Corriere della Sera published the text of Mons. Gaenswein's intervention at the book presentation last Friday.]

The pope emeritus and his outlook

Corriere della Sera published the text of Mons. Gaenswein's intervention at the book presentation last Friday.]

The pope emeritus and his outlook

on the West and on Europe

by Archbishop Georg Gaenswein

Translated from

May 12, 2018

Before he became Pope, Joseph Ratzinger thought of himself as a German, but perhaps even more, as a Bavarian. Yet because of his family origins, as a child, he always looked towards Salzburg in Austria, having before his eyes the culture of the House of Hapsburg, especially because his maternal grandmother came from the South Tyrol (which is now part of Italy).

Crossing frontiers has characterized his life, with the constnat background of Catholicity’s infinite horizon. Therefore, from childhood, his political homeland was represented not by frontiers but by the West in its entirety, even in the days when the furies unleashed by totalitarianism risked precipitating our continent into the abyss.

So it was not surprising that early on, Europe became the political passion of the young scholar Joseph Ratzinger. Nor that the young Ratzinger was fascinated by Konrad Adenauer and by the poltiical resolve with which Germany’s first postwar Chancellor resisted all the flatteries and promises offered by the Soviet Union after the ‘break in civilization’ that German experienced under National Socialism, to anchor the new Federal Republic of Germany to the system of values inherent in Judaeo-Christian history and that of the Latin West.

Uniquely in this this history – as Joseph Ratzinger recognized early on – the God of Jacob was recognized not as a God who rages but above all, a God who loves his creatures, who does not force man to do as he should but to win him over. Only in such a cultural space could the unmatchable ‘Cbristian freedom’ have been discovered, developed and defended - a freedom spoken about 1500 years ago by St Columban who was inspired in his missionary work by the knowledge that «S

i tollis libertatem, tollis dignitatem» - If you take away freedom, you take away dignity. Words that adorn the Chapel of St. Columban in the subterranean space of St. Peter’s Basilica, and the motto that guided that great 6th century Irish missionary.

In the Vatican grottoes under the papal altar, the Confessio that Bernini built over the tomb of the Prince of Apostles, the words of Columban have come to be an integral part of the foundations of the papacy itself.

It was the spirit in which the pilgrim Irish monks of the 6th century Christianized Western Europe, almost re-founding it in the midst of much internal migrations. A spirit that was persuasive to the young Joseph Ratzinger. And that is why the beautiful title of the book we are presenting today could almost be considered as a

cantus firmus [a fixed song] in the life of Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI.

The pope who came from Germany matured as a man, thinker and professor in the postwar ‘Catholic epoch: a time when Erich Przywara, mentor of Josef Pieper, conceived his book "The idea of Europe” and when Konrad Adenauer, Robert Schuman and Alcide de Gasperi took the risk of undertaking to re-found Europe from its ruins, recovering the legacy of the Carolingian West. It was at this time that the young

homo historicus Joseph Ratzinger, who was extremely educated and cultured early on, became a

homo politicus.

His most political idea even then coincided with the theological concept that was most important to the young priest: the truth, which much later he would use in the motto for his archbishop’s coat of arms, expressing his desire to win over co-workers for the truth.

“If we detach ourselves from the concept of truth, we detach ourselves from the foundation”, he told Pere Seewald in February 2000 while they were staying in Montecassino, mother house of the Benedictine monasteries. He continued:

“One of the most significant sayings of Jesus was about fire and peace ["I have come to set the earth on fire, and how I wish it were already blazing!... Do you think that I have come to establish peace on the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division” (Lk 12:49,51); In Matthew, his words are “I have come to bring not peace but the sword”] and it shows us today the conflict inherent in authentic peace – when truth is worth suffering and even conflict. It shows that one cannot accept lies for the sake of ‘living in peace’. No one has the courage these days to say that what the faith tells us is the truth”.

To seek the truth and fight for it thus became the thread running through the life of Joseph Ratzinger, later Benedict XVI. Because, of this he is convinced: it is a truth we cannot ‘have or possess’ but merely approach. Indeed, for the faith of Christians and according to their understanding of the truth, Truth is a person – in Jesus Christ, in whom God has shown us his face.

