Just a bit of chronological context: 'INTRODUCTION TO CHRISTIANITY', which became an almost-instant theological classic, was published one year before Jorge Bergoglio was ordained a priest.

Just a bit of chronological context: 'INTRODUCTION TO CHRISTIANITY', which became an almost-instant theological classic, was published one year before Jorge Bergoglio was ordained a priest.

ALWAYS AND EVER OUR MOST BELOVED BENEDICTUS XVI

Hitherto unpublished essay in new book

Hitherto unpublished essay in new book

is vintage Ratzinger grand cru

even in his Emeritus years

May 9, 2018

The book will go on sale May 10, but Settimo Cielo is previewing here its most anticipated pages: a text by Joseph Ratzinger that bears the date of September 29, 2014, and has never been published until now, on the capital question of the foundation of human rights, which, he writes, are either anchored in faith in God the creator, or do not exist.

It is a text of crystalline clarity, which Ratzinger wrote in his retirement at the Vatican one and a half years after his resignation as pope, in commenting on a book - published in 2015 under the definitive title

"Diritti umani e cristianesimo. La Chiesa alla prova delle modernità" (Human rights and Christianity. The Church put to the test of modernity) - by his friend Marcello Pera, a philosopher of the liberal school and a former president of the Italian senate.

In his commentary, the Emeritus Pope analyzes the irruption of human rights in the secular and Christian thought of the second half of the twentieth century, as an alternative to the totalitarian dictatorships of every kind, atheist or Islamic. And he explains why “in my preaching and my writings I have always affirmed the centrality of the questions of God.”

The reason is precisely that of guaranteeing that human rights have their foundation of truth, without which rights are multiplied but also self-destruct and man ends up negating himself.

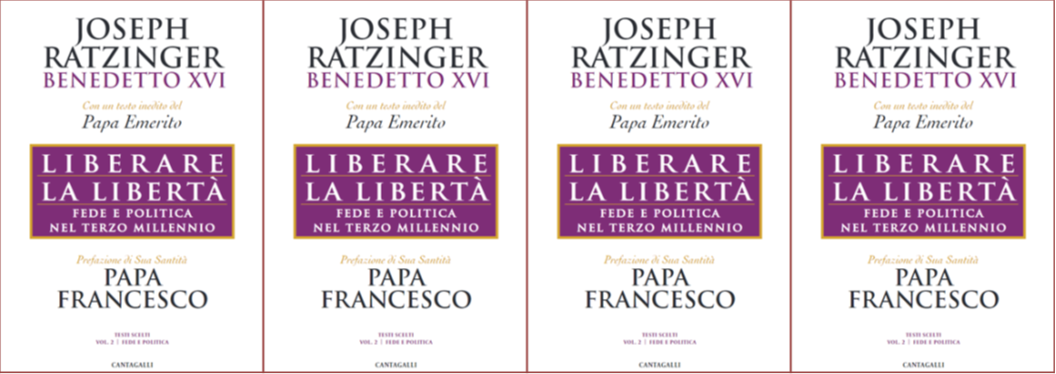

The volume in which this composition is about to come out, together with other texts by Ratzinger on the connection between faith and politics, is published in Italy by Cantagalli: Joseph Ratzinger-Benedict XVI,

Liberare la libertà. Fede e politica nel terzo millennio, edited by Pierluca Azzaro and Carlos Granados, preface by Pope Francis, Cantagalli, Siena, 2018, pp. 208, 18 euro.

It is the second in a series of seven volumes entitled “Joseph Ratzinger - Selected Texts,” on the fundamental themes of Ratzinger’s thought as theologian, bishop, and pope, published contemporaneously in multiple languages and in various countries: in Germany by Herder, in Spain by BAC, in France by Parole et Silence, in Poland by KUL, in the United States by Ignatius Press.

Both volumes issued so far have a preface by Pope Francis.

And here is the previously unpublished text that opens the second volume of the series. The subtitle is the original, by Ratzinger himself.

IF GOD DOES NOT EXIST, HUMAN RIGHTS COLLAPSE

Elements for a discussion of the book by Marcello Pera

"The Church, human rights, and estrangement from God"

by Joseph Ratzinger

The book undoubtedly represents a great challenge for contemporary thought, and also, in particular, for the Church and theology. The discontinuity between the statements of the popes of the nineteenth century and the new vision that begins with Pacem in Terris is evident and on it there has been much discussion. It is also at the heart of the opposition of Lefèbvre and his followers against the Council. I do not feel able to give a clear answer to the issues of your book; I can only make a few notes which, in my view, could be important for further discussion.

