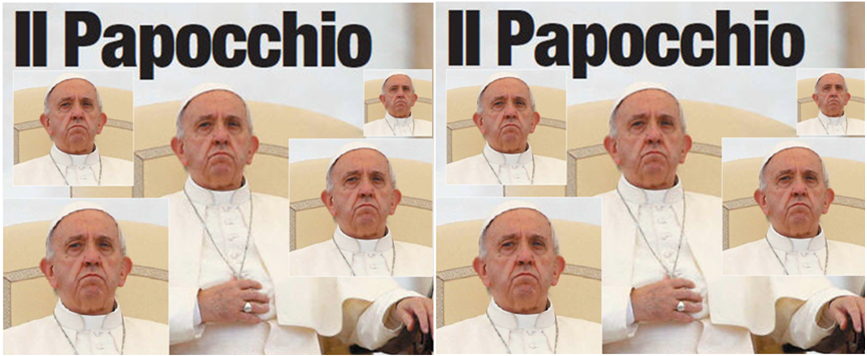

Papocchio is not, as one might think, a pejorative form of 'Papa', but an Italian word that means imbroglio, deception, or dupery, all of which would describe some major aspect of the Bergoglio pontificate.

As Jorge Bergoglio nears completion of five years as pope, here is a critique that is mostly unflinching but nonetheless gives him credit for

Papocchio is not, as one might think, a pejorative form of 'Papa', but an Italian word that means imbroglio, deception, or dupery, all of which would describe some major aspect of the Bergoglio pontificate.

As Jorge Bergoglio nears completion of five years as pope, here is a critique that is mostly unflinching but nonetheless gives him credit for

advocating a church of the poor and merciful as though none of the other beatitudes were worth any attention... The writer is a professor of theology

at Canada's McGill University.

The Francis 'Reformation'

The question is not whether the Church is to be a Church of the poor and of the merciful.

Of course it is - but it's more than that. It ought to be a Church

of all the beatitudes.

by Douglas Farrow

February 28, 2018

On March 13, 2013, five hundred years and two days after the election of Pope Leo X, Cardinal Bergoglio was elected as the 266th occupant of St Peter’s throne. He took a novel papal name, Francis, and began (in his own words of advice to youth) “making a mess.”

Cleaning up the curia, which many thought his primary task, never quite got underway; or where it did get underway, didn’t get the papal support it required. There were innovations all right, but of a kind that drove the Church deeper into crisis, a moral and doctrinal crisis not unrelated to the one that overtook Leo’s pontificate.

Leo X’s crisis was already brewing when he came to office, yet he neglected it for lesser things, allowing it to boil over and flood Christendom with scalding liquids the disfiguring effects of which we are still witnessing.

Francis’s crisis was also brewing when he came to office, but he was put there by the machinations of men who wished to turn up the heat. That was done chiefly by way of the two synods on the family and the production of Amoris laetitia, with its notorious eighth chapter, which reintroduces the proportionalism identified by John Paul II as a major root of the crisis. This pot also threatens to boil over, as the posing of dubia and the almost unheard-of attempt at a correctio bear witness. Meanwhile, Francis has been playing a role more like Luther’s than Leo’s.

Francis is the pope. He is not nailing theses to church doors or challenging anyone to a debate. In fact, he refuses to render judgments on debated matters. But he is very much the charismatic, even autocratic, leader – criticizing, cajoling, throwing verbal faggots on the fire.

Moreover, in this time of confusion he seems to be searching, like Luther, for an answer to the question:

“How can I get a gracious God?” [An absurd question, to begin with! God is God, and we do not get to choose 'what kind of God' we want! Our belief in God, like our love for him, has to be total and unconditional, all or nothing!]

And, in that search, he does not shy from differing with magisterial tradition as regards faith and morals and the sacraments, though (unlike Luther) he presents these differences merely as new pastoral or missionary strategies. He has even found ways, through a synodical ecclesiology, to provide something close to de iure approval of de facto schisms in doctrine and discipline, effecting a Reformation-like turmoil in the Church. [[The pope is supposed to be the visible symbol of Church unity, but this pope revels in proactively, consciously and deliberately fostering disunity. "I am aware that someday I may be seen as someone who split the Church" - how can any pope worthy of the name and the office even dare to say that as Bergoglio has done?]

