For alerting me to this excellent article, thanks to Lella and her blog followers at

JESUS is a monthly magazine of Edizioni San Paolo, which also publishes FAMIGLIA CRISTIANA. The illustrations came with the article.

Atheism and Christianity

JESUS is a monthly magazine of Edizioni San Paolo, which also publishes FAMIGLIA CRISTIANA. The illustrations came with the article.

Atheism and Christianity

by Mons. Gianfranco Ravasi

President of the Pontifical Council for Culture

Translated from

August 2009 issue

From the Biblical point of view, there are different kinds of atheism: there is disbelief, which is similar to religious indifference; there is idolatry; and finally, there is the consciousness of God's absence, the spiritual void suffered by those who are really in search of a religious horizon and desirous of the truth.

"Fall to your knees! The bell is ringing - they are bringing the Sacraments to a dying God!" This was the 19th-century German poet Heinrich Heine's paradoxical way to express the imminent 'death of God', which was subsequently described far more dramatically by his fellow German and contemporary Friedrich Nietzsche, in his famous scene of Gaia-science, in which a man runs through the streets crying out in wild tones: "God is dead! We have killed him and our hands are dripping with his blood!"

Well, this type of hyperdramatic atheism - which gave rise to a 'theology of the death of God' - has almost disappeared completely. What survives of atheism today are the sarcastic mockeries by the atheists du jour, the Odifreddis, Onfrays and Hitchenses, to name them by their linguistic areas of influence.

[Piergiorgio Odifreddi is an Italian mathematician who has written best-selling anti-God, anti-religion books; Michel Onfray is a French philosopher who wrote a 2005 book against the major religions translated into English as The Atheist Manifesto; and Hitchens is an iconoclastic journalist who wrote God is not great

To confront the problem of atheism from the Biblical point of view may paradoxically be of great relevance, even if at first glance, the theme would seem to be absent in Sacred Scripture, since in the ancient cultures, the absolute denial of God was almost unthinkable.

In fact, the profound spirit of atheism, in all its forms, appears within the Bible in serious, well-articulated ways, and treated according to the aforementioned categories.

First, disbelief, simply not believing - denying the presence of God in history and therefore, a refusal to accept any transcendent ethical norms, much less the idea of God's will.

Such is the well-known cry by the 'fool' in Psalm 14,53: "There is no God". The sense of the statement is not a theoretical, programmatic denial but rather the disconcerted discovery that there is no divine presence to respect and to fear, here and now, in human history.

This attitude is also expressed in the Bible with the verb 'to murmur', which is on the mouth of the people of Israel during the exodus across the desert, and on the mouth of the Jews as they listen to Jesus making his 'bread of life' discourse in Chapter 6 of the Gospel of John.

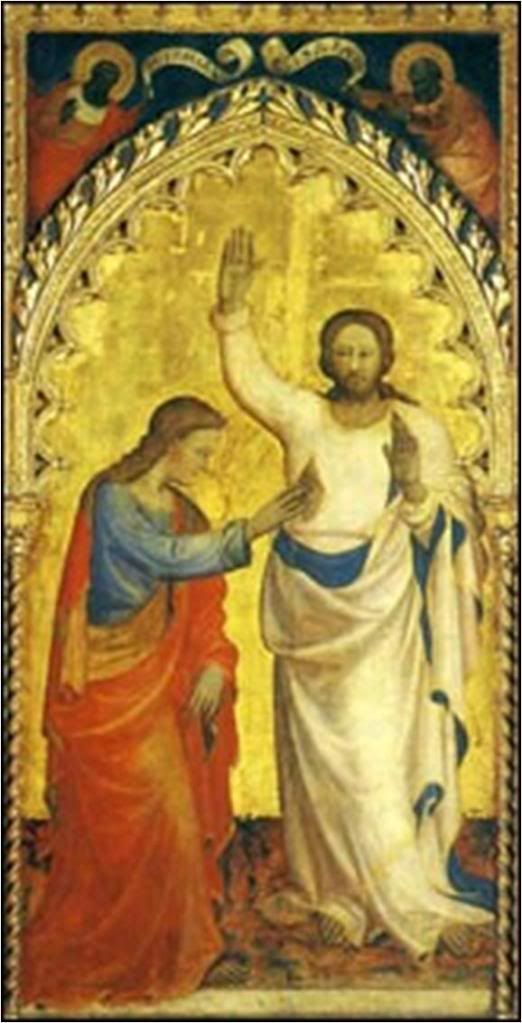

Giovanni Toscani, The Disbelief of Thomas, Accademia, Florence.

Giovanni Toscani, The Disbelief of Thomas, Accademia, Florence.

Disbelief touched the disciples who were 'scandalized' by and therefore rejected the way of the Cross, while considering the resurrection as something 'impossible'. ("Stop disbelieving", the Risen Lord tells Thomas.)

We can classify therewith the more consistent typology of present-day pseudo-atheism, what has been called religious indifference.

It is based on a superficial reading of history, a history from which God is absent - in which he is totally irrelevant, he generates no drama, he is not the guiding principle for moral choices, he is consigned to the limbo of ethereal fantasies. He is not fought against, but ignored because he is a disturbing 'fact' and therefore not relevant.

As the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor observed ironically, in an essay on the contemporary Secular Age, if God had to enter into contemporary society, at the very least, he would be asked to show his identification papers.

The second Biblical model is that of idolatry - this is much closer to the true 'dramatic' idea of atheism. It is not necessary to describe its characteristics because it comes up so often in Scriptures - on the one hand, the temptation to replace God with an object or with man himself; and on the other hand, the anti-idolatry criticisms and condemnations of the prophets, teh sages, and the witnesses to God.

