| | | OFFLINE | | Post: 19.092

Post: 1.738 | Registrato il: 28/08/2005

Registrato il: 20/01/2009 | Administratore | Utente Veteran | |

|

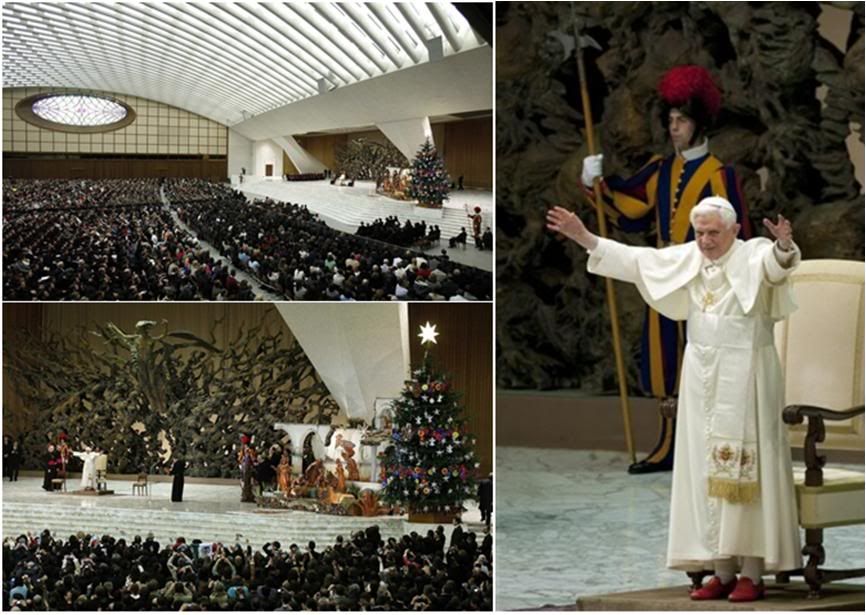

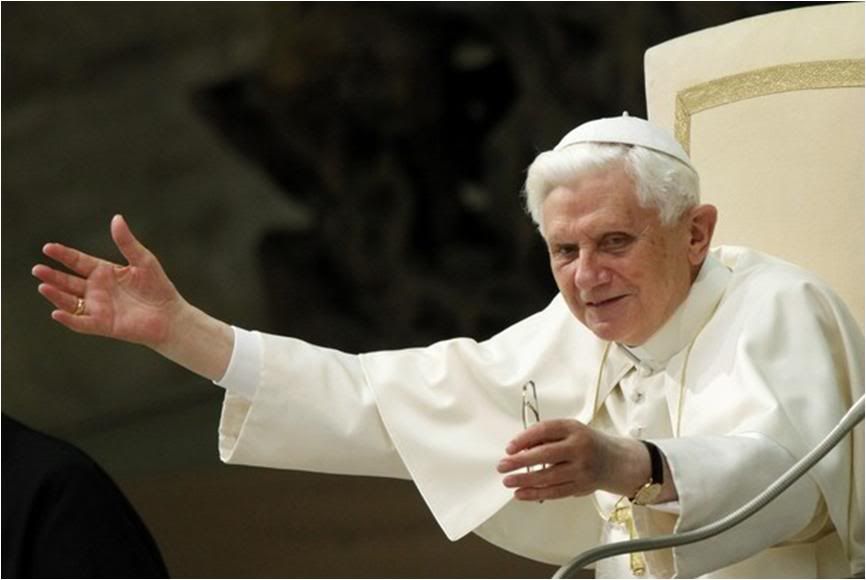

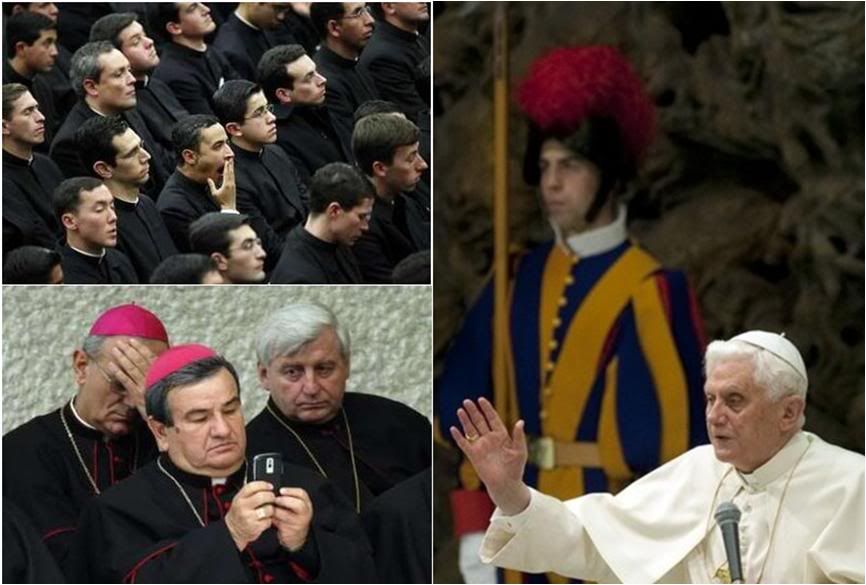

GENERAL AUDIENCE TODAY

GENERAL AUDIENCE TODAY

Continuing his catechetical cycle on the great Christian writers of the Middle Ages, the Holy Father spoke today on John of Salisbury, a 12th century English monk,

Here is how the Holy Father synthesized the lesson in English:

In our catechesis on the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, we now turn to John of Salisbury, an outstanding philosopher and theologian of the twelfth century.

Born in England, John was educated in Paris and Chartres. A close associate of Saint Thomas Becket, he was involved in the crisis between the Church and the Crown under King Henry II, and died as Bishop of Chartres.

In his celebrated work, the Metalogicon, John teaches that authentic philosophy is by nature communicative: it bears fruit in a message of wisdom which serves the building up of society in truth and goodness.

While acknowledging the limitations of human reason, John insists that it can attain to the truth through dialogue and argumentation. Faith, which grants a share in God’s perfect knowledge, helps reason to realize its full potential.

In another work, the Policraticus, John defends reason’s capacity to know the objective truth underlying the universal natural law, and its obligation to embody that law in all positive legislation.

John’s insights are most timely today, in light of the threats to human life and dignity posed by legislation inspired more by the "dictatorship of relativism" than by the sober use of right reason and concern for the principles of truth and justice inscribed in the natural law.