Now, it is not rare to hear from clergy and laity who support the Francis reformation, and even from Francis himself, that all this is a work of the Spirit that must not be challenged but faithfully, indeed irreversibly, pursued. This also sounds rather like Luther, both in style and in substance. It is language I find greatly disturbing.

- Does the Spirit make claims that are plainly contradictory (conscience is/is not the final arbiter in matters of sacramental discipline; adultery does/does not preclude a state of grace; capital punishment is/is not intrinsically evil; etc.)?

- Does the Spirit call for arrangements that will accommodate the sexual revolution?

- Does the Spirit set bishop against bishop?

- Speaking of bishops, does the Spirit first oppose, then propose, lay investiture or encourage “inculturation” by deposing faithful bishops in favour of quislings?

We need, I dare say, not only discernment of situation, but discernment of spirits. [And what isn't of the Holy Spirit, where the Church is concerned, is necessarily that of the anti-Spirit, Lucifer-Satan himself!]

Where shall we begin? Let us confess straight away that the Francis reformation has much to commend it, just as Luther’s did. A Church of the humble, a Church for the poor, a Church that goes out among the people, scouring the highways and byways to deliver unexpected invitations to the Great Feast, a Church that conveys the mercy of God to those most in need of it: such is the Church that is following its Lord. [Yes, but it is very deliberately selective. The Church is for all, not just the poor - and the only categories that matter, for the mission of the Church, are sinners who sincerely try to live up to the Lord's Gospel, and sinners who don't: the latter are the 'poor' who are most in need of the Church, not the materially poor.] Francis speaks to this, and tries to model it. Whether he speaks well or poorly, whether he models wisely and consistently, may be questioned, but not this basic fact. [The writer appears to completely ignore Bergoglio's self-servingly selective use (misuse/abuse) of the Gospel to promote his own agenda, which is largely political and social (and only incidentally, religious, because he is after all, the pope). Jesus is Truth himself, and to misrepresent his words by choosing and picking which of them to preach, is to violate the truth, and therefore, to blaspheme Jesus.]

And here we should take stock of his own background and agenda, not confusing it with the agendas of those whom we already knew and about which we already worried, though it is certainly disconcerting that Francis has drawn so many of the latter into his own confidence and into his administration of Church affairs.

Francis is rooted in his native Argentine teología del pueblo, which regards “popular religiosity” as a basic category. Taking his magisterial cue from the opening line of Gaudium et spes (of which he says, “here we find the basis for our dialogue with the contemporary world”), while worrying that the Church has lost the ninety-and-nine and must go in search of them, Francis desires a strategy for reconnection with the people. He rejects the restorationist program of traditionalists and seeks instead to cultivate in the Church “a real desire to respond, to change, to correspond” to the hopes and desires and sufferings of ordinary folk, in hopes of returning them to the fold. [That's a whole load of bullshit! He's not seeking to return anyone to the fold! He keeps saying "God accepts you as you are - you don't have to do anything" and "I'm not asking anyone to be Catholic"! And the only 'reconnection' he's interested in is the sort of celebrityhood that he already enjoys in over-abundance!]

This does not adequately account, however, for the most troubling features of his papacy, which Thomas Weinandy recounted in his letter to Francis of 31 July 2017, elaborated soon after by the pseudonymous author of Il Papa Dittatore.

One that Fr Weinandy does not mention is Francis’s deliberate distancing from St John Paul II, a man whose credentials for suffering with the people and whose capacity to rekindle faith among them far outstrip his own. [Perhaps Fr Weinandy does not say so in those words, but like all the well-meaning critics of AL, he surely underscores how AL alone, by itself, tramples down on the Polish pope-saint's Familiaris consortio and Veritatis splendor!]

How shall we explain that distancing, if not by his embrace of what Keith Lemna and David Delaney, in “Three Pathways into the Theological Mind of Pope Francis”, referred to as the “post-conciliar strategy to inculturate the gospel to modern tastes that was adopted by so many of his Jesuit confreres after the Second Vatican Council”?

