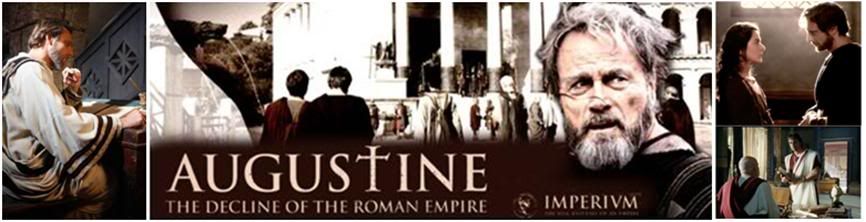

St. Augustine is very much on the mind of Italians this Sunday and Monday with the broadcast of the TV film 'Augustine'in two parts, which was previewed by Benedict XVI in abridged form last September.

St. Augustine is very much on the mind of Italians this Sunday and Monday with the broadcast of the TV film 'Augustine'in two parts, which was previewed by Benedict XVI in abridged form last September.

The film, a co-production by an Italian company with Bavarian TV, was born from a suggestion made by the Holy Father before his visit to Bavaria in 2006.

Speaking to German media representatives, he had remarked: "Make a film on Augustine, for example, to show that film subjects need not be about terrible situations. There are marvelous figures in history who are far from boring and whose lives are still very relevant."

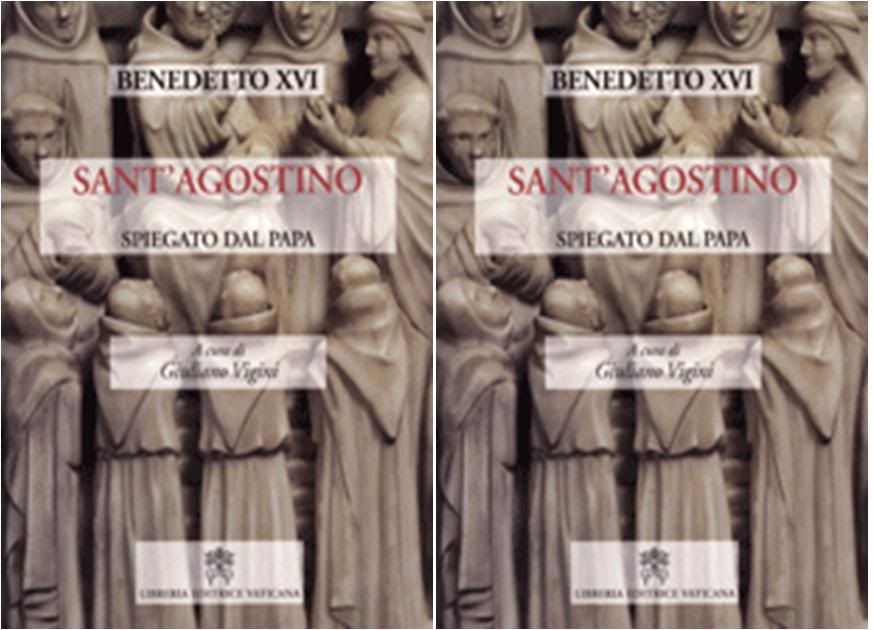

At the same time, the Vatican publishing house has come out with a collection of Benedict XVI's papal texts on St. Augustine, the figure who has most influenced his work as a theologian, which was reviewed earlier this month in Avvenire.

Augustine & Benedict:

Battling the heresies of today

by Giuliano Vigini

Translated from

January 12, 2009

Benedict XVI's frequent references to St. Augustine tells the story of a long friendship that started in Joseph Ratzinger's youth.

Cultivating and deepening his knowledge of Augustine's work, Joseph Ratzinger entered into full harmony with it, grasped its 'newness' and revelled in the enjoyment of a kindred spirit.

Augustine became the subject of his doctoral dissertation at the University of Munich in the academic year 1950-1951. This led young Prof. Fr. Ratzinger to inquire further and to understand in a fresh manner the sacramental nature of the Church, through the Christological and ecclesiological thinking elaborated by Augustine, in whose vision and action, nothing is separated, everything tends to interact and compose together a fruitful harmony.

In fact it is obvious that the doctrine of Augustine left a deep mark on the young Ratzinger.

