Cardinal Biffi, along with Cardinals Meisner and Caffarra, are among the recently deceased cardinals who were most ‘in tune’ with Joseph

Cardinal Biffi, along with Cardinals Meisner and Caffarra, are among the recently deceased cardinals who were most ‘in tune’ with Joseph

Ratzinger/Benedict XVI, theologically, intellectually and pastorally, and and I am very glad that Aldo Maria Valli shares with us this preview

of a new book from him…

Not surprisingly, Valli mines a most relevant and precious reflection that he focuses on – Biffi’s denunciation of ambiguity in the Church and of

the widespread misuse of the word ‘pastoral’, even if Biffi wrote this in 1975… Trust Valli to get in his digs at Bergoglianism, even if indirectly…

When Giacomo Biffi, in his parish assignments after

years of teaching theology, fought for the Truth

Translated from

October 31, 2017

“I had never been to Legnano, not even incidentally”. Thus wrote don Giacomo Biffi, 32, in 1960, at the start of a new experience that would change his life. No longer professor of theology at the seminary of Venegono, but a parish priest in Legnano, at the parish of Santi Martiri (Holy Martyrs), where he would serve till 1969.

[Legnano is a small town at the northwestern extreme of the metropolitan area of Milan.]

Just looking at the dates makes clear the times we are referring to: Vatican-II, the youth protests everywhere, 1968 and its overnight cultural revolution, tensions within the Church herself, the birth of a strategy for just such tension, and the massacre in Piazza Fontana.

[Terrorist attack on Dec. 12, 1969, when a bomb exploded at the headquarters of Italy’s national farmers’ bank in Milan, killing 17 people and wounding 88. The same afternoon, three more bombs were detonated in Rome and Milan, and another was found unexploded. An Italian neo-fascist group was eventually found responsible for these incidents, which took place the year before the leftwing paramilitary Red Brigades began a string of numerous violent incidents in Italy, including assassinations, kidnapping and robberies that would last through the 1970s.]

For a priest, who had not before thought of himself as a pastor of souls but as a teacher, it meant getting into the eye of the tempest. But he never lost his spirit, and, along with other undeniable problems, he managed to see the positive aspects of the situation, from the viewpoint of the simple faith embodied by the people he served.

In 1969, he was transferred to central Milan itself, to the parish of Sant’Andrea, where he would serve till 1975. From a little town to the heart of the metropolis, from a peripheral parish to a historic Ambrosian parish whose church had been consecrated by the great Cardinal Ferrari

[Archbishop of Milan from 1894 to 1921].

Even in this case, look at the dates to understand the context in which don Giacomo had to lead his flock. He referred to that time as ‘the uneasy years’. And they were, far beyond what was expected. As he describes it:

"The ideological, moral, ecclesiastical, and social upheaval of those years - unprecedented in the history of Milan and Italy - came unexpected, at least for me. I think it was also unexpected for those who belonged to the ‘reassuring’ school of John XXIII, and were of the same mind even after the Council, who had become ‘specialized’ in reading with nonchalance the so-called ‘signs of the times’.”

Yes, everything seemed to be changing in those years, and the disorientation was great, even in the Church. The dominant word was ‘protest’. Protest against the priest, against the bishop, against the pope (Paul VI, who was Archbishop of Milan when he was elected pope). Protest too against traditional theology.

The other dominant word was ‘crisis’. It was a time when there were no longer any certainties, when there no longer seemed to be any secure foundations.

Don Giacomo, who never lost his indulgence for irony, fought to fight all that without coarseness. When a young man, “who was particularly inflamced and intemperate”, ferociously attacked Archbishop Giovanni Colombo, Biffi said to him: “Instead of deploring and getting indignant over the fact that there are bishops who you think are asses, why don’t you praise the Lord and rejoice that there are no asses who are bishops? God is great and involves all of us in his plan for salvation”.

But don Giacomo was deeply concerned, and using wit in the face of the devastation in the Church, does little. He himself acknowledged that pungent expressions and ironic phrases served nothing while everything seemed to be collapsing around you.

It meant one had to go out into the open in defense of the bishop, of the pope, of the unity of the Church. And he did so every day, as a combatant who does not accept the dominant demagogy nor acritical adherence to the dominant thinking.

With Jacques Maritain, he recognized that the modernism that was a threat to the Church at the start of the 20th century was nothing but the common cold compared to the contagious fever that became widespread in the Church of the 1970s and 1980s.

Then, another turning-point for Biffi. In 1975, Paul VI named him auxiliary bishop of Milan. A new experience began, a new life that lasted nine years until in 1984, John Paul II made him Archbishop of Bologna, and in 1985, a cardinal.

