Montreal's St. Andre:

Montreal's St. Andre:

A 'shining example'

Oct.. 17. 2010

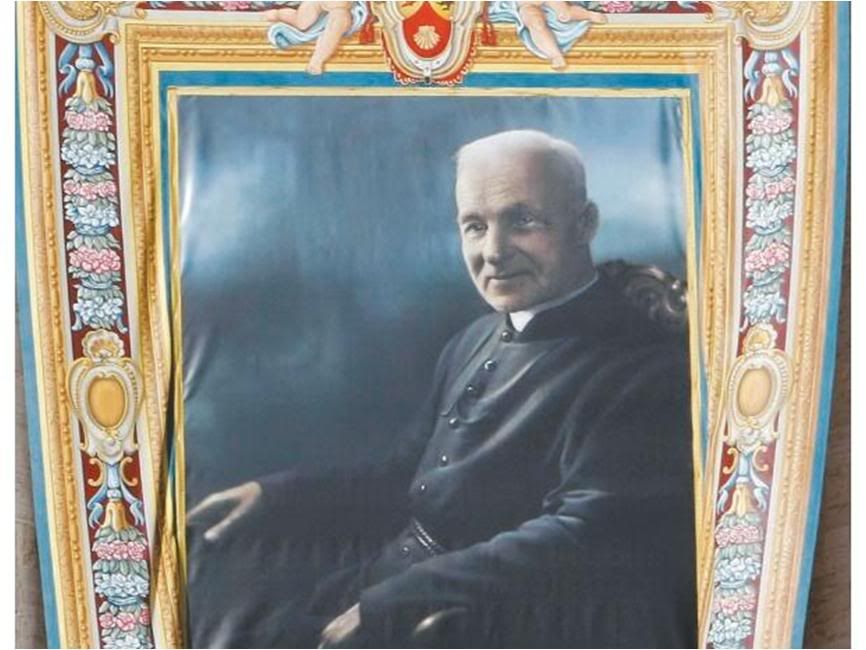

Below towering rooftop statues of Jesus Christ, John the Baptist and 11 apostles, Canada's latest saint smiled down from a tapestry flapping in a brisk wind on the facade of St. Peter's Basilica yesterday.

On an altar in St. Peter's Square, Pope Benedict XVI recognized the humble, diminutive lay brother as a saint, placing him in Catholicism's pantheon, the culmination of a process that Montreal Catholics have been shepherding since he died 73 years ago.

In top right photo, Canada's official delegation to the rites - Mayor Gerald Tremblay of Montreal, Senate Spaker Noel Kinsella and Foreign Minister Lawrence Canon.

In top right photo, Canada's official delegation to the rites - Mayor Gerald Tremblay of Montreal, Senate Spaker Noel Kinsella and Foreign Minister Lawrence Canon.

With an estimated 3,000 Quebec faithful watching in the square, and many Quebec and Canadian flags on display, Pope Benedict urged Canada's Catholics to follow the "shining example" of St. Andre Bessette, the man better known to Montrealers as Frere Andre (Brother Andre).

Friend to the poor and sick, founder of Montreal's St. Joseph's Oratory, and dubbed the Miracle Man of Montreal, Brother Andre officially joined the sainthood along with five others during an elaborate ceremony in the square, marked by joyous singing by several choirs.

Despite dire forecasts the previous day, rain never materialized and the cloud cover cleared occasionally to warm the masses.

In a homily before an estimated 80,000 pilgrims from around the world, Pope Benedict said St. Andre Bessette "knew suffering and poverty very early in life."

Born to an extremely poor family in St. Gregoire, southeast of Montreal, Bessette was orphaned at age 12 and drifted for years as an illiterate, unskilled worker.

In 1870, he joined the Congregation of Holy Cross, a group which reluctantly accepted him and assigned him a lowly job in the reception area of College Notre-Dame in Montreal. His early-life difficulties "led him to turn to God for prayer and an intense interior life," Pope Benedict said.

"Doorman at College Notre-Dame in Montreal, he showed boundless charity and did everything possible to soothe the despair of those who confided in him."

Bessette "was the witness of many healings and conversions. 'Do not try to have your trials taken away from you,' he said, 'rather, ask for the grace to endure them,'" Pope Benedict added.

"For him, everything spoke of God and His presence. May the example of Brother Andre inspire Canadian Christian life."

Pope Benedict was accompanied by five cardinals, 10 archbishops, 13 bishops and 20 priests. Among them was Jean-Claude Turcotte, Archbishop of Montreal. Along with Quebecers, about 2,000 other pilgrims were in Rome to celebrate Brother Andre's canonization, from places such as the United States and India.