In the courses, seminars and lectures that he gave in the theological faculties of four German universities - Bonn, Muenster, Tuebingen and Regensburg - from the late 1950s to 1977 when he was named Archbishop of Munich-Freising, Augustine was his constant point of reference - one of the inspirational bases for his theology as well as a spiritual lighthouse of his Magisterium.

For Benedict XVI, the turbulent course of Augustine's life and his eventual anchoring in the faith was characterized above all by a 'passion for the truth', as he recalled during the solemn Eucharistic concelebration in the Orti Borromaici (Borromeo Gardens) of Pavia when he came to pay homage to the remains of Augustine (April 22, 2007).

This was not truth understood as an abstract philosophical principle, but as a tangible reality - not a remote mirage, but an incarnated truth. In which it is faith that throws wide open the horizons for such truth, leading to that essential link between 'intelligere' (to understand) and 'credere' (to believe) in the context of reason and the authority of faith, faith as thought and faith as lived.

But first of all, there was the humility with which Augustine set out to open the doors to the mystery of God - the humility to which every Christian is called: "The humility of God's incarnation should match the humility of our faith," Augustine wrote, "which lays down all-knowing arrogance and bows down when it enters to become part of the community of the Body of Christ".

After his journey to conversion and coming home to the faith, Augustine proved his humility, the Pope underscored, in the sacrifice of his own dreams (above all, once he had become a priest, to devote himself to the contemplative life), to become a living Gospel among men. In the crossroads of life - when one chooses to go one way but God asks us to go the other - such humility is required.

Augustine had the humility, placing himself totally in the service of others: "Ever anew, to be there for everyone, not for one's own perfection; ever anew, to be with Christ, to give one's life so that others may find him, who is true Life".

Augustine's humble faith was shown even in his endless desire for God's mercy. His was not the attitude of someone who has received the gift of grace once and for all, but on the contrary, of someone who all his life considered himself to be 'a mendicant of God' (mendicus Dei) and therefore continued to seek him to obtain his pardon and help.

This aspect of Augustine also highlights the urge for 'permanent conversion' together with 'the grace of perseverance' which we must pray for daily to the Lord.

Finally, the passion for truth, which in Augustine finds its outlet in his faith in Christ and in the Church, is also expressed as a great passion for man. Faith does not close one's doors, it does not isolate, it does not abandon reason and freedom, it does not exclude anything.

Rather, faith opens up, expands, orients and leads, because faith in 'God Love' (1 Jn 4,8.16) is that which manifests itself as an expansion of love, and the Church is most herself to the degree that it is a community of love.

Benedict XVI's first encyclical,

Deus caritas est - which he symbolically gave to the world in front of Augustine's tomb - and which "owes very much to him" - is, in fact, a mirror of the commandment of charity, lived as service to truth and Christ's love.

In presenting Augustine, Benedict XVI arrives at the heart of his teaching, from which he has drawn the thoughts, words and examples that constitute the guidelines for his own Magisterium. Augustine is a mirror that reflects part of him.

In reviewing his theological, spiritual meditative and cultural works, one can truly grasp the Augustinian line that inspires and holds together his reflections.

There appear two be two cardinal concepts along which Benedict XVI develops his thought: truth and unity.

Truth understood as a 'symphony' according to an ancient concept revived and made famous by Hans Urs von Balthasar.

Unity understood as communion in the truth, where differences do not splinter into ruinous particularisms, but act as a bond in a reciprocity of love that always looks at the greater good, the truth - full, total and harmonious.

Absent these premises, the approach to truth becomes a 'mono-phony' rather than a 'sym-phony' - a solo rather than polyphony.

It is what Johann Moehler - one of the theologians most appreciated by Benedict XVI (along with Newman, Rosmini, Guardini, De Lubac, Congar, Von Balthasar...) - expressed in a similar way, speaking of the sense of superior beauty one gets from the sound of a polyphonic choir: not so much because they are singing impeccably, but because the training of the singers and the wisdom of their conductor are such as to blend together different voices and tonalities into one harmony.

Such is the work of Benedict XVI, who recalls in many ways the various aspects of Augustine's preaching and pastoral action.

Already in his celebrated

Rapporto sulla Fede [his interview-book with Vittorio Messori), the author faced a series of theological adn moral issues - from the concept of Church to the tragedy of morals; from liturgy to separated brothers; from the theology of liberation to feminism - making his points firmly and seeking to dissipate the numerous equivocations that have surrounded these issues.