Against John Paul II, Francis has clearly partnered himself with those who think it time “for the Church to seek a mediatory pact with contemporary secular culture” by bracketing out “contentious social disputes that appear to be peculiarly Christian concerns” – who indeed believe this “an indispensable first stage in the journey to reach the lost ninety-nine.” [Aw, shut up already about Bergoglio seeking to 'reach the lost' 99 or whatever! Besides, I thought the Biblical story was about 1 lost sheep that the shepherd goes out to seek - not 99 lost sheep (what, they all scattered to the four winds?), though with Bergoglio, 'the unfaithful shepherd', as Phil Lawler calls him in his book, the lost sheep are certainly far more than just one!]

Not only has he appointed such people to high office, despite in some cases their sexual or financial misbehaviour; he has worked with them to subvert the dicasteries and institutes that were carrying forward John Paul II’s agenda, while marginalizing the doctrinal oversight of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Even when we try to isolate the Bergoglian agenda from its European or American attachments, then, we run into trouble. That God regularly invites the Church to a fresh inculturation of its mission is not to be doubted, whatever the merits or demerits of the teología del pueblo and the Aparecida document (surely Bergoglio’s finest work) [Oh, that is such a disputable statement on many levels I shall not even begin to say how. Suffice it to say that it certainly has had no effect at all on re-evangelizing Latin America, and that since Aparecida, the Church in Latin America has continued to hemorrhage members unabated!] as a model for our time.

Yet the Francis reformation, as a call to go out among the poor and needy [Does he really believe he is the first pope ever to have made such a call? As if the Church, especially from the 20th century onwards, had not been the single institution that most consistently and widely provided health, education and welfare services globally to the neediest regardless of race or religion!], does not break much new missionary ground.

It is not that call that is generating a crisis in the Church, but rather the call for another kind of accompaniment, the call for an exercise of “mercy” that echoes Jesus in John 8 but somehow neglects his “Go, and sin no more” – the call that neglects halakah, that puts doctrine and discipline aside, that makes the rich and comfortable still more comfortable while doing little to challenge popular religiosity with the demands of authentic discipleship. Here “rules and prohibitions” and “the repetition of doctrinal principals” (Aparecida 12) are not thought to be insufficient, as indeed they are, so much as to be impediments, which they are not.

We will not get far, in this business of discernment, by asking whether the Church is to be a Church of the poor and a Church of the merciful. Of course it is. We must ask instead whether it is to be a Church of all the beatitudes.

The Francis reformation places emphasis on the fifth – “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy” – but sometimes seems ambivalent about the fourth and the sixth: “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness… Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.” It stresses the first, in its Lukan version – “Blessed are the poor” – but has little to say about the last two: “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake… Blessed are you when men revile you…”

And why is that? Not because of the preeminence of divine mercy, already emphasized by John Paul II in Dives in misericordia, but because of its tendency to oppose mercy and justice, despite Francis’s own statements in Misericordiae vultus that they cannot be opposed. [But one can and must know right away from the statements Bergoglio makes pro forma - he is the pope and there are certain things he must pay lip service to - without meaning any of it!]

That tendency, we may be confident, has much to do with the Humanae vitae rebellion and indeed with a determination to adopt something like the modern Protestant attitude towards sex and marriage, as R. R. Reno has trenchantly observed in “Bourgeois Religion.” With Francis himself things may be otherwise; but, if so, he is closing his eyes to a great deal of what is going on around him.

At all events, his constant railing against the evils of “rigidity” suggest that he has imbibed more than a little of what Augusto Del Noce characterized in The Crisis of Modernity as “a critique of authority in the name of conscience, or in the name of a historical process thought to be providential and irreversible because willed by God, a process which eliminates every ‘fixism.’”

Consider here the four principles of good governance he adopted many decades ago and, without warrant from scripture or tradition has introduced into his magisterial writings. Claudio Remeseira, leaning on Bergolio’s fellow Jesuit, Juan Carlos Scannone, tells us that these principles – “Time is greater than space; Unity prevails over conflict; Realities are more important than ideas; The whole is greater than the part” – were extrapolated from a letter written in 1835 by Juan Manuel de Rosas to Facundo Quiroga during the Argentine constitutional controversy. [I cannot believe anyone can seriously take such incoherent statements for principles that hold together! Five years ago, when I first came across them, I scoffed at them one by one as a risible attempt to sound 'profound'. And how, pray, does Bergoglio abide at all by his maxim "Unity prevails over conflict"?] They are “constantly invoked by Francis and constitute the mainstay of the fourth chapter” of Evangelii gaudium.