Those in the crowd in Rome to support Brother Andre were easy to spot: They wore white scarves around their necks bearing images of the new saint and St. Joseph's Oratory, along with the words: "A friend, a brother, a saint."

I was wondering whether Canada had been struck with the same 'Marymania' that appears to have had secular Australia in a spell over the past few weeks - and this earlier commentary in the National Post confirms a similar phenomenon in ueber-secular Canada, at least in Quebec province.

Brother André canonization reconnects

Montreal with its Catholic past

By Graeme Hamilton

Left, a wax model of Brother André in the museum at St. Joseph's Oratory in Montreal; right, in a stained-glass window in the University of Toronto.

Left, a wax model of Brother André in the museum at St. Joseph's Oratory in Montreal; right, in a stained-glass window in the University of Toronto.

Reading the newspapers, watching television news, even riding the metro in Montreal these days, one would never guess that Quebec has broken with its Catholic past.

Black-and-white images of Brother André, who will be canonized by Pope Benedict XVI in Rome Sunday, are everywhere. There are ads celebrating him in the subway system, the two French-language news networks will begin live coverage from Rome early in the morning and the

Journal de Montréal was promising a 16-page special section Saturday about the soon-to-be saint, who died in 1937.

In two weeks, a Mass celebrating his sainthood is expected to draw more than 50,000 people to the Olympic Stadium. It is the kind of treatment usually reserved for a pop star like Celine Dion or hockey’s Montreal Canadiens.

“There’s going to be a bit of that Québécois pride. It’s Brother André. He’s one of us,” said Spencer Boudreau, a McGill University professor of religious education. “Even if the majority of them aren’t going to church, it’s Frère André.”

The desertion of Quebec churches after the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s is well documented. Once a central player in family life, education and social services, the Catholic Church surrendered those roles to the provincial government.

Regular church attendance, once estimated at close to 90%, has plummeted to less than 15%.

But that has not stopped Quebecers from calling themselves Catholics. University of Lethbridge sociologist Reginald Bibby calls it “the Quebec anomaly.”

In a 2007 paper, he noted that despite the steep drop-off in church attendance, the proportion of Quebecers identifying themselves as Catholic was 83% in the 2001 census, down only slightly from 88% 40 years earlier.

There remains a strong attachment to symbols of the province’s Catholic heritage. When a commission studying the accommodation of religious minorities suggested it would be a good idea for a secular state like Quebec to remove the crucifix hanging in the provincial legislature, the proposal was immediately shot down.

“Try to touch the cross on the mountain or change Sainte Catherine Street to Catherine Street and there’d be an outcry,” Mr. Boudreau said. “That’s part of our identity.”

Rather than being rejected as a relic from Quebec’s priest-ridden past, Brother André is being redrawn as a folk hero who symbolizes the triumph of a little guy born into poverty and poor health.

“There is a lot of emphasis on his poverty, on the fact that he had little education,” said Raymond Lemieux, professor emeritus in the faculty of theology at Université Laval. “That touches a portion of the population that is generally left aside.”

The slogan on the advertisements taken out by St. Joseph’s Oratory, the towering Montreal shrine that Brother André helped build, describe him as “a friend, a brother, a saint.” That resonates even with people who do not attend church, said Danielle Decelles, a spokeswoman for the Oratory.

“Brother André can be, as our slogan says, a friend, a brother,” she said. “He lived like us. He was from here and he lived an ordinary life like everyone lived at the time. He was someone close to the people, and he is still seen that way.” He was a humble man who “reached the highest step,” the advertisement says.

Robert Mager, a professor of theology at Université Laval, said Brother André represents

a popular Catholicism that has endured while institutional religion withers.

[Very apropos to Benedict XVI's reminder to seminarians to respect popular piety, allowing for some degree of irrationality.]

“There are still many Quebecers who go to shrines or who go to monasteries to spend a weekend, even if they don’t go to church,” he said. “These are people who are attached to a very emotional sort of religion, related to spirituality, and they find that pilgrimages suit them.”

Brother André, who attracted an estimated one million mourners when he died at age 91, was credited with healing powers. Pilgrims by the thousand continue to visit the Oratory in hopes of finding a cure.

“Brother André was at the heart of the interface between the sacred and death and illness,” Mr. Mager said. “Many people who are personally suffering from illness, the death of a loved one or difficulties in life like the break-up of a couple, will go towards someone like Brother André, who represents what religion can offer as hope.”

Mr. Boudreau said he tells his students at McGill to think of saints as role models. “From the Catholic perspective, these are models of holiness and that simple people can attain great heights,” he said. “It’s counter-cultural in a sense. Somebody who has taken a vow of poverty, chastity and obedience and devotes his life to the sick is really not what the world of consumerism is all about.”

