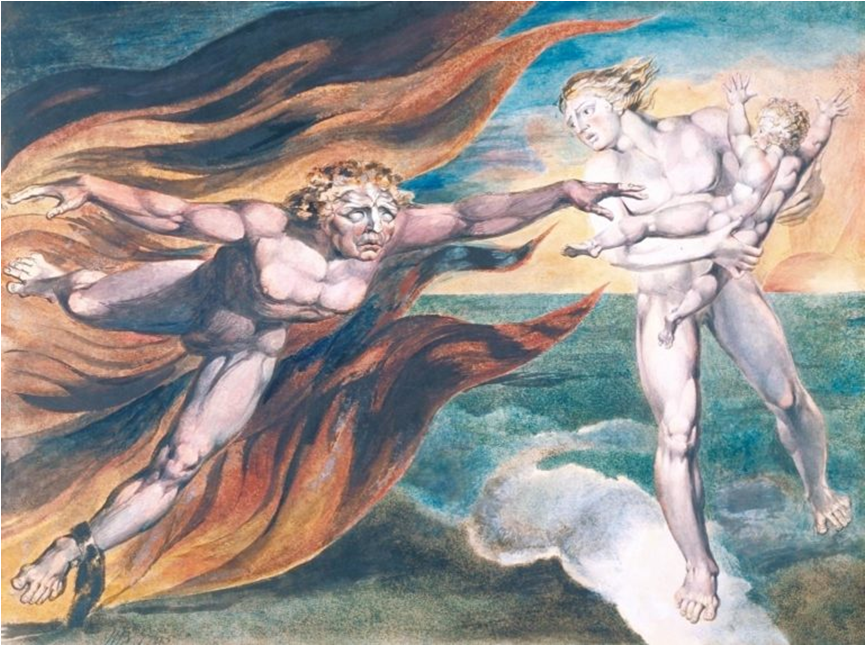

The Good and Evil Angels, William Blake, c. 1800 (Tate Gallery, London)

Private judgment and anarchy

The Good and Evil Angels, William Blake, c. 1800 (Tate Gallery, London)

Private judgment and anarchy

Why Catholic teaching and the structure of the Church

kept European society together - and Protestantism

has fostered anarchy in 'freedom of thought'

by David Carlin

APRIL 21, 2017

It was Auguste Comte (1798-1857) who said,

“Ideas govern the world.” [Tell that to Jorge Bergoglio!]

By “ideas,” he meant beliefs and values; not so much the beliefs and values of individuals as the beliefs and values of a society. If a society is to hold together – if it is to cohere – its members must generally agree on a system of ideas. If there is considerable disagreement on beliefs and values, the society in question will tend to fall apart.

Though he didn’t believe in God or life after death, Comte was a great admirer of the Catholic Church. Its time, for him, had come and gone, but in the Middle Ages it had been just right; it was European society’s indispensable institution. For it provided the system of commonly held ideas needed to hold European society together: the system called Christian theology (or mythology as some by his day preferred).

Further, the Church had a marvelous structure, centered in the pope, while at the same time decentralized in bishops and still further decentralized in parish priests. So greatly did Comte admire the Church of Rome that he would have been happy to see it govern the modern world – if only it would be so modern as to abandon its belief in God and accept instead the teachings of Comte.

The marvelous unity of the Middle Ages began to collapse with the coming of Protestantism and ]u]its disastrous principle (as Comte saw it) of private judgment. Protestants, having rejected the religious authority of the pope and his bishops, and having declared the Bible to be the one and only religious authority, had to exercise their own individual private judgment when reading the Bible.

At least that was the theory.

But early Protestant political leaders (e.g., Queen Elizabeth I in England, the Puritans in Massachusetts), sensing the anarchic tendencies of the principle of private judgment, did not hesitate to persecute those who ventured to exercise their private judgment in the “wrong” way.

In the long run, however, the private judgment principle belonged too much to the very essence of Protestantism to be suppressed. It survived, it flourished, it expanded. Modern people learned – first in the Protestant countries but then everywhere – that they had a right to “think for themselves.”

Freedom of thought became a fundamental principle of modernity; and not just freedom of thought when reading the Bible, but freedom of thought in all things: religion, morality, politics, art, literature, and anything else you can name.

Comte was no fan of freedom of thought; in fact, he was its great enemy. For he felt that it would lead to the breakdown of society, to intellectual and moral and political anarchy. We need, he held, a new authority to replace the old authority of the Catholic Church;

a new modern authority that can teach everybody to think the same way about the really important questions, the “big” questions – just as the Catholic Church used to teach everybody to think the same way about the big questions.

Where can we find that authority? In science and the scientists, Comte answered. Mathematicians, astronomers, physicists, chemists, and biologists can tell ordinary people what to believe about the world of nature, and ordinary people will be persuaded by those teachings because they are truly scientific.

But we will have to develop two new sciences, sociology (which will give us correct beliefs about history, politics, and society) and ethics (which will give us correct beliefs about right and wrong conduct). Comte himself kindly undertook to create these two final but very necessary sciences.