Because of this conviction, Ratzinger the theologian became an interlocutor particularly respected by Jurgen Habermas, the great German philosopher who has declared himself ‘devoid of religious ears’, but who agreed with Ratzinger that the Judaeo-Christian model of man created in the image and likeness of God determined the essential nucleus of Europe. From this ‘theologically founded secularity’ which Josef Piper said characterized the Western world, later the constitutionalist Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde drew the conclusion that «The secularized liberal state lives on assumptions that it is unable to guarantee”.

Believer and non-believer can come together ‘in doubt’ that each one has, in his own way, Ratzinger wrote 50 years ago in his

Introduction to Christianity. Yet in the cultural space of Europe, believer and non-believer can come together not just in doubt but also in truth, as the Habermas-Ratzinger dialog contained in this book demonstrates.

Because of this, Pope Benedict XVI wished to highlight the frontier of this unique cultural space with respect to all other

cultures as he did intrepidly on September 12, 2006, in his famous Regensburg Lecture. He showed how the decisive affirmation in the Byzantine emperor Manuel II Paleologue‘s argument against conversion by force was that which, arising precisely from the Christian concept of God, “not to act according to reason, not to act with Logos, is contrary to the nature of God”. And he concluded by saying that “It is to this great logos, to this vastness of reason, that we invite our interlocutors to a dialog of cultures”.

When, in his Preface to this book, Pope Francis underscores that these texts, together with his predecessor’s Opera omnia, “can help us to understand our present and to find a solid orientation for the future”, what came almost spontaneously to my mind were the incisive words Benedict XVI said in defense of natural law when he addressed the Parliament of the German Federal Republic on September 22, 2011 at the Reichstag in Berlin. Words with which I wish to conclude my brief intervention today:

“

‘Without justice – what else is the State but a great band of robbers?’, as Saint Augustine once said”, Benedict XVI told the German legislators, speaking as as the teacher and professor he always has been.

Benedict VI We Germans know from our own experience that these words are no empty spectre. We have seen how power became divorced from right, how power opposed right and crushed it, so that the State became an instrument for destroying right – a highly organized band of robbers, capable of threatening the whole world and driving it to the edge of the abyss.

To serve right and to fight against the dominion of wrong is and remains the fundamental task of the politician. At a moment in history when man has acquired previously inconceivable power, this task takes on a particular urgency. Man can destroy the world. He can manipulate himself. He can, so to speak, make human beings and he can deny them their humanity. How do we recognize what is right? How can we discern between good and evil, between what is truly right and what may appear right?

Even now, Solomon’s request remains the decisive issue facing politicians and politics today.

The request of the wise King Solomon to the God of Jacob – “Give your servant, therefore, a listening heart to judge your people and to distinguish between good and evil” (1 Kings 3,9) – remains operative for the tasks and the challenges that politicians are called on today to confront, because that ‘historic moment’ that the emeritus pope spoke about in Berlin six years ago, is running its course and not yet concluded.

I thank you for your attention.

Andrea Gagliarducci focuses on the hitherto unpublished letter of the Emeritus Pope that is a highlight of the new book, in which he commented on a 2014 book by his friend and onetime co-author Marcello Pera, the mathematician-philosopher who became President of the Italian Senate and is now senator-for-life, perhaps the most famous of Benedict XVI's 'devout atheist' admirers, Italian intellectuals who recognized in the German theologian a superior intellect that was recognized by many at the time as arguably the best and brightest mind in public life in our time (and remains so, for no new light has emerged to match him, much less, to eclipse him).

Benedict XVI’s hitherto unpublished essay:

God is key to understanding human rights

The final question, for Benedict XVI, is always God.

Can a state be built without God? And how much

can the state involve itself in the lives of its citizens?

by Andrea Gagliarducci

Vatican City, May 14, 2018 (CNA) - The Ratiznger Schuelerkreis, the circle of Joseph Ratzinger's former doctoral students who have met annually since 1977, will gather this year to discuss the theme “Church and State, Church and Society.” Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI selected the topic, as he does for the group every year.

This topic is intimately connected to the content of a recently published book, and above all to a letter – previously unpublished – contained in that book.