1. Only thanks to your book has it become clear to me to what extent a new course begins with Pacem in Terris. I was aware of how powerful the effect of that encyclical on Italian politics had been: it gave the decisive impulse for the opening up of Christian Democracy to the left.

I was not aware, however, of what a new beginning this represented also in relation to the conceptual foundations of that party. And yet, as far as I remember, the issue of human rights actually acquired a place of great significance in the Magisterium and in postconciliar theology only with John Paul II.

I have the impression that, in the Saintly Pope, this was not so much the result of reflection (although this was not lacking in him) as the consequence of practical experience. Against the totalitarian claim of the Marxist state and the ideology on which it was based, he saw in the idea of human rights the concrete weapon capable of limiting the totalitarian character of the state, thus offering the room for freedom necessary not only for the thinking of the individual person, but also and above all for the faith of Christians and for the rights of the Church.

The secular image of human rights, according to the formulation given to them in 1948, evidently appeared to him as the rational force contrasting the all-encompassing presumption, ideological and practical, of the state founded on Marxism. And so, as pope, he affirmed the recognition of human rights as a force acknowledged throughout the world by universal reason against dictatorships of every kind.

This affirmation now concerned not only the atheist dictatorships, but also the states founded on the basis of a religious justification, which we find above all in the Islamic world. The fusion of politics and religion in Islam, which necessarily limits the freedom of other religions, and therefore also that of Christians, is opposed to the freedom of faith, which to a certain extent also considers the secular state as the right form of state, in which that freedom of faith which Christians demanded from the beginning finds room.

In this, John Paul II knew that he was in profound continuity with the nascent Church which was facing a state that knew religious tolerance, of course, but that affirmed an ultimate identification between state and divine authority to which Christians could not consent. The Christian faith, which proclaimed a universal religion for all men, necessarily included a fundamental limitation of the authority of the state because of the rights and duties of the individual conscience.

The idea of human rights was not formulated in this way. It was rather a question of setting man's obedience to God as a limit on obedience to the state. However, it does not seem unjustified to me to define the duty of man's obedience to God as a right with respect to the state. And in this regard it was entirely logical that John Paul II, in the Christian relativization of the state in favor of the freedom of obedience to God, should see human rights as coming before any state authority.

I believe that in this sense the pope could certainly have affirmed a profound continuity between the basic idea of human rights and the Christian tradition, even if, of course, the respective instruments, linguistic and conceptual, turn out to be very distant from each other.

2. In my opinion, in the doctrine of man as made in the image of God there is fundamentally contained what Kant affirms when he defines man as an end and not as a means. It could also be said that it contains the idea that man is a subject and not only an object of rights. This constitutive element of the idea of human rights is clearly expressed, it seems to me, in Genesis: "I will require a reckoning of the life of man from man, from everyone for his brother. He who sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for in the image of God has man been made” (Gen 9:5f).

Being created in the image of God includes the fact that man's life is placed under the special protection of God, the fact that man, with respect to human laws, is the owner of a right established by God himself.

This concept acquired fundamental importance at the beginning of the modern age with the discovery of America. All the new peoples we came across were not baptized, and so the question arose whether they had rights or not. According to the dominant opinion they became genuine subjects of rights only with baptism.

The recognition that they were in the image of God by virtue of creation - and that they remained so even after original sin - meant that even before baptism they were already subjects of rights and therefore could claim respect for their humanity. It seems to me that here was a recognition of "human rights" that precede adherence to the Christian faith and any state power, whatever its specific nature may be.

If I am not mistaken, John Paul II understood his effort for human rights in continuity with the attitude that the ancient Church had toward the Roman state. In effect, the Lord's mandate to make disciples of all peoples had created a new situation in the relationship between religion and the state. Until then there had been no religion with a claim to universality. Religion was an essential part of the identity of each society. Jesus's mandate does not mean immediately demanding a change in the structure of individual societies. And yet it demands that all societies be given the possibility to welcome his message and live in accordance with it.

What follows from this in the first place is a new definition above all of the nature of religion: this is not a ritual and observance that ultimately guarantees the identity of the state. It is instead recognition (faith), and precisely recognition of the truth.

Since the spirit of man has been created for the truth, it is clear that the truth is binding, not in the sense of a positivistic ethics of duty, but rather on the basis of the nature of truth itself, which, precisely in this way, makes man free. This connection between religion and truth includes a right to freedom that can licitly be considered as being in profound continuity with the authentic core of the doctrine of human rights, as John Paul II evidently did.

3. You have rightly considered the Augustinian idea of the state and of history as fundamental, placing it as the basis of your vision of the Christian doctrine of the state. And yet the Aristotelian view may have deserved even greater consideration.