Today, some of those questions have come back; some have changed form; and some have been added on, feeding old and new debates.

Indicating the sources of the faith and an authentic interpretation of texts, Benedict XVI always has the bar firmly centered, in which faithfulness to principles, to Tradition, to a clear and solid Christian identity, does not preclude the possibility of seeing and applying - in an intelligent and balanced way - whatever will serve to be able to live the faith ever more consciously, for the Church and for men.

If, in the time of Augustine, controversies were doctrinal in nature and his contemporaries saw the strenuous efforts of the Bishop of Hippo to combat so many heresies and deviations (Manichaean, Donatist, Pelagian, etc), today the great problems are of an ecclesial and pastoral nature, considered above all within the context of that vast subject of 'the new evangelization', in a world that is getting more secularized, within the Church as well as outside it.

All of Benedict XVI's commitment, in fulfillment of his own mandate to protect and confirm his brothers in the faith, is to remind the world of the need for a strong rootedness in Christ and the perennial values of Christianity.

These are the only true prerequisites for being Christians who are mature in living their faith and credible in bringing it to others.

That is why Benedict XVI does not tire - in the name of Augustine, who is one of the founding fathers of Western culture - to rally the faithful around the Christian foundations of Europe, which serve as the mortar holding together the idea of man himself as a sacred being because he is a creature of God and inviolable in his human and personal dignity.

Without such roots, not only will the Christian identity be lost which has spiritually and culturally shaped Europe, but the profound truth about man and his destiny will likewise be stripped away instead of being at the common heart of Europe itself today.

The TV movie stars Alessandro Preziosi as the young Augustine and Franco Nero as the older Augustine, with Monica Guerritore as St. Monica. After the special preview for him last September in Castel Gandolfo, the Pope greeted Ms. Guerritore.

Here is what the Holy Father said extemporaneously at the time:

At the end of this great spiritual voyage that is portrayed in the film that we just saw, I feel I must say Thank you to all those who have offered us this vision.

Thanks to Bavarian TV for its generous commitment - it is a great joy that a casual observation I made three years ago* started off a journey that has brought us this great representation of the life of St. Augustine. Thank you to Lux Vide and to RAI for this realization.

In fact, the film seems to be a spiritual voyage to a spiritual continent that is very remote from us, but also very near, because the human drama remains the same.

We have seen how, in a context that is very distant for us, all the reality of human life is portrayed, with all its problems, its sorrows, its failures, as well as the fact that, in the end, Truth is stronger than any obstacle and finds man.

Externally, the life of St. Augustine may be seem to end tragically: the world in which he lived and for which he lived, is ruined. But as the film affirms, his message has lived on, and even through the continuing changes in the world, that message endures, because it comes from the Truth and leads to Love, which is our common destination.

Thank you to everyone. Let us hope that many, upon seeing this human drama, may be found by the Truth and may, in turn, find Love.

Augustine: His life

is the stuff of epics

by Roberta De Monticelli

Translated from

January 28, 2010

Fiction is fiction and can touch extreme poles of invention. It can take you to the completely imagined house of Augustine but nonetheless full of action and emotion, as all fascinating fiction is, or to a probable Augustine who is nonetheless more plausible than a picture of plain truth, if as Aristotle says, poetic possibility inherently goes beyond true stories, which happen by accident, as it were.

The televiewer can judge, in this film on Augustine. I would like to indicate at least two aspects which make this man who lived more than 1600 years ago a partner in dialog for all of man’s contemporary doubts – certainly much more than most bishops living today.

Augustine, besides being the supreme Father of the Western Church, was also a bishop who had powers far different from that of a contemporary bishop. In that era of enormous geopolitical turmoil, of the collapse and rejection of all the structures of material and moral government in human society.

If Augustine the philosopher was great, detached from all violence, luminous in his questioning, serene in his reasoning, contemplative even in the passion of his research, Augustine the bishop was disconcerting! He persecuted heretics pitilessly.

His

Confessions embodies all the essentials of human life: childhood and adolescence, lust and love, mourning, friendship, ambition, intellectual inebriation, the torments of the soul; the journeys, roads and vities of the Roman empire; the elite and the common people; interior conflict, radical choice, the times itself, memories and God.

And yet, from the viewpoint of events and real action, nothing really happens before the first great turning point of his conversion and the brief spring of his new life, before he returns to his native Africa and takes on his ecclesial responsibilities.