The first of them invites Francis to dismiss those “nostalgic” elements in the Church that remain stuck in the past and are unwilling to let tradition evolve. The second, we may add, recalling as it does the Teilhardian maxim that “incoherence is the prelude to unification,” underlies his advice to make a mess [And how does that fit into the role of the pope as the visible symbol of unity in the Church?]; while the third and fourth also relativize fixed notions and established practices to the needs of the present moment.

Remeseira stresses Francis’s capacity to combine progressivism with an anti-modernist note. “Many people still wonder whether he is a true progressive or a conservative camouflaged with soundbites and gestures that please the liberal crowds but that in the end have little or no consequence for the real life of the Church. The truth is that he is a little bit of both.”

His thinking proceeds like a fugue, as he wrestles with the “unresolved conflict at the heart of Catholicism,” even Vatican II Catholicism; namely, how to proclaim Christ in a relentlessly secularist age.

“When Francis says that he is nobody to judge a gay person, or when he asks forgiveness for the crimes committed by the Church during the so-called Conquest of the New World, or when he forfeits excommunication to women who had had an abortion, he is playing the liberal voice; it is the progressive line singing. When he ratifies the Vatican’s traditional teaching on contraception, priest celibacy, same-sex marriage and female priesthood, [Who really knows if he means his lip service against all these things, when there is no lack of indications to show that he is really 'soft' on these issues the rare times that he brings them up?] it is the conservative voice that comes up front. The important thing to keep in mind is that, as in counterpoint – a fugue’s central device – both voices are playing at the same time, only at different parts of the score.” [But counterpoint in music is harmonious. Bergoglio's doublespeak is simply and offensively discordant.]

But, leaving aside the fact that Francis’s mind does not seem anything like as tidy as a fugue, we must insist that this putative conflict at the heart of Catholicism, which is really a conflict between the Church and the world, cannot be resolved by some ad hoc human counterpoint.

Rather, it has already been resolved by the divine counterpoint in the cross and resurrection, the ascension and anticipated parousia, of Jesus Christ. That divine counterpoint instructs us to be very careful with inculturation, and to expect in the present age progress in evil as in good. This, surely, Francis knows. Yet he should also know, and apparently does not, that the divine counterpoint does not justify his maxims or their elevation into theological principles.

According to Evangelii gaudium, “a constant tension exists between fullness and limitation.” Fullness “evokes the desire for complete possession, while limitation is a wall set before us.” Time is greater than space in the sense that it breaks down this wall. It is a constant opening, says Francis, for we live “poised between each individual moment and the greater, brighter horizon of the utopian future as the final cause which draws us to itself.” Knowledge that time is greater than space “enables us to work slowly but surely, without being obsessed with immediate results” or anxieties about “inevitable changes in our plans.” [All nonsense, because whatever is accomplished in time requires space to accomplish it in! That should be evident to anyone, even if you are ignorant of the space-time continuum that is the reality of the physical world. What happens in time does not happen in a void!]

“Giving priority to space,” on the other hand, “means madly attempting to keep everything together in the present, trying to possess all the spaces of power and of self-assertion.” Time ought to govern spaces, for it “illumines them and makes them links in a constantly expanding chain, with no possibility of return. What we need, then, is to give priority to actions which generate new processes in society and engage other persons and groups who can develop them to the point where they bear fruit in significant historical events.”

This construct, I fear, is [ALL NONSENSE] not governed by the gospel or by the Eucharist. It intrudes as a foreign element that owes far more to Lessing and Hegel and the process theologians than Francis seems to realize.