As far as I can judge, it had little importance in the tradition of the Church of the Middle Ages, all the more so after it was taken up by Marsilius of Padua in opposition to the magisterium of the Church. Afterward it was taken up more and more, beginning in the nineteenth century when the social doctrine of the Church was being developed.

One now began from a twofold order, the ordo naturalis and the ordo supernaturalis; where the ordo naturalis was considered complete in itself. It was expressly emphasized that the ordo supernaturalis was a free addition, signifying pure grace that cannot be claimed on the basis of the ordo naturalis.

With the construction of an ordo naturalis that can be grasped in a purely rational manner, an attempt was made to acquire an argumentational basis through which the Church could assert its ethical positions in political debate on the basis of pure rationality.

Correctly, in this view, there is the fact that even after original sin the order of creation, in spite of being injured, has not been completely destroyed. To assert that which is authentically human where it is not possible to affirm the claim of faith is in itself a correct position. It corresponds to the autonomy of the sphere of creation and to the essential freedom of faith. In this sense, an in-depth view is justified, indeed necessary, from the point of view of the theology of creation, of the ordo naturalis in connection with the Aristotelian doctrine of the state. But there are also dangers:

a) It is very easy to forget the reality of original sin and arrive at naive forms of optimism that do not do justice to reality.

b) If the ordo naturalis is seen as a complete totality in itself and does not need the gospel, there exists the danger that what is properly Christian may seem to be a superstructure that is ultimately superfluous, superimposed on the naturally human.

In effect I remember that once I was presented with a draft of a document in which at the end some very pious formulas were expressed, and yet throughout the whole argumentational process not only did Jesus Christ and his gospel not appear, but even God did not, and they therefore seemed superfluous.

Evidently it was believed it was possible to construct a purely rational order of nature which, however, is not strictly rational and which, on the other hand, threatens to relegate that which is properly Christian to the realm of mere sentiment. The limitation of the attempt to devise a self-contained and self-sufficient ordo naturalis emerges clearly here. Father de Lubac, in his "Surnaturel,” tried to show that Saint Thomas Aquinas himself - who was also referred to in the formulation of that attempt - did not really intend this.

c) One fundamental problem of such an attempt consists in the fact that in forgetting the doctrine of original sin there arises a naive confidence in reason that does not perceive the actual complexity of rational knowledge in the ethical field.

The drama of the dispute over natural law clearly shows that metaphysical rationality, which in this context is presupposed, is not immediately evident. It seems to me that Kelsen is ultimately right when he says that deriving a duty from being is reasonable only if Someone has placed a duty in being. To him, however, this thesis is not worthy of discussion.

It seems to me, therefore, that in the end everything rests on the concept of God. If God exists, if there is a creator, then being can also speak of him and indicate a duty to man. Otherwise, the ethos is ultimately reduced to pragmatism. This is why in my preaching and in my writings I have always affirmed the centrality of the question of God.

It seems to me that this is the point at which the vision of your book and my thought fundamentally converge. The idea of human rights ultimately retains its solidity only if it is anchored to faith in God the creator. It is from here that it receives the definition of its limitation and at the same time its justification.

4. I have the impression that in your previous book, Why We Must Call Ourselves Christians, you evaluate the great liberals’ idea of God in a way different than you do in your new work. In the latter it appears as a step toward the loss of faith in God.

On the contrary, in your first book you, in my opinion, had convincingly shown that without the idea of God European liberalism is incomprehensible and illogical. For the fathers of liberalism, God was still the foundation of their vision of the world and of man, so that, in that book, the logic of liberalism makes the confession of the God of the Christian faith necessary.

I understand that both assessments are justified: on the one hand, in liberalism the idea of God detaches itself from its biblical foundations, thus slowly losing its concrete strength; on the other, for the great liberals, God is and remains indispensable. It is possible to accentuate one or the other aspect of the process. I believe it is necessary to mention both. But the vision contained in your first book remains indispensable for me: that is to say, that liberalism, if it excludes God, loses its own foundation.

5. The idea of God includes the fundamental concept of man as a subject of law and thereby justifies and at the same time establishes the limits of the conception of human rights.

In your book you have shown in a persuasive and compelling way what happens when the concept of human rights is split from the idea of God. The multiplication of rights ultimately leads to the destruction of the idea of right and necessarily leads to the nihilistic "right" of man to negate himself: abortion, suicide, the production of man as a thing become rights of man that at the same time negate him.

Thus, in your book it emerges in a convincing manner that the idea of human rights as separated from the idea of God ultimately leads not only to the marginalization of Christianity, but also to its negation. This, which seems to me to be the true purpose of your book, is of great significance in the face of the current spiritual development of the West which is increasingly denying its Christian foundations and turning against them.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 10/05/2018 11:59]