But the last chapters of that autobiography, chapters we might describe as ‘pacified’, no events ‘happen’. at all but everything does in his theological and metaphysical thinking. In Books X-XIII of the

Confessions, he lays down all the foundations and supporting vaults of Western thought, or if you prefer, of European civilization and culture.

Definitely Christian, certainly. But it is precisely its surprising aspects – incredibly still so much ignored – of Augustinian theology and spirituality that we wish to remind the reader, aspects that respond so much to our contemporary doubts.

The first aspect is the sovereign freedom with which Augustine invites everyone to read and understand the Bible. "The mind is nourished only by that which makes it rejoice”, Augustine writes in Book XIII of

Confessions – the book that is dedicated to the Spirit.

Today, one must advise fundamentalists, not only American, who continue to perversely maintain a cosmogonic reading of the Bible, that Book XIII, the last of Augustine’s

Confessions, is an exegesis of Genesis which radically applies the principle of the spirit precisely where the letter (literalness) kills it. It is a spiritual exegesis, for which we can also use the terms symbolic and allegorical.

Creation is seen as a sensory offering - the world as it appears to the new man, the renewed or recreated man, the man reborn in the spirit. But the perspective that strikes us is that creation here is seen as ‘re-creation’, a rebirth of the spirit to the experience of things and men, in which every entity is seen as closer to its essence and recovers a ‘transcendent’ sense – one that goes beyond the obvious, or what is taken for granted – to every routine action, to every quotidian gesture. A process that takes place invisibly, beyond the worn-out words we use.

A great contemporary poet, Mario Luzo, would say of Augustine’s

Confessions: It shows us the world as at its nascent stage, with each thing situated “within the pullulating presence of their continuing origin".

This particular book of the

Confessions can be seen as a grand theory of inspiration. In the spirit, the power of memory and the actuality of experience are found in an ignition of love, the instant in which the living word is born. The ‘fruit’ of the spirit is thus the flowering – almost proliferation – of sensory images, the ‘forest of symbols’ in our life, whose text, Scriptures, becomes transformed in Augustine’s writing.

Dante would echo this theory of inspiration: “I am one who am the scribe of love; that, when he breathes, take up my pen, and write as he dictates."

The second aspect of Augustine’s relevance concern the most famous pages of the

Confessions: those about eternity and time. Time was born with the world – it is just one of its dimensions, as contemporary physicists believe. “There was never a time when there was no time”. Once more, one thinks of the American fundamentalists who have transformed the poetry of the seven days of Creation into a kind of primitive cosmogony.

But the solid and foursquare Thomas Aquinas, who knew his Augustine well, tells us that the when and how of space-time, whether they are finite or infinite, how they came to contain what they contain, is not pertinent at all to theology

[???], and that moreover, the novelty of scientific discoveries, their novelty compared to what is ordinarily perceptible, is just one of the aspects of the world seen as creation,

Then, there is another aspect of the renewed interest in Augustine.

Augustine: A saint for

the global era and the Internet

by Armando Torno

Translated from

January 28, 2010

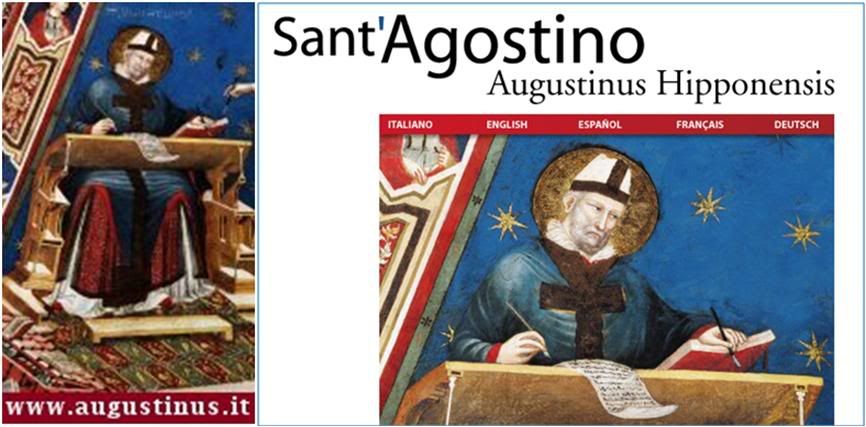

Augustine of Hippo comes to the small screen in Italy Sunday and Monday in two installaments – Benedict XVI previewed a synthesis of the two parts at the Vatican last autumn . But he iis already on the Net – all his writings.