Are we to adopt the Teilhardian slogan – one notes that the cry has gone up for Teilhard’s rehabilitation – L’En Haut et l’En Avant? Is it to be upwards and onwards, onwards and upwards? Then we must indeed dispense with every “fixism,” including even the fixing of Jesus to his cross and of the Church to the via crucis. Or (which comes to the same thing) we must reinterpret the cross as representing “the deepest aspirations of our age.” [What???? Bergoglio's 'church of nice' would do away with the Cross if it could! Oh no! No one must suffer anything, not even for their sins which Bergoglio effectively considers not sins any more or at all! Everything ought to be convenient and comfortable. And shut up about Hell and the Last Judgment! None of those 'terrors' must afflict the Bergoglian!]

Perhaps, if time really is greater than space, we may dispense also, as Luther did, with the Apostolic See itself? The step to Santa Marta is a step towards the walls, and Francis rightly wants the Church to go out beyond its walls into the highways and byways. [But is that not what she has been doing all these centuries through her missionary work around the globe? A mission that Bergoglio appears to have dropped because he thinks it is unnecessary - he doesn't want to make anyone Catholic, they are fine just as they are where they are.]

Yet the bones of Peter testify to the fact that the Church can only call people back to the future; that it can only call them to a very specific place and moment, as witnesses of the passion and the resurrection. It can only call them to a centre already fixed by God in space and time. That is what is “irreversible,” not some fancied progress in forging an ever-expanding chain of “significant historical events” or growing a “universal human consciousness” (Veritatis gaudium 4).

But let us allow that Francis is not a typical progressivist and press on with our attempt at discernment by recalling that one fixture of Catholic moral teaching that is already threatened by the desire to get outside the walls and beyond the past is the sixth commandment.

Unless adultery is not always adultery, it seems that adultery is not always wrong – or so many have concluded from Amoris, a conclusion blessed by Francis in the letter now ensconced in the Acta Apostolica Sedis. To put it a bit more accurately, adultery is always adultery and objectively wrong, but the person committing adultery may not be gravely culpable and may even be doing what God is asking of them.

Happily, this falsehood, which rests on an untenable notion of (subjectively) sinnerless sins and amounts to a form of situation ethics, does not touch as yet the infallibility doctrine; for nothing Francis has written or said meets the conditions of that doctrine, [That may be so, but he does not think that! He may not directly qualify his preaching as 'infallible' but the vigor with which he asserts them insistently, blasphemously invoking the Holy Spirit speaking through him, implies something more far-reaching: i.e., he would seem to imply that he is receiving'revelation' from the Holy Spirit, even if the Church postulates that 'revelation' ended with the Apostles] whether as stated by the First Vatican Council or as elaborated in Bishop Gasser’s relatio.

That is not to say that it can be tolerated or left unresolved, however, since it touches directly on dominical authority, on the moral order, and on the integrity of the gospel and the sacraments.

About all this so much has been said that one hardly knows where to begin. To confine ourselves to its impact on the Eucharist, the pope, it appears, is determined to treat that sacrament as what some among the Methodists and the Reformed call a converting ordinance; that is, as something that can be approached with the intention of enhancing faith, without too many inhibitions arising from consideration of one’s actual state of life or fitness for the sacrament – which, to be sure, is never anything other or less than medicine for the sick.

Though the Catholic Church does not deny what John Wesley chiefly meant by the expression “converting ordinance” (viz., that the sacrament is not a reward for perfect faith and holiness but a means of grace intended to nourish all the faithful), it does deny – or has until now – the use made of that idea among those who have argued for open communion. Francis, however, is making a mess by pushing for a limited form of open communion. And, if open here, why not there? If open to these (the divorced living more uxorio in a civil marriage or perhaps no marriage at all), why not also to those (make your proposal)? If we are not to discipline the one, why discipline the other? [Perhaps because he deliberately wishes for everyone to go down the slippery slope of his laissez-faire pastoral principle - 'Do as you please and do not worry, God is infinitely merciful!']

Our present lax attitude to discipline – discipline also is medicine for the sick – can hardly be put down to Francis. It has been with us since the temporary truce over Humanae vitae, and many bishops and priests have de facto permitted a kind of open communion.

But Francis is pope, and if his established teaching on the matter does not square with tradition, tradition itself can no longer be conceived in any distinctly Catholic way.

Moreover, it is not possible (as Veritatis makes clear) to isolate this “purely pastoral” matter from moral and doctrinal matters, such as Catholic teaching on the conscience and intrinsic evil, or on the unconditional grace of God in Jesus Christ.