The Church is clearly hoping the excitement generated by Brother André’s canonization will spark some renewed interest in Catholicism in Quebec. But Mr. Boudreau said he doubts the effect will be long lasting. In order to be declared a saint, the Vatican must confirm two posthumous miracles.

“That would be the third miracle of Brother André if church attendance went up,” Mr. Boudreau joked.

Why is there fascination for the new Catholic saints even in hyper-secularized societies like Australia and Canada? As the article above partly indicates, it's because the Catholic Church is the only religion that elevates ordinary mortals, including beggars, shepherds and doormen, to an honor like sainthood.

Indian divinities have their roots in the mists of long-ancient myths, and various Hindu sects have their iconic holy men but usually only one at a time, as are continuing reincarnations of the ancient gods; Tibetan Buddhists have continuously reincarnated lamas. Their common characteristic is that they are seen as supernatural beings.

So perhaps the universal appeal of Catholic saints is that even in ordinary and humble callings, they show that regular folk can be shining examples of a selfless holy life for other regular folk to emulate. And that in the past, as in the present, there does not seem to be a shortage of such selfless holy persons. Not all of them may eventually be known by name but we know they exist as part of the vast legion of the communion of saints.....

I had to look up the reference in the title of the next article, which is a more fleshed-out acocunt of St. Andre's life. Rocket Richard was the popular nickname to Canada's most prolific goalmaker in the history of Canadian ice hocket. He played from 1942 to 1960 for the Montreal home team.

Brother André:

The Rocket Richard of miracles

by Eric Reguly

Oct. 15, 2010

A young boy from Quebec lay in hospital, near death. A road accident victim, he had suffered massive cranial trauma and was evidently in an irreversible coma. Any doctor will tell you that recovery from serious head injuries is exceedingly rare.

The boy’s family and friends prayed to Brother André, the founder of Montreal’s Oratoire Saint-Joseph du Mont-Royal and a man famous for healings; he had been beatified in 1982, four decades after his death.

Against all odds, the boy emerged from his coma. The recovery was judged scientifically inexplicable by several doctors.

The Vatican confirmed a second miracle attributed to André late last year; two are necessary, one for the beatification, the other for the

posthumous canonization[All beatifications and canonizations are posthumous!], which will be formalized in St. Peter’s Square in Rome by Pope Benedict XVI on Sunday.

And the boy? He has returned to health after the 1999 accident, when he was 9 years old, and will be among 5,000 Canadians making the pilgrimage to Rome to watch André’s elevation to sainthood. His identity has never been revealed.

“He’ll certainly be among the crowd at St. Peter’s,” said Mario Lachapelle, the Quebec priest who, as a member of the Congregation of Holy Cross, was André’s vice-postulator, a middleman who sponsors and pleads the canonizations to the Vatican. “But he and his family are humble people and they value their privacy.”

If the boy – now young man – does reveal his identity, he will become an instant international celebrity, for André’s healings are known throughout the Catholic world, from Canada to the Philippines.

In Italy, Father Lachapelle said André is known as the “Padro Pio” of Canada, a reference to the famous southern Italian priest, known for his stigmata and healings, who was canonized in 2002.

André’s canonization on what should be a warm, sunny autumn day in Rome will be one of the biggest spectacles of Pope Benedict’s reign. Canonizations are still relatively rare, even though Benedict’s predecessor, Pope John Paul II, cranked up the Vatican’s saint-making machine with alacrity, to the point he was accused by one Italian observer of churchly matters of using saints as “Vatican marketing decisions.”

André will be one of six canonizations, and will be the first Canadian male saint born on Canadian soil. Marie-Marguerite d’Youville, founder of Montreal’s Order of Sisters of Charity, was the first Canadian-born saint and was canonized in 1990.

The event starts at 10 a.m. and promises to be a festival of colour and ceremony, with tens of thousands of visitors, many of them politicians, ambassadors and senior Roman Catholic Church officials from the countries that claim the fresh saints.

While Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Quebec Premier Jean Charest are not expected to attend, Minister of Foreign Affairs Lawrence Cannon and Gerald Tremblay, the mayor of Montreal, among others, will be in the throng.

The Canadian church will send five bishops, four archbishops and two cardinals, Marc Ouellet and Jean-Claude Turcotte, plus an army of nuns and priests..

André is a superstar in his native province. When he died at age 91 of old age – there is no medical record of a fatal disease – on Jan. 6, 1937, a million people filed by his coffin, the equivalent to one in three Quebec residents at the time.

“For Montreal, his canonization is a great drawing card,” said Anne Leahy, Canada’s ambassador to the Holy See in Rome. “People in Quebec are proud of Frère André just like they are proud of Maurice Richard.”