www.augustinus.it/links/inglese/index.htm

www.augustinus.it/links/inglese/index.htm

The Italian publishing house Citta Nuova, which promoted the initative, recently completed online publication of Augustine texts in more than 70 volumes – it is now completing the indexes and Augustine’s references, to be followed by iconographic supplements and subsequent other enhancements. The texts comprise more than 50,000 pages; 80 Augustinian scholars worked on the compilation.

To give an idea of the project scope, it is as though Augustine had written

The Divine Comedy 100 times and Manzoni’s

I Promessi Sposi 300 times. In this ocean of culture and spirituality, Augustine’s famous

Confessions are ALMOST but a drop.

It is not exaggerated to believe that Augustine was the genius of Christianity. Almost every idea of the Church passed through his wRItings, and its ancient patrimony was all filtered through his pages.

It Is equally true that the saint’s immense work left traces in people like Heidegger and Einstein, inspired Luther and many Catholic reforms as well. Voltaire scrutinized him minutely in order to rebut him. Reading a page from Augustine prompted his remark: “Have you read the Pathers of the Church? Yes, but they will pay for it!”

Libertines have used the

Confessions as a model for better knowing themselves, as in a fascinating work by Laurence Tricoche-Rauline, Identité(s) libertine(s) (Honoré Champion, Paris 2009). The mystics venerated him. Popes have studied him, especially Benedict XVI.

A novelist like Julien Green said: “St. Augustine never disappoints... He is always ahead of any era in which he is read”. Karl Jaspers in his book

The great philosophers ranks him as one of the three creators of Western thought with Plato and Kant.

But to get back to Augustine online. To better focus this signal event, we spoke to Remo Piccolomini, editor of the Nuova Biblioteca Agostiniana [New Augustinian Library; Franco Monteverde, general editor of the volumes and author of the indexes; and Lorenzo Boccanera, electronic engineer and Webmaster of the site. At

www.augustinus.it one can choose to read Augustine in Italian, English, French, Spanish and German.

Two search engines allow navigation through the pages similar to Google’s for news items. Search mechanisms are constantly being improved and enhanced daily. In 2005 before the site was completed, it had 100,000 hits. This year, at least 3 million are expected. It must not be forgotten that until 1986, Citta Nuova was publishing Augustine’s works on paper.

If Lorenzo Boccanera considers his task to be the equivalent of a ‘modern scribe’, Franco Monteverde must read and reread the

Complete Works to construct his indexes, he had started this with the usual index cards as people did until about 20 years ago but now he has the benefit of advanced software to do it.

He has absolutely no doubts: “Augustine can explain the great truths of the faith even to illiterates. He always manages to surprise, even when you have reread him many times. He lovingly draws his reader to his thought, almost as if he were taking him by the hand”.

[In this, as in the content of the thought itself, his most illustrious contemporary follower has followed his model!]

Remo Piccolomini, who has inherited the great work done by Agostino Trapè — who founded Citta Nuova in 1954 and was one of the great scholars of Patristics [study of the Fathers of the Church] – believes that “Augustine is unlike any author. He had been everything – the young man who lived a brilliantly worldly life and the saint: he was a citizen of the world not a mere intellectual. He was truly ‘modern’ in that his pages continue to resound today with relevant ideas. Papini once said that he was one of those rare men who fail to die.”

It must be said that Citta Nuova’s enterprise has no equivalent. Spain’s BAC (Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos) has tried something simliar, but theirs have no supplements and indexes, no illustrations and iconography are planned, and the editorial effort cannot match the incredible authoritativeness of the Italian team.

The Citta Nuova online Augustine also offers helpful tips – such as identifying the topics most sought and those which require greater examination in depth for their actual relevance. One can organize a personal concordance to check out various points of interest that would never have been possible only with one’s memory, thus enabling a clarification of such points.

All this is important for theology, philosophy, history, literature and general culture – but not even the world of politics should make the mistake of ignoring it.

A Citta Nuova techie shows the features of Augustine online to the Holy Father.

A Citta Nuova techie shows the features of Augustine online to the Holy Father.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 01/02/2010 05:19]