If marital obligations are revocable, either marriage ceases to be a sacrament or that of which it is a sacrament is also revocable. If adultery is not a barrier to communion, then communion itself is something other than what the Church says it is.

The prayer of the Church governs the faith of the Church and the faith of the Church governs its pastoral practice. The moment this relation is reversed, we set foot on the same road Luther and his fellow reformers trod.

“How can we get a gracious God?” is the wrong question to ask [because it is inherently absurd!]. The right question is how we can be true to the grace of God that has already appeared for the salvation of all men; and the right answer is that we must allow it to train us “to renounce irreligion and worldly passions, and to live sober, upright, and godly lives in this world, awaiting our blessed hope” (Tit. 2:12f.).

Now, whatever conclusions are reached about Francis – who, like Luther, seems by turns gentle and angry, transparent and inscrutable, clear and confused – it must not be overlooked that his pontificate comes at a time in which the contrary spirit that has been abroad in the Church for nearly a millennium has grown very bold.

The spirit of the nominalists who gave birth to skepticism, the spirit that reared its head in the Reformation to fracture rather than to unite, the spirit that has had to be dealt with again and again in ever more dangerous ideological iterations – the spirit of lawlessness rebuked in Veritatis splendor– now walks where it wills, even in the halls of the Vatican, and that by papal invitation. Though it has not, or not yet, stretched out its hands for the prize of some de fide proclamation, it has already begun to parlay with the Rock.

With the Rock? With Peter confessing Christ? Surely not, some say; but perhaps they are forgetting Jesus’s own temptation, and his remarkable rebuke to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan!”

I recall being told by a senior churchman not long ago that it is dangerous to challenge the charism of a pope. That no doubt is true, but it is still more dangerous to let a pope pursue a false course. Besides, it begs the question as to what is and what is not a proper papal charism.

That popes have a charism beyond the mandate and promises given to Peter and his successors, that they have a charism peculiar to their own pontificate, is not a matter of doctrine; nor does it stand the test of history. Some popes served so briefly as to leave no discernible mark at all, while others left the Church in a much worse state than they found it. In any event, the notion that popes are always true to such additional charisms as they may have is quite obviously false.

At Vatican I, it was not claimed that popes have a peculiar charism, or any guarantee of personal faithfulness to their ex officio Petrine charism. It was claimed only that they do have the Petrine charism and that Providence would prevent their violation of it in formal acts of judgment on matters of faith and morals.

While St Bellarmine, as Bishop Gasser pointed out, had in his day ventured qualified support for Pighius’s “pious and probable” theory that, even as a particular person, a pope could never pertinaciously believe something contrary to the faith, the Vatican fathers did not so venture. Personally, I think this pious speculation very much less than probable. Pious speculation might also posit that there will be no popes in hell, but pondering Dante provides a cure for that.

To resist the task of discerning spirits on the assumption that no pope, even when not acting ex cathedra, would ever confuse or suppress the truth doctrinally, despite an abundance of evidence that he might do so morally, requires a much higher view of the papacy than is warranted by any judgment of the Church.

It also requires a blind eye to the contradictions that made their way into Amoris, contradictions that correspond to – and provide openings for – significant changes being effected on the ground. And, on the principle that reality is greater than ideas, there is every reason to suppose that these changes on the ground presage a still more concerted attempt to bring about doctrinal changes, changes that would bring the magisterium into self-contradiction. The “protestantization” of the Catholic Church would then be complete.

The present situation, thankfully, is not so dire as that. There is even something salutary about it, for it exposes those who are inclined to put their trust in popes, rather than in God and his Christ.

On the Feast of the Chair of St Peter in 2005, one enthusiastic priest wrote: “Can a Catholic dissent from the Papal Magisterium and still claim to be a Catholic in good standing? Can one refuse to render a ‘religious submission of mind and will’ to the Pope’s teachings? No! Absolutely not! … Catholics must obey the teachings of the Pope both from his Ordinary and his Extra-Ordinary Magisterium. Too often, I believe, the mistake is made of restricting the infallible teaching charism of the Holy Father exclusively to the ex cathedra forum. Dissident theologians have capitalized on this misinterpretation, leading many Catholics to believe that they are bound to follow only the de fide or ex cathedra teachings of the Roman Pontiff. This limitation was never the mind of the Church. It certainly was not the mind of the Fathers either of Vatican I or Vatican II.” I wonder what this priest would say now, were he still with us.