Here is a full translation of the Pope's catechesis:

Dear brothers and sisters,

Today we will come to know the figure of John of Salisbury who belonged to one of the most important philosophical and theological schools of the twelfth century - that of the Cathedral of Chartres, in France.

Like the theologians I have spoken of in the past weeks, he too helps us to understand how faith, in harmony with the just aspirations of reason, can propel the mind towards revealed truth in which man finds his true good.

John was born in Salisbury, England, some time between 100 and 1120. Reading his works, especially his rich epistolary, we are able to learn some of the most important facts of his life.

For almost 12 years, from 1136 to 1148, he dedicated himself to study, attending the most qualified schools of the day, listening to famous teachers. He went to Paris and then to Chartres, the environment that marked his formation the most, and from which he assimilated his great cultural openness, his interest for speculative problems and his appreciation of literature.

As it often happened in those days, the most brilliant students were asked by prelates and sovereigns to become their close collaborators. This was the case with John of Salisbury, who was presented by his great friend, Bernard of Clairvaux, to Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury - the primate See of England - who gladly welcomed John to his clergy.

For eleven years, from 1150 to 1161, John was secretary and chaplain to the aging Theobald. With indefatigable zeal, even as he continued to devote himself to study, he also carried out intense diplomatic activity, going to Italy ten times for the specific purpose of tending to the relations of the Kingdom and the Church in England with the Roman Pontiff.