A new religion, the non-theistic Religion of Humanity, would be created, and the “priests” of this new religion would teach these seven sciences to the world, and the world would live in peace because everybody would agree on the most important beliefs and values, just as they did in the Catholic middle ages. Comte himself would be the high priest (in effect the pope) of this new religion, which would be headquartered not in Rome but in Paris.

Unfortunately for the unity of society, while the first five sciences (mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology) were, and still are, universally accepted, the final two (sociology and ethics) never became truly scientific.

In those two fields, private judgment continues to prevail today, more than 150 years after Comte made his noble but futile attempt to turn them into sciences. The Religion of Humanity never came about. Moral and intellectual anarchy continue to flourish.

When I consider a few of the crazier ideas that prevail widely today – for example, the idea that unborn babies are not babies, the idea that persons of the same sex can “marry” one another, and the idea (perhaps the craziest idea of all to date) that you can be of one sex, biologically given, and of an opposite gender, personally chosen – I remember Comte and his warnings about the dangers of private judgment.

Where will all this lead eventually? In two directions, I believe.

- First, since the anarchic dangers of free thought are so great, politically powerful forces will attempt to stifle free though not by persuasion (Comte’s way) but by compulsion and persecution (the way of Elizabethan England and Puritan Massachusetts).

- Second, since free thought is of the very essence of modernity, these attempts at compulsion and persecution will in the long run fail, and our moral and intellectual anarchy will grow worse and worse.

And where that will lead us, lacking some renaissance of religion or the moral sense, is difficult to say. But one thing is certain: it won’t be a pretty or very pleasant world.

A companion piece from Fr. Schall, which of course, does very well as a stand-alone.

On absolutes

by James V. Schall, S.J.

APRIL 25, 2017

The past participle of the Latin verb

absolvere is

absolutus. It means freed from any restrictions. Modern man wants no “absolutes.” He wants to be loosed from things binding for all times and places.

An “absolute” refers to lines not to be crossed. “Moral” absolutes can, in fact, be crossed. “Thou shalt not kill” does not mean that no killings will take place. It means that, on crossing, “absolute” consequences – either in the here or hereafter – follow.

All things not forgiven remain with us. Indeed, they remain with us even if they are forgiven. Our deeds and words form the character into which we have made ourselves. We are always a “this someone” who, in the days of our mortality, did or did not do this or that.

Let us suppose that we want to deny the existence of absolutes, how would we go about it? Initially, it is easy to imagine why we might want to rid the world of absolutes. Their elimination would, presumably, free us to do whatever we wanted to do with no fear of untoward repercussions.

No doubt, if I want to eliminate the prohibition against murder or stealing, I want it removed only for my own case. I do not want it universalized. I do not want others to feel perfectly free to wipe me out or, with impunity, to abscond unscathed with my hard-earned goods.

We cannot have it both ways. So viewed from this angle,

we really do not want absolutes abolished except as convenient for ourselves.

But if we still insist on abolishing absolutes, we might approach the issue from the angle of authority. Who says that any absolutes exist? Scripture, for instance, has some pretty hefty “thou shalt nots.” But why should we bother about Scripture? Who knows what it said? Who was around to check the accuracy of its recorded prohibitions? Why could not the “thou shalt nots” have held only in that ancient time or in those strange customs?

Descartes even worried that maybe the devil was deceiving us so that we could not rely on our senses to tell us anything reliable about what is going on in the world. But if no God exists – or, if we cannot figure out who said what – it is senseless to trust any authority that sets down absolutes. When Christ pardoned the lady caught in adultery, He told her: “Go and sin no more.” Wasn’t He violating her “rights” to live the way she wanted to live?

Still, if we find no divine authority capable of defining or enforcing absolutes, what about the state? Can’t it enforce whatever it wants? Isn’t that what Hobbes taught? This civil absolute power seems to be pretty much true. But states differ. They can change from day to day as to what they consider absolute. Opposites can be absolutes on given days.

Likewise, scientifically inter-related absolutes seem to exist. If they did not hold, the world would not stay together. No one wants to change the speed of light or the fact that we human beings are born with hands and brains. The range of sound waves that we can and cannot hear seems pretty absolute.

When we come right down to it, the number of absolutes that we might want to change is very minimal. The only way an outfielder can catch a fly ball is if a) the ball is not made of lead, b) a batter hits the fly, c) the ball comes down on an arc, and d) the legs, eyes, and hand of the fielder are so coordinated that they are there where the ball comes down. If these absolutes are not permanent, don’t bother to take me out to the ballgame.

If the world were not full of absolutes, we could not live in it. Indeed, we would not want to live in it. The problem that we human beings have concerns only a few absolutes. These are the absolutes that indicate what we are and how we ought to live, even when we do not observe them.

The annoying trouble with absolutes usually shows up when we do not observe them. For some reason, all sorts of unwelcome things happen to ourselves or others that we are reluctant to attribute to ignoring the absolutes. We develop a whole rhetoric that usually ends up reassuring us that what we did was just fine. The fact is that

no one can violate any absolute without giving some reason why it is quite all right.

Where does this leave us? We usually end up proving the existence of absolutes by seeing that our reasons to prove them wrong actually prove them right. The witticism that no good deed goes unpunished deserves one addendum: “No bad deed,” as Plato said, “goes unpunished either.” That too is an absolute.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 25/04/2017 14:13]