André’s body, placed in the Crypt Church, below the present day basilica, was a sight to behold. Piled against the walls were hundreds of crutches that had been owned by cripples allegedly cured by André. He is associated with an extraordinary 125,000 miracles, though he never considered himself a healer. Instead, he urged the unwell to see a doctor or pray.

The Vatican has been exploiting miracles forever. It first cranked up the saint conveyor belt in the centuries after the death of Jesus Christ, when Christians were persecuted by the Romans. Back then, virtually any martyr became a saint.

[And it remains so, Mr. Ignorant Reporter. Because martyrdom is the ultimate sacrifice for the faith, an imitation of Christ that merits instant recognition if the victim was killed 'in odium fidei', out of hatred for the faith.]

In later centuries, the definition of saint was broadened to include

the ultra-faithful and pious.

[Not being Catholic, the reporter just does not get the concept of holiness that underlies all the causes for sainthood!]

The number of saints, of course multiplied. The saint glut troubled the 12th Century pope, Alexander III, who imposed tighter restrictions on canonizations.

The modern-day criteria for sainthood date back to the 17th Century, when it took four posthumous miracles (recently reduced to two) to qualify. The Vatican insists on the use of independent doctors to verify that healings – the vast majority of miracles are medical cures – are scientifically unexplainable.

Under Pope John Paul II, the canonization process was simplified by the elimination of the Devil’s Advocate, the Vatican official who would argue against sainthood. Saintly inflation rates exploded to almost 500 canonizations, including Mother Teresa’s.

[Reguly does not take into account that the number included mass sainthood for martyrs in Asia and Africa and the Spanish Civil War, who numbered in the dozens!]

André’s first Vatican-confirmed miracle was the healing in 1958 of a Quebec man, Giuseppe Carlo Audino, who suffered from cancer. He prayed to André and the cancer disappeared. This miracle was cited in André’s beatification by John Paul II in 1982.

Father Lachappelle, who has spent his career studying André, said some of the stories of miracles were fantastic. “He would say [to a cripple], ‘You’re not sick, so leave you’re crutches here.’ And some of them just walked away,” he said.

André saw himself as a simple man, incapable of miracles “I am nothing,” he would say, “only a tool in the hands of Providence, a lowly instrument at the service of St. Joseph.”

Father Lachappelle said what interests him most about André’s life is not so much the healings but his unconditional acceptances of others and his ability to speak simply about the love of God. And what he calls his “avant-garde” ecumenism.

“What is fascinating about Brother André is that he was so much ahead of his time,” he said. “He was a father figure, and did not have an image of God as a dispenser of justice.”

André, he said, was “avant-garde” in the sense that he was unusually liberal for his time. For example, he befriended non-Catholics and non-Christians, a rarity for devout men of the Church in that era.

One of his closest friends was George H. Ham, the Protestant newspaperman who published the first biography of André, “The Miracle Man of Montreal,” in 1921.

André was born Alfred Bessette, one of ten children, in a town about 40 kilometres southeast of Montreal in 1845. He had a miserable upbringing. He was only nine when his father was killed by a falling tree. Three years later his mother died of tuberculosis.

André was small and sickly, had little schooling and was largely illiterate. He never wrote a full sentence in his life, making the research into his career, his spirituality and his miracles reliant on the observations of friends, fellow brothers, eyewitnesses and biographers.

After his parents died, he bounced from family to family, job to job and worked as a farm hand, tinsmith, blacksmith, baker, shoemaker, coachman and, four years, in textiles mills in the United States. He returned in 1867, the year of Canadian confederation, and presented himself in 1870 to the Congregation of Holy Cross in Montreal, where he was given the name Brother André and a low-exertion job as porter at Notre-Dame College.

He doubled up as a floor washer and barber, and the sacks of coins he saved over the years from his five-cent-a-pop haircuts would later be used to finance the building of a chapel on Montreal’s Mont Royal. The chapel, which still exists, is next to the larger Crypt Church that was completed under André’s watch in 1917.

The basilica, which was started in 1924 and not completed until 30 years after André’s death, sits atop the Crypt Church. Dedicated to St. Joseph and inspired by André, the basilica’s 97-metre-high dome is the world’s third largest of its kind.

André would become better known as a healer than a builder. He had an affinity for the poor and the ill and visited them everywhere. He would urge them to pray to St. Joseph or rub a medal of the saint.

In time he gained the reputation as someone who could cure sickness – a miracle worker – and the people would go to him in the hundreds, then thousands. Some allegedly were cured, others died, though his friends said anyone who met him felt enriched or transformed in some way.

On Sunday, the Vatican will officially recognize André as the miracle worker he insisted he wasn’t. Quebec will celebrate, along with the young man in St. Peter’s Square whose family is convinced André saved their son’s life.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 19/10/2010 02:46]