Benedict himself, when he took up that Chair, was far more clear-sighted:

“The power that Christ conferred upon Peter and his Successors is, in an absolute sense, a mandate to serve. The power of teaching in the Church involves a commitment to the service of obedience to the faith. The Pope is not an absolute monarch whose thoughts and desires are law. On the contrary, the Pope’s ministry is a guarantee of obedience to Christ and to his Word. He must not proclaim his own ideas, but rather constantly bind himself and the Church to obedience to God’s Word, in the face of every attempt to adapt it or water it down, and every form of opportunism.”

And where this commitment or guarantee is not made good on, what then? Many years earlier – sounding a bit like John Henry Newman, whose “minimist” view of infallibility commends itself as a prudent one – Cardinal Ratzinger warned that “criticism of papal pronouncements will be possible and even necessary, to the extent that they lack support in Scripture and the Creed, that is, in the faith of the whole Church.”

Well, now we are faced with just that necessity, thanks in part to his own decision to resign. We are faced in his successor with one who (if this exercise in discernment has not utterly failed) is compromising the faith and sacraments and unity of the Church.

We shall have to deal with that, not by doubling down on papolatry, but by ridding ourselves of it. Not by trying to save the appearances of things Francis says or does – what could that accomplish, other than to justify the Protestant view of Catholicism? – but by reckoning with them quite honestly and repudiating them where holy tradition demands they be repudiated.

And this cannot be a matter of every man for himself. It is a task ultimately for the bishops, divided as they are, and especially for the Sacred College, for all share the pontiff’s sacred duty to defend the faith.

But how then can it be said, cum Petro et sub Petro? How can it be insisted, “never apart from this head”? Will the church in Rome, with the blessing of the Bishop of Rome, be among those that deviate from the historic doctrine and discipline of the holy Catholic Church? Will Rome no longer be that church, of all the churches, to which (in Gasser’s words) “faithlessness has no access and with which, because of its more powerful primacy, every church must agree”? Will Rome itself (despite Cardinal Vallini’s admirable caution) have to be corrected?

Cum Petro et sub Petro: substitute aut for et and the crisis of which we have been speaking comes into focus. If it is not yet dire, it is certainly urgent. For Peter is divided from Peter, not as anti-popes are divided from the legitimate pope, whose office they covet, but as a successor from his predecessors. [Typically Bergoglian! If he thinks he would have been 'merciful' with Adam and Eve and not driven them out of Eden as God did, and if he thinks he knows better than Christ and the Apostles what the Church ought to be, how much easier for him to think he knows better than any of his predecessors as pope!]

It does not seem possible to follow Francis obediently and to remain at the same time with his predecessors – whether his recent predecessors, whose work he has systematically undermined, or his predecessors taken as a whole. It does not seem possible to follow Francis and remain within the boundaries of faith marked out by the Fathers of Trent, who had to defend from attack the very same sacraments that are threatened again today even in Rome itself.

No response that fails to escape the horns of this dilemma can hope to be successful. Rome must be corrected, yes, but it must be corrected by Rome. Peter must be corrected, but corrected in the time-honoured fashion by Paul.

- Which is to say: those in the college of bishops, in concert with those in the cardinalate who recognize what is at stake in this crisis and are prepared to act, must confront Peter in private and try to win their brother.

- If they are unsuccessful, they must oppose him to his face, before the church in Rome, demonstrating that he “stands condemned” by his own actions.

- Moreover, they must see to it that the church in Rome, to which the cardinal electors (though an international body) are de iure related, fully participates in this process.

Now, it will be pointed out that there is no canonical process for passing judgment on a pope; indeed, that there is no earthly court in which such judgment can be passed. To which two responses may be made:

- First, the process of which we are speaking is not a juridical one, and could never become such without a change in canon law. A pope can resign, but he cannot be removed from office by his brethren; he can only be removed “by the law itself” (canon 194), that is, by reason of having “publicly defected from the Catholic faith or from the communion of the Church.”