In those years, the Pope was Adrian IV, an Englishman who had a close friendship with John. In the years following Adrian IV's death in 1159, great tension arose in England between the Kingdom and the Church.

In fact, Henry II intended to affirm his authority over the internal life of the Church, limiting its freedom. This roused reaction from John of Salisbury, and especially, the courageous resistance of Theobald's successor as Archbishop, St. Thomas Becket, who was exiled to France for this reason.

John of Salisbury accompanied him to exile and remained in his service, while always working for a reconciliation [with the King].

In 1170 when both Becket and John had returned to England, Becket was assaulted and murdered in his own cathedral. He died a martyr and was always venerated as such by his people.

John continued to serve Becket's successor faithfully, until he was elected Bishop of Chartres, where he served from 1176 to his death in 1180.

Of the works of John of Salisbury, I wish to single out the two which are considered his masterpieces, with elegant Greek titles - Metaloghicón (In defense of logic) and Polycráticus (The man of government).

in the first book, not without the subtle irony that characterizes many men of culture, he rejected the position of those who had a reductive idea of culture, which they considered as empty eloquence, useless words.

John eulogizes culture as authentic philosophy - that is, the encounter between forceful thought and communication, effective words.

He wrote: "Indeed, just as the unenlightened eloquence of reason is not only fearsome but also blind, so wisdom that does not avail of the use of words is not just weak but in a certain way, lame. Indeed, even if wisdom without words can serve one's own conscience, it is rarely of use to society" (Metaloghicón 1,1, PL 199,327).

A very relevant teaching today. What John called 'eloquence' - the possiblity of communicating with instruments that are ever more developed and widespread - has multiplied enormously today.

Nonetheless, all the more urgent is the need to communicate messages endowed with 'knowledge', inspired by the truth, by goodness, by beauty.

This is a great responsibility, which particularly concerns persons who work in the multiform and complex field of culture, communications, the media. And it is a field in which the Gospel can be announced with missionary vigor.

In the Metaloghicón, John confronts the problems of logic, which were of great interest in his time, and asks a fundamental question: what exactly can human reason know? Up to what point can it correspond to the aspiration in every man to search for the truth?

John of Salisbury takes a moderate position, based on the teachings in some treatises of Aristotle and of Cicero. According to him, human reason generally arrives at knowledge that is not indisputable but probable and opinable.

He concludes that human reason is imperfect because it is subject to finiteness, to the limits of man. However, it grows and improves itself through experience and the elaboration of correct and coherent reasoning that is capable of establishing a relationship between concept and reality, by discussion, confrontation, and the enrichment of knowledge from generation to generation.

Only God has perfect knowledge which he communicates to man, at least partially, through Revelation that is received in faith, and for which the science of the faith - theology - displays the potential of reason and humbly causes it to advance in the knowledge of the mysteries of God.

The believer and the theologian, who explore the depths of the treasury of faith, also open themselves to practical knowledge which guides daily activity, and therefore, to moral laws and the exercise of virtue.

John of Salisbury writes: "God's clemency has granted us his law, that establishes which things are useful for us to know, and tells us what is licit to be known of God and how much we may correctly investigate about him.... Indeed, this law makes the will of God explicit and clear, in order that each of us may know what we need to do" (Metaloghicón 4,41, PL 199,944-945).

But John says there also exists an objective immutable truth, which originates in God, which is accessible to human reason and concerns man's practical and social actions. This is a human right, he says, which should inspire human laws as well as political and religious authorities so that they can promote the common good.

This natural law is characterized by a property that John calls 'equity', namely, the attribution of rights to every person. This gives rise to precepts that are legitimate for all peoples and that cannot be abrogated in any case.

That is the central thesis of the Polycraticus, John's treatise on political philosophy and theology, in which he reflects on the conditions that make the actions of those who govern just and permissible.

