in his view have given in), or a retreat into righteous enclaves.

In Zmirak’s view a “seamless garment” approach to life issues will dilute prolife witness and activism on the fundamental crime of procured abortion (see also prior in the book, pages 96–101), while he also fears blessing gay couples is a real possibility in the near future, as is surrendering our fight for political freedom as citizens and religious liberty as churchmen.

In all these areas, certain progressives would have us surrender to the Spirit of the Age (which, I observe, is what ecclesial progressivism is designed to do, as it attempts to progress to the ends determined by liberal modernity, and thus seeks to employ the Church as a caucus supporting the standard laundry list of left-wing causes favored by Western elites).

Along the way here Zmirak wrongly derides Rod Dreher’s “Benedict Option” as defeatist retreatism, which Zmirak, and most reviewers of Dreher’s work, misunderstand —

Dreher is calling for traditional Christians to realize they’re on the margins on the West and to focus on developing thick communities devoted to Christian practices like liturgical prayer, mutual support, and hospitality while still evangelizing and fighting tooth and nail for religious liberty.

Zmirak ends by endorsing Jason Scott Jones’ “Whole Life” program which he himself modified with Jones in

The Race to Save Our Century (Crossroad, 2014), and which is presented in the present work as a five-point list of fundamental principles (see pp. 325–326):

- The sanctity of each human being as an image of God

- The reality of a transcendent moral order that is above all man-made laws

- The need for a free society that protects fundamental rights

- The virtues of a humane economy that allows humans to flourish

- The duty of solidarity among every member of the human family

Zmirak is an entertaining writer, by turns witty, by turns acerbic, and always clear. For those looking for a representative model of how certain Catholics disagree with clerics and remain faithful, this book serves as a ready, readable resource.

But it’s perhaps also idiosyncratic to the point of being Quixotic; has Zmirak made himself a one-man magisterium? Is his sort of political conservatism, which looks so traditionally American, if not libertarian, really what the Church affirms? Zmirak would say yes, of course, and he can point to myriad moments in history and official documents to make his case.

Above all his work shows up the crisis in contemporary Catholicism, in which the post-conciliar Church seems to many to be estranged from the Church of prior eras. Whether one follows him will depend on just how confident one is in one’s own knowledge and reason in judging contemporary clerical pronouncements. But perhaps that’s precisely the sort of laity that Vatican II envisioned.

Dr. Leroy Huizenga is Administrative Chair of Human and Divine Sciences at the University of Mary in Bismarck, N.D. Dr. Huizenga has a B.A. in Religion from Jamestown College (N.D.), a Master of Divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary, and a Ph.D. in New Testament from Duke University. During his doctoral studies he received a Fulbright Grant to study and teach at Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt, Germany. After teaching at Wheaton College (Ill.) for five years, Dr. Huizenga was reconciled with the Catholic Church at the Easter Vigil of 2011. Dr. Huizenga is the author of The New Isaac: Tradition and Intertextuality in the Gospel of Matthew and co-editor of Reading the Bible Intertextually.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 21/07/2018 23:04]