- Second, if the process, which is a personal and collegial one, were unsuccessful at its private stage, it would likely lead either to resignation or to the appearance of some formal heresy that would bring canon 194 into play. That this, or some still sadder or more troubling outcome, can be imagined is no reason for refusing the Pauline duty, to shirk which is to leave the faith itself at risk.

I have said that the immediate task of correcting particular errors on the part of Francis, errors which do not yet amount to heresy, and the larger task of rethinking the papal role as such and determining what good governance in today’s Church really means, must be undertaken by willing bishops and cardinals, acting in concert. [Which all sounds excellent in theory. But the fact that there are so few cardinals and bishops who have dared to publicly criticize this pope for his anti-Catholic word and deeds surely tells us there are not enough of them to be 'significant' in terms of achieving anything concrete. Ten or so cardinals and bishops constitute a pitiable fraction of the world's 5000-plus bishops and 200-plus cardinals!]

Neither of these tasks, however, whether they prove surprisingly simple in execution or difficult and protracted, should be allowed to obscure the fact that the Church as a whole is being asked to choose between two very different paths: the Protestant path that leads to individualism and sectarianism and thence, as the past half-millennium has shown, to cultural assimilation and statism; or the path that leads to a more authentic Catholicism that is both traditional and evangelical, unified and missionary – a communio Catholicism from which the contrary spirit has been fully exorcised.

It is for the sake of this choice, I believe, that an otherwise calamitous pontificate has been permitted. As Fr Weinandy put it at the end of his letter to Francis, perhaps our Lord does indeed want “to manifest just how weak is the faith of many within the Church, including many of her bishops.

“Ironically,” he adds, “your pontificate has given those who hold harmful theological and pastoral views the license and confidence to come into the light and expose their previously hidden darkness. In recognizing this darkness, the Church will humbly need to renew herself, and so continue to grow in holiness.”

Is that not a sound discernment? There are corrupt things in the Church that have been crawling slowly but surely into view, surviving even the harsh light cast on some of them in 2002 – old things that have been growing in the shadows for a very long time, fed by the spirit of lawlessness and recognizable as rebellion against the law of Christ, even when disguised as mercy and compassion or inculturation and accommodation.

Since the Church cannot renew herself by herself, but can and will be renewed by the Spirit of God, let us pray for our bishops, especially the Bishop of Rome, that they may name these things accurately and put them to flight.

I find the following commentary an appropriate postscript to the above:

Your Church, no matter what

March 1, 2018

The situation is, admittedly, dire. However, fleeing to a parallel reality is not the solution.

There is only one Church, and this is the deal we get. There is only one Pope (in charge, I mean) and that one is the guy we get.

The Church has gone through horrible crises and periods of extreme corruption before. This is clearly the worst crisis ever, but again we were never promised that we would never see a worse crisis than those the Church experienced in the past.

Also, in the bimillenarian history of the Church there had never been a period of defiance of Church teaching from within. Is it so surprising that the subsequent Divine Punishment would affect the Church also from within?

This is still your Church. It is covered in mud, but below the thick strata of Vatican II dirt it is as resplendent as ever. We are all expected to stay faithful to her, no matter how thick the mud; because, like Padre Pio, we love the Church even if she kills us.

It is the lot given to us to live in a time of heresy. But the Church will never be that heresy. We refuse obedience to a heretical Pope in everything in which obedience is not due to him. But we do not break our link to Christ’s Church.

We do not decide who is Pope. We do not decide whether the Church exists. Much less we decide whether she “deserves us”.

We accept this dire situation as, at the same time, our lot and our task. We accept that we might not have the consolation, on our deathbed, of knowing that the once great crisis has been overcome. We prepare ourselves to die in fidelity to that resplendent Church lying below the thick strata of mud, and we keep giving our allegiance to it.

You did not give up your passport when Obama became president. You do not give up on the Church when the Pope is a damn atheist, heretical Commie.

Don’t be a “not my President”-type Catholic.

To paraphrase Winston Churchill, “it’s the only Church you have”.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 01/03/2018 12:53]