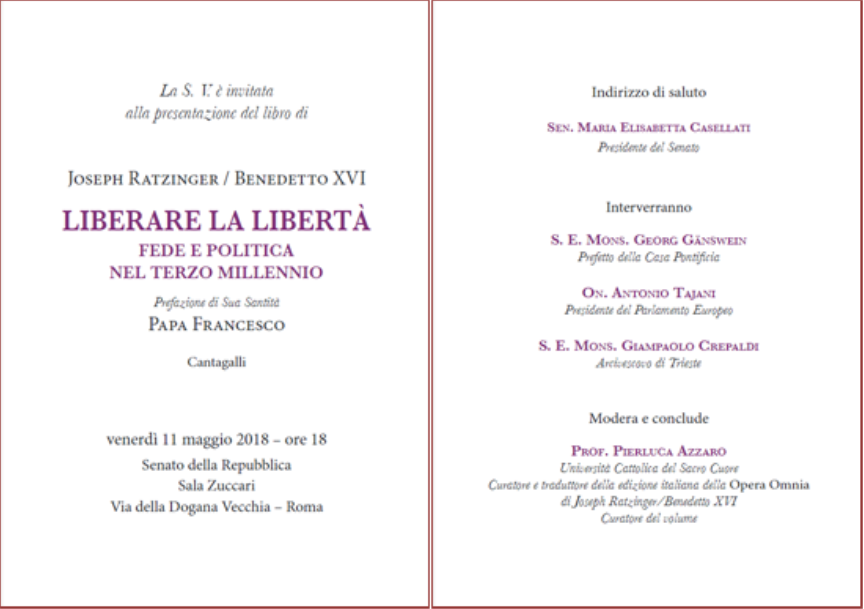

The book is

Liberare la libertà. Fede e Politica nel Terzo Millennio (Liberating freedom: Faith and politics in the Third Millennium), curated by professors Pierluca Azzaro and Carlos Granados, as the second of a series of 7 books of Joseph Ratzinger’s selected texts addressing the main themes of the pontificate. (An English-language edition of the book will be published later this year by Ignatius Press.)

Including excerpts from the second book of his JESUS OF NAZARETH TRILOGY, a dialogue Benedict XVI had with the German philosopher Jurgen Habermas in 2004, his address to the UK's political and intellectual elite in 2010, and his address to the German Bundestag in September 2011, the book provides a wide overview of Joseph Ratzinger’s political thought.

The final question, for Benedict XVI, is always God. Can a state be built without God? And how much can the state involve itself in the lives of its citizens?

The text, rather than being philosophical, is quite pragmatic. It deals with universal rights like the right to freedom of conscience, along with more general reflections on the idea of personal freedom.

The unpublished letter from Benedict XVI contained in the book provides a response to those questions, since it reaffirms “the centrality of the question of God.”

The letter was a response to a 2014 book by Italian philosopher and politician Marcello Pera, entitled

Diritti umani e cristianesimo. La Chiesa alla prova della modernità (Human Rights and Christianity: The Church put to the test by modernity”).

Benedict XVI’s letter makes immediately clear its point: despite the fact that Pope St. John XXIII’s encyclical

Pacem in Terris was significant for the use of human rights language in magisterial texts,

“the issue of human rights has practically acquired a place of great importance in the post-conciliar Magisterium and theology only with John Paul II”,]] Benedict XVI writes.

He notes that John Paul II’s emphasis on human rights was “the consequence of practical existence,” because

“in the idea of human rights is the concrete weapon capable of limiting the totalitarian character of the state,” offering room “for the freedom necessary not only for thinking of the individual person, but also, and above all, for the faith of Christian and for the rights of the Church.”

In John Paul II's view, human rights constituted “the rational force” that could countervail “the all-encompassing presumption, ideological and practical, of the state founded on Marxism” , and that an understanding of human rights could limit any absolutist claim by the state, even those founded on the basis of a religious justification (as most of the Islamic states are). Benedict wrote that this understanding was part of the contribution of John Paul II.

Christians have always demanded freedom of faith, in its early centuries, from a state – the Roman state – that “knew religious tolerance, but that affirmed an ultimate identification between state and divine authority to which Christians could not consent,” the pope emeritus wrote.

This is how the question of God erupts into history.