In practice, it has meant a substitution of transcendence with some immanent historical data. St. Paul vehemently denounces this contradiction in Chapter 1 of the Letter to the Romans when he accuses the pagans of having replaced divine truth with a convenient system which ultimately generates libertinism and moral degradation.

In its 'noble' form, modern idolatry is the identification of constitutive and dynamic principles inherent in being, with history itself as their only explicative reasons.

We can cite the dialectical materialism of the Marxist kind, but also the so-called 'spirit' immanent in being itself, the motor of history, according to the Hegelian concept; or atheistic humanism, in which man is the measure and meaning of all being.

Adoration of the Dragon, Gothic tapestry, Angers Castle, France.

Adoration of the Dragon, Gothic tapestry, Angers Castle, France.

Therefore, idolatry is not simp0ly limited to the self-adoration of the self-sufficient man or the banal veneration of symbolic objects as in folk idolatry or in secular consumerism.

Idolatry also includes so many other sophisticated concepts that have been elaborated to exclude the possibility of divine transcendence.

The Bible offers a third example which is surprising because it may even be considered 'religious'. It is the provocative absence of God, his silence that leads to the capital question, "Where is God?", as many of the Psalms do: "My tears have been my food day and night, as they ask daily,'Where is your God?'" (42,4); "Why should the nations say, "Where is their God?" (79,10).

This seemingly 'atheistic' question can only arise from someonea person who has a crisis of faith, the authentic believer who is disconcerted by a 'mute and absent' God, especially in the face of the apparent triumph of evil.

The Bible is, in this regard, very illustrative. There is, in fact, a figure like Qohelet who incarnates the crisis of a man in the midst of an undecipherable world - one deprived of any perceptible meaning, defined by emptiness (

habel = vanity, smoke, emptiness), in which questions addressed towards a mute heaven simply fall back on he who questions.

William Blake, Job reproached by his friends, J. Puierpont Morgan Library.

William Blake, Job reproached by his friends, J. Puierpont Morgan Library.

But there is also the pure believer like Job, who insists on his desire to get an answer from the true God, seemingly taciturn and indifferent - not an apologetics formula prefabricated by theologians, tired defenders of official religion.

Rather, he exclaims: "I cry out to you and you do not answer!" And in the end, this absence of God proves to be fecund, it is transformed into a presence and an encounter: "I had heard of you by word of mouth, but now my eye has seen you" (42,5).

It is paradoxical, but even Jesus Christ, Son of God, having been truly human, went through this same experience of the Father's silence, on Gethsemane as well as on the Cross, thus revealing the mysterious positiveness of such absence.

Thus it is necessary, when considering the subject of atheism, to make a series of distinctions: between disbelief and agnostic indiffrence, between idolatry and systematic atheism, between the absence of God and the mystery of the divine 'incomprehensible'.

Through such distinctions one can see how complex are the pastoral problems to which they give rise. It is one thing, in fact, to engage in a locked confrontation of ideas with a consistent and conscious atheism, which is even capable of having its own ethics, as in the 19th century with Marxism and the idealistic rationalism of the Enlightenment.

From that encounter-confrontation, neither of the contenders came out unbloodied, but the results were invaluable for both sides. Just to give an example, during the 19th and 20th centuries, through its duel with Marxism, the Church matured its consciousness of the importance of the social question (thus,

Rerum novarum and the other social encyclicals that followed).

On the other hand, Marxism led to a post-Marxism in a philosopehr like Ernst Bloch, who affirted the extraordinary importance of Exodus as a founding text for freedom and liberation, and of Christianity as a transformative seed in history (one of his works had the emblematic title

Atheism in Christianity) which carries within the radical tension of the hope principle.

Quite another matter is indifference-disbelief which questions both authentic and working faith as well as extreme committed atheism. It is like a fog that is difficult to dispel; it neither has anxiety nor any 'questions'; it feeds on stereotypes and banality, content to live superficially, simply skimming fundamental problems, as the well-known image from the Diary of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard: "The ship is in the hands of the cook on board, and what the commandant's megaphone annnounces is no longer the route to follow, but what we shall eat tomorrow".

The modern means of mass communications teach us everything about fashions and lifestyles but ignore the meaning of existence, the anxiety of interior searching, questions about the beyond and about the Other with respect to ourselves and to the human horizon.

School of Raphael, Adoration of the Golden Calf, Vatican Loggias.

School of Raphael, Adoration of the Golden Calf, Vatican Loggias.

Finally, it is yet another matter to deal with the dark night of the soul when God is absent. One must feel the absence: the philosopher Martin Heidegger observed that "the true poverty of the world is when it no longer feels the absence of God as an absence".

He who is conscious of, and suffers from, interior emptiness, who yearns for the truth, for beauty and for love, not having them; he who obeys the injunctions of his own conscience although he perceives seemingly empty heavens (or at the most, crowded with the satellites of technology) - is one whom we might consider to have accepted the absolute Being of God despite affirming his own agnosticism ('I do not know if there is a God"). Remember the theologian Karl Rahner's famous thesis of the 'anonymous Christian'.

This experience of the absence of God is not just an experience of faith - which is often simultaneously light and shadows, certainty and doubt - but even of mysticism, as we see from the unforgettable pages of St. John of the Cross

[to whom we owe the expression 'dark night of the soul'] or the ardent reflections of Meister Eckhart or the incandescent verses of Angelo Silesio.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 17/08/2009 19:50]