While other arguments in these books are linked to the historical circumstances within which they were written, the subject of the relationship between natural law and a positive juridical order mediated by equity is still of great importance today.

in our time, in fact, and especially in some countries, we are witnessing a preoccupying separation between reason - which has the task of discovering the ethical values linked to human dignity, and freedom - which has the responsibility to accept and promote these values.

Perhaps John of Salisbury would remind us today that only those laws correspond to equity which protect the sacredness of human life and reject the licitness of abortion, euthanasia and dispassionate genetic experimentation, laws that respect the dignity of matrimony between a man and a woman, that inspire a correct secularity in the State - a secularity that would always include the protection of religious freedom - and which pursues subsidiarity and solidarity at the national and international levels.

Otherwise, what ends up being installed is what John of Salisbury calls 'the tyranny of princes' - as we say today, 'the dictatorship of relativism', a relativism which, as I pointed out a few years ago, "does not recognize anything as definitive and whose ultimate goal consists solely of one's own ego and desires" (Missa pro eligendo Romano Pontifice, Homily, April 18, 2005).

In my recent encyclical, Caritas in veritate, addressing all men of goodwill to commit themselves so that social and political action may never be detached from the objective truth about man and his dignity, I wrote:

"Truth, and the love which it reveals, cannot be produced: they can only be received as a gift. Their ultimate source is not, and cannot be, mankind, but only God, who is himself Truth and Love. This principle is extremely important for society and for development, since neither can be a purely human product; the vocation to development on the part of individuals and peoples is not based simply on human choice, but is an intrinsic part of a plan that is prior to us and constitutes for all of us a duty to be freely accepted" (No. 52).

This plan which came before us, this truth of being, is what we must seek and accept in order that justice may be born, but we can find it and accept it only with a heart, a will, and reason purified in the light of God.

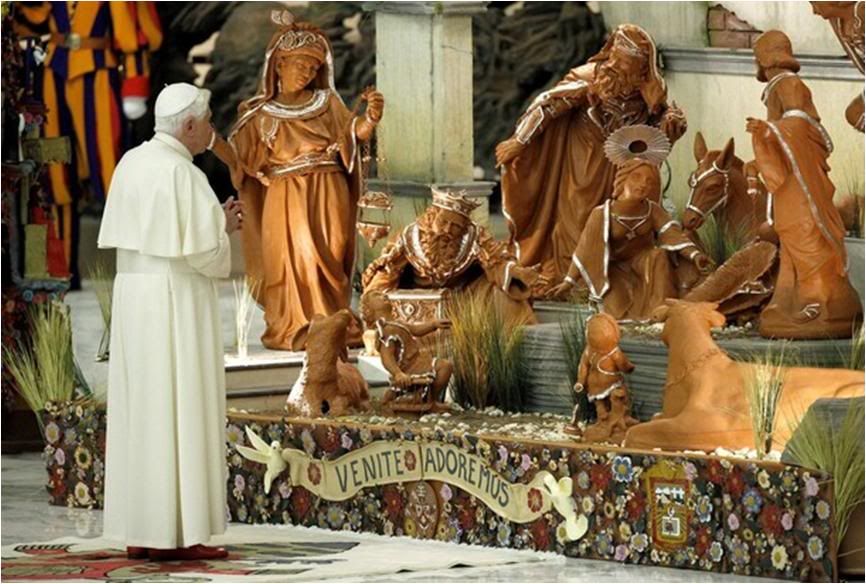

Two special events after today's audience were the formal presentation to the Holy Father by a delegation from Mexico of the creche for the Aula Paolo VI this year; and the Holy Father was formally made an honorary citizen of Introd, the commune in Val d'Aosta that has jurisdiction of the papal summer residence at Les Combes. where Benedict XVI has spent three of his five summer vacations as Pope.

The statues were fashioned from limestone by Mexican artisans, with the angel figures in tin.

The statues were fashioned from limestone by Mexican artisans, with the angel figures in tin.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 16/12/2009 19:59] |