Christian faith, Benedict XVI noted, “necessarily included a fundamental limitation to the authority of the state, because of the rights and duties of the individual conscience”.

Although the idea of human rights “was not formulated this way,” it is not unjustified to Benedict XVI

“to define the duty of man’s obedience to God as a right, with respect to the state,” and so it is logical that St. John Paul II’s “should see human rights as preceding any state authority.”

Benedict XVI further said that man, made in the image of God, is a subject and not only an object of rights. Both of these statements are consistent with the philosopher Immanuel Kant description of man as an end and not as a means.

Kant is not invoked by chance, since he is the philosopher who inspired ideas central to the Enlightenment. Most of contemporary secular thought is rooted in Kant’s thought, but Benedict XVI’s letter showed that even Kant is to some extent in debt to Christian philosophy.

[I have always been in awe of Joseph Ratzinger's ample command of the history of ideas, and the clear linearity with which he presents it all - of which the encyclical Spe salvi is perhaps the prime example.]

From a historical perspective, the notion of human rights was born out of Christianity, Benedict argued.

The discovery of America led to a question: As the people of the New World were not baptized, did they have rights or not? Ultimately, that they were made in image of God was understood as the basis from which they derived rights.

It became clear that as children of God, unbaptized people “were already subjects of rights and therefore could claim respect for their humanity,” Benedict XVI noted.

Speaking of that conclusion, Benedict wrote that:

“It seems to me that ‘human rights’ have been recognized here, which precede the acceptance of the Christian faith and of any state power whatsoever.”

In addition, Benedict XVI explained, the first Christians had a particular attitude toward the Roman state. Because they were the first to believe in a universal religion, unbounded by national or ethnic identity, Christianity "redefined the essence of religion".

Christ's great commission "Go and make disciples of all nations", Benedict writes, “does not mean immediately demanding a change in the structure of individual societies,” but it rather demands “that all societies be given the possibility to welcome his message and live in accordance with it.”

Benedict XVI wrote that religion is not a “ritual and observance that ultimately guarantees the identity of the state,” but it is instead and precisely "recognition of the truth,” since the spirit of man “has been created for the truth.”

The pope emeritus underscored that “this connection between religion and truth includes a right to freedom that can licitly be considered as being in profound continuity with the authentic core of the doctrine of human rights, as John Paul II evidently did.”

Benedict XVI also warned of the danger in any vision that sees the “natural order” of society as “a complete totality in itself and does not need the Gospel.”

For all of those reasons, Benedict XVI said that “everything rests on the concept of God,” because “someone who speaks to his creatures and shows human beings what he wants of them."

Hence, Benedict's conclusion that “the idea of human rights ultimately retains its solidity only if it is anchored to faith in God the creator, from whom it receives the definition of its limitation and at the same time its justification.”

“The concept of God,” Benedict XVI noted “includes the fundamental concept of man as a subject of law, and thereby justifies and at the same time establishes the limits of the conception of human rights.”

In the end, the question of God is strictly connected with the issue of truth.

Archbishop Georg Gaenswein, Prefect of the Pontifical Household and Benedict XVI’s personal secretary, noted May 11 that

Benedict XVI’s political approach “coincides with the most important theological notion to him already as young priest: the truth.”

“Seeking truth, and struggling for it, has been the red thread in the life of Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI. He is convinced of this: that truth cannot be possessed; one can only approach truth, since, according to the faith of Christians and in accordance with our understanding of truth, the truth has become a person in Jesus Christ, in which God has shown his face.”

God becomes, therefore, central to every political question, even when God is denied.

In the book’s foreword, Pope Francis wrote that a state would be “false and anti-Christian” if it understood itself to be “the ‘whole’ of human hopes and possibilities.” Such a totalitarian and tyrannic lie, he wrote becomes “demonic and tyrannic.”

Pope Francis elaborated: “On this basis, along side St. John Paul II, Ratzinger elaborates and propose a Christian vision of human rights able to question, on both practical and theoretical levels, the totalitarian claim of the Marxist state and of the atheistic theology on which it was founded.”

In the end, there cannot be any state without God, because no institution can hold without truth: this is the lesson of Benedict XVI’s political vision.[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 16/05/2018 02:30]