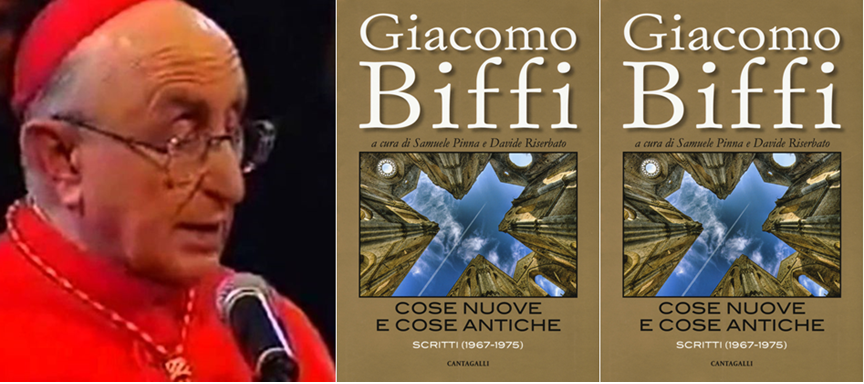

The don Giacomo I have been describing is, of course, Cardinal Giacomo Biffi, who died in Bologna in 2015, at the age of 87, and the bits and pieces I have described come from a beautiful new book,

Cose nuove e cose antiche. Scritti 1967-1975 (New things and old things: Writings from 1967-1975) on the less-known years of his human experience, spiritual and pastoral, those that he lived in Legnano and Milan as a parish priest.

The book, published by Cantagalli, and edited by Samuele Pinna and Davide Riserbato, carries an introduction by Monsignor Dario Edoardo Viganò (prefect of the new Dicastery for Communications) and is in every way a historical text. History seen from below, from the perspective of daily life. And it is valuable for understanding how the Church was before Vatican-II, how it was 'changed' by Vatican-II, and the upheavals it went through.

Biffi, who wrote best-sellers like «

Contro Maestro Ciliegia», «

Peppone, Pinocchio, l’Anticristo e altre divagazioni», «

Il quinto evangelo» and

«Memorie e digressioni di un italiano cardinale», writes very well, with unfailing clarity.

There are so many points for reflection offered by his memoirs as a parish priest, but I will concentrate on a word to which the cardinal dedicates particular attention. It is a word that at present is a major adjective in Church language: ‘pastoral’.

In a chapter entitled «Meditazione sull’aggettivo ‘pastorale’», Biffi starts out from a premise whose actuality struck me very much. He wrote:

“We live in an ecclesial era profoundly marked by ambiguity. The terms ‘church’, ‘faith’, ‘love’, ’prayer’, ‘priesthood’, ‘the world’, ‘dialog’, etc are not used by all Christians in the same sense”.

He wrote this in 1974, towards the end of his experience as a parish priest in Milan. Shaken violently by the diverse inerpretations of Vatican-II and by the social and political tensions that inevitably involved her, the Church was more than ever divided, and the future bishop and cardinal calls attention rightly to the language in use, which was both the instrument and the outcome of that division.

Always inclined to see what is good even in situations that appear most desperate,

Biffi asks whether ambiguity is the price one must pay – a form of evangelical charity – in order to continue saying we are all members of the same Church, without coming to any dramatic separations.

Nonetheless, noting that ambiguity can be found not just within the ecclesial organism that is the Church but “in a person’s very behavior, his writings, his discourse”, he denounces what he calls “a widespread horror of certainties” to the point that it has now become obligatory to present oneself to the world not with answers, but rather ‘shrouded in problems and accompanied by more questions”.

More than 40 years have passed, during which

ambiguity has now penetrated into the highest circles of Church leadership - facilely cultivated every time persons in authority, acting according to political and not evangelical criteria, seek to please the world, detaching mercy and charity from their essential and necessary link with truth.

“I believe,” Biffi wrote, “ambiguity is not a value, that charity should always arise from the truth and be constantly fed by it”.

And one of the words most prone to ambiguous use is, precisely, ‘pastoral’

[the apparent be-all and end-all justification for anything in the church of Bergoglio, so over-used at every turn that it has lost meaning, or rather, it can mean anything the user wants it to mean], and Biffi is surgically sharp in his critical look at the image of a pastor.

It is an image, he says, that in Scriptures and in the life of the Church, undergoes progressive slippage.

The pastor, or shepherd, is certainly God, and then Jesus, and then the Twelve Apostles, and later, priests. The pastoral task therefore widens according to co-responsibility, which means that no one can consider himself pastor by himself, but that all those who are called pastors simpy reflect the pastorality of Christ and the Father.

The point is that pastoral ministry “absolutely does not come from the flock, but that it constitutionally comes from above. Its legitimacy does not originate from below [i.e., those for whom a pastor is responsible] but from authority, and therefore from the truth of which such an authority is a repository and guardian. It follows that whoever exercises pastoral authority should verify daily his conformity not with his base, not with the people, but with the Chief Pastor.

Here, Biffi introduces another reflection that overturns all dominant stereotypes. It is often said that the Church lacks pastors, but

“among the serious problems of Christianity today, there is not just a shortage of pastors, but ther is also – and this, more dramatically - a lack of persons who recognize themselves as sheep in the evangelical sense”.

Pastoral action has one goal only: not consolation, not giving comfort, but eternal salvation. Pastoral action is pastoral only when its point of reference is Jesus. And Jesus proposes a decisive move that no one can bypass to obtain salvation: that is metanoia, or conversion. If it is true that no human problem can be alien to pastoral attention, it is just as true that the answer to human problems is conversion to the way of life preached by Christ.

There are so many passages that need to be cited. I will limit myself now to Biffi’s conclusion in his chapter on what is ‘pastoral’: “This reflection of ours has led us to identify some principles which seem to me irrenuncible. Of course, the difficulty starts when one truly wishes to incarnate these principles on an operative level.

But in these times, it would be a great thing already if we could all agree with each other about these principles”.

How true! The times being what they are.

[Modificato da TERESA BENEDETTA 05/11/2017 00:40]